In this episode, I interview Taylor Patrick O'Neill, a professor at Thomas Aquinas College’s New England campus and a co-founder of the Sacra Doctrina Project, a community of theologians hoping to revive the traditional speculative and sapiential dimensions of Catholic theology. In our conversation, we talked about the Sacra Doctrina Project and its mission, but we also discussed the 20th-century debate between Thomists and the ressourcement movement, the state of academic theology today, the appeal of universalism, and O’Neill’s work on the doctrine of predestination.

Interview date: October 30, 2024

The Window Light Podcast is a feature of Window Light, the newsletter for expert analysis on the fields of Catholic theology and ministry, explorations of historical theology, commentary on current events, and theological and spiritual reflections. The podcast features interviews with scholars and practitioners in the fields of theology and ministry. Be sure to subscribe to the Window Light newsletter for regular posts and other features!

Transcript

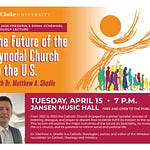

MATTHEW SHADLE: Hello, this is Matthew Shadle and you're listening to the Window Light podcast. In this episode, I'm talking to Taylor Patrick O'Neill, a professor at Thomas Aquinas College's New England campus and a co-founder of the Sacra Doctrina Project, a community of theologians seeking to recover the traditional speculative and sapiential character of theology. In the interview, we discussed the Sacra Doctrine Project and its mission, but also had a wide-ranging conversation about the 20th-century debate between Thomists and the ressourcement movement, the state of academic theology today, the appeal of universalism, and O’Neill’s own work on the doctrine of predestination, among other things. I really enjoyed our conversation, and I hope you do, too.

Hello, this is Matthew Shadle with the Window Light podcast, and today I'm with Taylor Patrick O'Neill, who is a professor at Thomas Aquinas College at their New England campus. Before that, he was a professor of theology at Mount Mercy University here in Iowa. He is the author of Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: A Thomistic Analysis,1 which we'll talk about a little bit at the end. But he's also one of the co-founders of the Sacra Doctrina Project, which is what I want to spend most of our time talking about So, welcome, Taylor.

TAYLOR PATRICK O'NEILL: Yeah. Thank you so much for having me on.

SHADLE: Alright, so I kind of introduced your career, but, you know, tell us a little bit more about yourself.

O'NEILL: Yeah. So, this is my fourth year being at Thomas Aquinas College. As you mentioned, I was at Mount Mercy University before that, in Cedar Rapids, and I was there for four years, as well. So, that was great. I really . . . I loved Iowa, and I miss many things about Iowa. Yeah, I did my PhD at Ave Maria University. I did a master's at CUA,2 so I've kind of been all over the place and have bounced around a bit, so.

SHADLE: Yeah. Wow. Alright, very good. And so Thomas Aquinas, their main campus is in California. But you teach at the New England campus, which is in Massachusetts, right?

O'NEILL: That's right.

SHADLE: So, just for my knowledge, are the two campuses similar, like they offer similar programs, or are there some differences?

O'NEILL: Yeah. So, the two campuses are, they're the . . . the curriculum is exactly the same. The way Thomas Aquinas College works is that there's a fixed curriculum. So, essentially every student gets the same degree. There aren't majors or minors or anything. So, the degree is technically a degree in liberal arts, but what it transfers as in transcripts is basically a Bachelor of Arts with a double major in theology and philosophy. So, it's a theology and philosophy heavy program with a fixed curriculum. And it's the same curriculum on the West Coast as the East Coast. They're really sort of two campuses doing the same thing.

SHADLE: Alright, just to serve more students geographically.

O'NEILL: That's right. Yep, that's right.

SHADLE: And so, then, what is your role there as an instructor? How does that work if there's no departments and majors?

O'NEILL: Yeah, that's another good question. So yeah, we don't have departments. So that means that the professors at the college are called tutors. They teach around the curriculum. So, I . . . My background being theology, I have taught a lot of theology while I've been here, but I'm also teaching other courses. So, I'm teaching a class this year on Aristotle's Physics and Aristotle's De Anima, a philosophy class. I've taught Latin. I've taught Euclid's geometry, philosophy of quantity is sort of what the course is. So, most of it is very philosophically oriented. So, we . . . But we do have, you know, mathematics, natural science. And they're, again, they're very philosophically heavy, but everyone does teach around the curriculum. So, I'm not in a particular department, as you mentioned.

SHADLE: Yeah. And that's, you know, teaching all those subjects, that’s the liberal arts for you. So, even at a more typical small liberal arts college, I taught not only theology, but also Plato, and even a smidge of modern Indian history. You never know what you're going to teach.

O'NEILL: Yeah, exactly. And when I was at Mount Mercy, I mean, yeah, I was in the theology department, but I taught philosophy courses, and I taught introduction to world religions, which was sort of an anthropology course. Yeah, I mean, that's just the gig these days with, you know, teaching appointments. You're usually expected to be a generalist and be able to teach a lot of different students different courses.

SHADLE: So alright, so I got to ask though, do you . . . If you had to pick, do you prefer Iowa or New England? You said you missed a lot of things about Iowa, but . . .

O'NEILL: Yeah. That's a . . . Oh, that's a difficult question.

SHADLE: Oh, sure. It's not a fair question either.

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So, I love the Midwest. I’m from the Midwest. I'm not from Iowa, but I'm from northeastern Wisconsin, so I miss the Midwest.

SHADLE: Okay.

O’NEILL: If the choice is between the Midwest and New England, I choose the Midwest. I do really like New England, though. I mean, it's very similar to the Midwest in some ways, especially where I'm at is sort of western Mass. So, it's more rural, so a slower pace like the Midwest, and it's, I mean, it's beautiful, especially in the fall. I mean, you can't beat New England in the fall. The hills, the trees. It's . . . Honestly, I think New England in the fall is one of the most beautiful places in the country, at least that I've seen. It's hard to beat that.

SHADLE: I was thinking about this earlier today. One thing Iowa has going for it, at least compared to other places in the Midwest anyway, that people may not realize is there are just so many communities of vowed religious here.

O’NEILL: Mm hmm.

SHADLE: We have, like, many religious sisters, you have the Trappists, you know, and the Trappistines. So, all kinds of . . . and that's just in the northeast part. So, Iowa has a lot of religious, has that kind of Catholic vibe to it, even if it’s not a majority Catholic area at all.

O'NEILL: Yeah, I think that's right. And even the neighboring areas. I mean Indiana, Illinois, they also have so many communities. I definitely think New England is less Catholic, and that's very noticeable. You know, even all these years later, after, New England was settled by Puritans, there's definitely still a cultural difference.

SHADLE: Yeah, I mean, Boston, for example, I might . . . You might make a case . . .

O'NEILL: Boston, I think, is different, is very Irish Catholic. I think that's definitely true. But yeah, when you get into rural New England, it's very, yeah . . .

SHADLE: Yeah, that's for sure. Okay, let's get to it. So, I mentioned that you are a co-founder of the Sacra Doctrina Project. So, what is that, and why . . . why was that established?

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, it's a good question, what it is. It's hard to explain. We've been . . . We ourselves have wondered how exactly do we explain what it is that the Sacra Doctrina Project is. In some ways, I would say it's kind of a mix between an academic society and something like an academic institution. So, what I mean by that is that usually academic societies are where a lot of different people who are academics in a certain field or with a certain background come together and, you know, maybe they have a conference or there's some sort of networking between them. But usually that's about the extent of it. Something you put on your CV. It's good for networking. It gives you sort of a foundation of scholars that you can communicate with ad hoc. And then, so, that's part of it, because it's so . . . SDP is so communal. But unlike most academic societies, we're also trying to do things in the way that an institute might do things.

SHADLE: Okay.

O’NEILL: So, we have all . . . a number of initiatives is what we call them. So, basically, projects that we work on. I'll just name a few. We have an annual conference. We have two podcasts. We run Thomsitica.net, which is kind of an academic site for Thomistic scholarship. We . . . for a while we had a certificate program online that we're maybe going to be launching again in the future.

SHADLE: Okay.

O’NEILL: I’m trying to think. We just also launched an academic journal, peer-reviewed academic journal.

SHADLE: Oh, sure, sure. What's the name of that?

O'NEILL: Lux Veritatis.

SHADLE: Okay.

O’NEILL: Yep. So, it's kind of a . . . it's meant to be a way of bringing together scholars, particularly in theology, but we have scholars from other areas, as well. Philosophy, sociology, history, canon law.

SHADLE: Oh, interesting. I didn't realize that.

O'NEILL: Yeah. So, it's meant to be really a place to effect speculative community among Catholic academics and then, in and through that community, to work on these projects together that are meant to serve the church and the world.

SHADLE: Okay. Could you say a little bit more about what's on the Thomistica web site, just so readers can know?

O'NEILL: Yeah. So, Thomistica has . . . it's been around for a long time. It was founded by Mark Johnson of Marquette University, and then the Sacra Doctrina Project ended up taking it over . . .

SHADLE: Oh.

O’NEILL: . . . and sort of trying to keep up the legacy that he created with that site. Really, it's kind of a . . . It's meant to be one stop shopping for Thomistic news, so any conferences, calls for papers, that kind of thing, that have to do with Thomism. The release of new translations or new commentatorial material is all sort of shared there as a news site for us . . . Thomistic scholarship. But also, we have long form essays, sui generis essays that are written by various academics. We do book reviews, and then there's just a bunch of interesting sort of random stuff about St. Thomas shared on the web site, photographs of people, you know, who've taken pilgrimages to where St. Thomas is, and things like that.

SHADLE: Photographs of Thomas Aquinas.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, exactly. Yeah, not quite that.

SHADLE: Well, maybe that's a job for AI.

O'NEILL: Exactly. Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: So . . . So, you kind of already anticipated, I think, some of the differences, but one question I had is, do you and the other founders and members kind of envision the Sacra Doctrina Project as in some way an alternative to the larger professional theological societies like the Catholic Theological Society of America or the College Theology Society? And you kind of went into some ways there's some . . . it's similar and different than an academic society in general.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But what else could you say about that?

O'NEILL: Yeah. So, I mean, we definitely did not start it to try and compete with any of those societies. I do think that what we do is something a little bit different. I'm sure there's some ways in which maybe we are competing with each other. But not intentionally. I mean . . . the idea of like intentionally competing with another academic society, especially one that's trying to serve the church, I think it would be contrary to the mission of the Sacra Doctrina Project. So, we're not trying to be reactionary or, you know, pit ourselves against some other group. Really, I think the SDP was founded out of a desire to bring together Catholic academics who are primarily interested in how doing theology should be done in, as we say in our mission, it should be done primarily in a speculative and a sapiential mode.

SHADLE: Oh.

O'NEILL: And I mean that we, you know, we could talk about that a little bit, but one of the things that means is that, I guess if we are trying to reclaim something that we think is maybe not as emphasized in other places, those would be the holistic sense of theology. You know, this is something that the mentor to me and multiple members of the Sacra Doctrina Project, Father Matthew Lamb, who passed away several years ago, he would always talk about how theology had become too fractured into sub-disciplines. Now, to a certain degree, of course, you need to differentiate historical theology from systematic theology, moral theology, scripture scholarship, and stuff like that. But all of those sub-disciplines and sub-sciences are meant to come together to form a holistic attempt to understand the faith and to pursue God. And so that idea of not . . . Trying to go in the opposite direction from creating silos within these sub-disciplines and having these sub-disciplines speak to each other so they can come up with a holistic picture. That's a big thing that we’re trying to promote, that I think is not as valued, maybe, in other places or as valued in the larger academy as it could be.

SHADLE: Well, and that also reminds me. . . and maybe not to get too much into controversial waters, but Paul Griffiths has raised a similar criticism,3 but more there's so much methodological diversity in theology that it’s almost as if we're talking past each other. It's hard to say we're all doing the same thing. And I've written with some, you know, criticisms of that.

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But I think it’s a good question to raise. And so how would you all, you know, respond to that kind of issue?

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, well, that's where I think intentionally trying to form a community of scholars who don’t just, you know . . . membership is not really just something you put on your CV. But one of the things that’s sort of the heart and the soul of SDP is that we have a multi-layered like 25 channel ongoing chat that’s pretty lively amongst the members. And so what that means is that even though we're, you know, at different places all across the country, and across the world, there are always, every day, ongoing conversations about all manner of things, some of them having to do with professional development and what does it mean to be a professor or a scholar, to teach effectively, and things like that. A lot of them are about speculative questions in theology. What does St. Thomas really mean by this or what does St. Augustine really mean by that? That kind of a thing. And I think what that does is it forms a community, and it allows us to learn from each other on an ongoing basis. And it really forms friendships. And I think friendships and doing theology communally, socially, is so important. And that's maybe something that gets pushed aside a little bit when theology, and academia in general, really becomes both siloed into sub-disciplines, but also about a kind of individual pursuit of credentials and padding out your CV and that kind of a thing. Not that it’s bad to publish. I mean, those things are really important, and SDP has been trying to effect that. You know what I mean. The idea of community within theology and philosophy and other disciplines, I think, is essential, and that's what SDP all about.

SHADLE: On the other hand, in the past couple of decades, there have been some other organizations or groups that maybe have some overlap in terms of their vision of theology, and what came to my mind was the Academy of Catholic Theology. There’s probably even some overlap in people involved in Sacra Doctrina and the Academy of Catholic Theology.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yep.

SHADLE: Although, I mean, I’ve got to say, like, reading their mission, it seemed like the intent was, they really emphasize these are theologians faithful to the Magisterium, and you know, however they interpret that.

O’NEILL: Yep, yep.

SHADLE: Which is obviously meant to imply that, you know, at the CTSA that's not really a focus, but . . .

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: And not to say, obviously, the people involved in Sacra Doctrina Project wouldn’t have the same concern, but that's not really what you all emphasized in your mission. It was more like you said, the speculative and sapiential dimension of theology. But anyway, my question is, how do you see the relationship between Sacra Doctrina and other groups like the Academy of Catholic Theology?

O'NEILL: Yeah, I think ACT is probably the closest to us just in regard to membership. So, we do have members that are part of CTSA and other things, but I think that probably has the greatest amount of overlap. I do think, though, that, even with ACT, I think that there's a real way in which ACT . . . I don't want to speak on behalf of ACT, I’m a member of ACT, but I don’t want to speak on behalf of ACT. But I do think that ACT, for as long as it's been around, has really been primarily about getting scholars together who have a kind of similar view of what it means to be faithful to the Magisterium, and then they get together once a year in Washington, DC, and it's great. There's papers given, its good networking and to spend time with people. But SDP is a little bit more sort of outward facing, I guess is what I would say.

SHADL: Oh, okay.

O’NEILL: Attempting to not just to be communal with each other, but to take that community and to use it as a impetus and a cause for working together in the service of the church through these various initiatives that we have and doing that communally. So, there's a little bit more, I think, of an emphasis on doing something together, if that makes sense, and not just networking and speaking together.

SHADLE: Yeah, sharing your research, right.

O'NEILL: That's right. Sharing research.

SHADLE: And like you said, as important as that is, that's not everything, right.

O’NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, right, right, right.

SHADLE: So, shifting gears a little bit, though, but you mentioned this a couple times, but one of the foundational principles of, I'm just going to say SDP for now, is that theology should be sapiential.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: One thing I noted to you as we've been communicating is, Pope Francis said the same thing! Right?

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: So, in his document Ad Theologiam Promovendam,4 where he was kind of outlining the guidelines for, oh, I forgot the name, but it's not the International Theological Commission, but the Academy of Theology or something like that.5

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: And so the way he described that was . . . This is actually kind of funny. He used the phrase, like, “theology on its knees” or “a kneeling theology,” although he didn't cite Balthasar, though Balthasar’s most well-known for talking about that.6

O'NEILL: Yeah. Right, right. Yeah.

SHADLE: But basically, that theology needs to be rooted in prayer. But he also talks about it, it needs to be like the purpose of theology is to draw us towards love of God rather than being this purely intellectual exercise.

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: So, how do you all understand the sapiential dimension? Is it very similar to Pope Francis or you emphasize kind of different aspects?

O'NEILL: No, I think it's very similar, I think, yeah. There's different aspects to what it means to call theology sapiential. I think that the first and most important is exactly what you were just citing Pope Francis as having said, which is theology is meant to be done in concert with prayer and contemplation. And one of my favorite quotes, it’s a similar, very similar sentiment from someone in many ways theologically very different from Balthasar, but I think also very consonant in other ways. Garrigou-Lagrange says that theology needs to see itself as John the Baptist, right.7

SHADLE: Okay.

O’NEILL: And he says theology needs to see itself as John the Baptist, and that means that it should always be pointing toward Christ, and it should be forgetting itself as it points toward Christ. And I think that's really key, so that theology is not being done for its own sake. Theology is not being done . . . I mean, obviously in the academy it's easy in any discipline to fall into wanting to pursue the thing that you're interested in or writing about in order to make a big name for yourself, sell books, etc. But even beyond that, theology and theological knowledge is, although it is a good in itself, it's a good that's meant to be ordered beyond itself, and it's meant to be ordered toward the love of God and the knowledge of God so that we can commune with God. So, theology should and must always be ordered beyond itself to prayer and contemplation of God. And so that's one thing I would say. And then the other thing I would say is that I think sapiential theology is, and this goes along with the breaking down the silos between disciplines and sub-disciplines . . .

SHADLE: Okay.

O’NEILL: Theology really should, at the end of the day, be about attempting to understand what's true about God and what's true about revelation. So, there's all sorts of place for textual criticism and historical theology, and those are really, really important. But they are not the sort of . . . the purpose of theology, the end goal of theology. The end goal of theology is to understand better what revelation teaches us about God. And that's ultimately what's most important, and the questions about what's true are the most important questions that theology asks.

SHADLE: I was hoping you would bring that up because I think that was something that stood out to me about the SDP’s mission, too, was the insistence that we can in fact approach the truth, you know, like that, you know, we . . . maybe only at the eschaton will we, you know, fully realize . . . I'm riffing here, and this is not like in the mission statement or anything.

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But that truth is something that we can come to know. And . . . Obviously I know other theologians would object, but this criticism that there's, I think maybe from some of the pressures of higher ed, of the academic world, to . . . the way it was phrased on you all's mission statement is in the pursuit of novelty, you know.

O’NEILL: Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: Just coming up with new perspectives on things as almost like an end in itself, you know.

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: And new theories or new perspectives, when in reality the goal should be understanding God.

O'NEILL: Yeah, exactly. And I think that’s . . . The academy is in many ways sort of self-inclined towards wanting everyone to come up with sort of new ground-breaking ideas, and so I do think that, boy, of all the sciences, in some way, the science that’s probably most . . . has the most potential, if you want to put it that way, for ongoing development of thought is the sacred science of theology, because the object is infinitely beyond human comprehension, so there's always something . . . There's always something more to be said about God, right? It's theology of all things that can never get stale. I don't know. I'm sure physics and things like that, they also . . . there's always something more to learn, but I mean, at some point that might not actually be true. You might be able to have a comprehensive knowledge, at least some mind could have a comprehensive knowledge. But in theology, it's not like that. So, on the one hand, I do want to, yeah, sort of say that there's always something more to be gleaned, but new ideas for the sake of new ideas is silly.

SHADLE: Right.

O’NEILL: I mean, that's kind of an absurdity, especially in theology, where what we're trying to do is, we are trying to understand God better. And so especially when what you're talking about is a sacred object of study, you don't want to just be willy nilly coming up with ideas because they're interesting and people haven't heard them before. That's not what theology is all about.

SHADLE: As we're talking, I'm thinking it's like, in a sense, we need the sense that we're, you know, just gradually building on the work of others and contributing to future generations. But there's something about academia that works against that, and it's not at all limited to theology or even the humanities. Because even . . . Like, I was thinking, even in the natural sciences this is the problem they really have that hardly anybody does research to replicate someone else's research.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: Right. That, you know, you only get tenure or you only get promoted if you do groundbreaking research.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yep.

SHADLE: Nobody gets tenure for trying to replicate that groundbreaking research.

O’NEILL: Yeah, yeah. Yep.

SHADLE: But then we have kind of a, you might call it an epistemological crisis. Like, well, nobody even knows if these studies are valid because nobody is replicating them, right.

O’NEILL: Yeah, exactly. I think that's right. And I think in all disciplines, but also and especially in theology, there's something to be said for . . . Have you ever read the novel Canticle for Leibowitz?8

SHADLE: No.

O'NEILL: Okay, so, I mean this is not really giving anything away, but the basic setting is there's a monastery. The world is essentially in a post-apocalyptic state of things. And one of the things that the novel does a really good job of, I think, is just showing you the beauty, the absolute importance of just keeping the torch lit and passing it on to the next generation. Just keeping the torch lit of the Church's teaching, of knowledge, etc. And so, I do think that the importance of just handing on what we have received, as scholars, as Catholics, whatever, is really undervalued. I think that's really important, and we should collectively, I think, be gaining new insights all of the time in revelation. But it's not as if, if you haven't contributed some amazing new insight that gets you an endowed chair at an Ivy League school, that that means that you've wasted your life as an educator in theology.

SHADLE: Yeah.

O’NEILL: Because just understanding, right, understanding what has been, you know, we’re always working on the shoulders of giants. Understanding what the tradition, all of this, this hard fought knowledge and wisdom that has taken centuries and centuries of bright minds, prayerful minds, contemplating scripture and revelation, all of that stuff, to be able to take some of that in and understand it and hold it at least long enough to pass it on to the next generation so that it keeps going: That's immensely important, and I think we don't recognize that enough in the academy. We think unless you do something really novel, it's like, what's it been for? Well, just to keep the light going, to keep the fire burning, is incredibly important.

SHADLE: I want to circle back to this issue, but I want to get something else in the mix first, and then we'll come back to this issue of the theological vocation or the theological discipline. So, well, let's . . . Okay, yeah. Two questions then, actually. So, my next question is, is the Sacra Doctrina Project a Thomist project? And you might remember when I first sent this question to you, I even put the little devil emoji, and I did that because maybe your answer might get you in trouble with some of the other members, maybe some of you think it is, some of you think it's not, so is it a Thomist project?

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, no, I'm glad you asked this. And it is something that we've talked about a lot, and I think there's actually . . . Yeah, this will not get me in trouble thankfully, and I know that because we've collectively as a group, we've talked about this a lot. It’s not. It is not an explicitly Thomistic project. Now we do have many Thomists, but we have members who are not Thomists, at least not in the traditional sense. It's not the case that they primarily study St. Thomas, or that they think Saint Thomas is the be all end all or anything like that. So, SDP is intentionally, I would say, big tent in regard to theological schools. So, we have Balthasarians, we have those who are . . . We have several members who are, I don't know exactly what their titles are, whatever, but they have some sort of official affiliation with the English edition of Communio.

SHADLE: Yeah.

O’NEILL: We have people who are interested in non-Thomistic medieval theologians. We have people who are primarily . . . they study the Church Fathers and they maybe disagree with St Thomas on a number of his interpretations of the Church Fathers.

SHADLE: People who kind of draw on the longer Catholic tradition of moral theology, which has, you know, some strong Thomistic roots, but has incorporated other elements over the centuries, and including, like Pope John Paul II’s teachings, which, you know, in some ways Thomistic, in some ways not.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Exactly. So yeah, we're intentionally big tent. And the idea is that, not that individual members can't think one theological school is more correct or a better starting point than another. I mean, I think most people have opinions about that. I know I do. But all of these different schools in so far as they are attempting to understand God in and through a faithful interpretation of revelation, they are all pursuing the same thing, and there are . . . The most holistic and sort of pregnant way of understanding the whole of the tradition, I think, is to do it in and through all of these traditions speaking to each other, not just necessarily singing “Kumbaya” and saying, “Oh well, you know, our differences mean nothing. And, you know, there's no truth,” or anything like that. But in and through really passionately discussing the differences and the areas of congruence between these schools and doing it together in a fraternity of friendship. That's key, I think, and that's what's most important for aiding the church and for helping all of us understand God better and what the church has handed to us better.

SHADLE: So, building on this, the big tent you mentioned. So, one of the upcoming initiatives is next year's conference on the theme of scholasticism and ressourcement. So, let me just give a couple of seconds to explain to listeners what ressourcement is. It’s a big French word. So this . . . I've actually written about it in the Window Light newsletter, but it was a movement in early 20th-century theology that was . . . Well, I mean, some of the roots were simply trying to provide critical editions of the Church Fathers to make them more readily accessible to scholars and other readers. But also the discovery of theological insights from the Fathers that in some ways cut against the Thomistic orthodoxy of the time, and so most famously, there was a theological dispute over the natural desire for the supernatural. So, the Jesuit Henri de Lubac was the major figure there.9 But also, and this is more what I wrote about in the newsletter, also just some disputes over the extent to which we ought to historically contextualize theology, right. So, like, the Dominican Marie-Dominique Chenu, a major figure on the side of ressourcement.10 And then it ends up having a major influence on the Second Vatican Council. So, many of the theological experts at the council come from that, and there's some other modern theologians who aren't really identified with ressourcement like Karl Rahner that are influential, as well, okay.11 But, you know, point being, the ressourcement theologians and the Thomists were opponents, and with, you know, real life consequences for people. Some like de Lubac and Chenu had . . . were disciplined within their orders, you know, or for periods of time not allowed to publish their writings. But okay. So, you all have advertised this as an opportunity for dialogue. And well, earlier you mentioned some of the members are affiliated with the English-language journal Communio, which is one of the inheritors of that ressourcement tradition. So, an attempt to bring these two traditions into dialogue. So, tell us more, like, what do you all see as the purpose of this conference?

O'NEILL: Yeah. So, this has been something that has been an ongoing, long, long going on conversation amongst members of the Sacra Doctrina Project, I think. And I think the reason for that is that probably the two largest groups of members, in terms of just the school, if you want to put it that way, that they come from, that they were trained in, are Thomists and those trained in broadly ressourcement theology, especially Balthasar, de Lubac, Daniélou, and a few others.12 Bouyer.13 And that conversation has been, for years . . . for all of us involved in that conversation, it has been immensely fruitful. And so, I think what a lot of us realized . . . And yeah, I mean, in a way, I hate to say this, but I think what a lot of us realized is that, that whole moment in theology was so . . . It was like a powder keg, right? There was so much tension. There was so much personal animosity on both sides of the debate, that it was almost like both sides retreated into their camps and no longer engaged with each other or with each other's ideas. It was so tense at the beginning, it was so hot, such a . . . like a live, hot war, that in order just to keep the peace, like both sides sort of retreated back. And so, I think a large number of us really think that, as the dust settles from those initial debates and as the characters, the personalities, historically, who were most associated with that powder keg have passed on and their first generation of students have now passed on or are in the process of passing on, there's been a little bit more just sort of calm amongst theologians within the church, and it's now, I think, that the time is ripe for both sides to be able to speak to each other, have speculative conversations about places of agreement, places of disagreement, but do it together in a spirit of charity and friendship, and not have it just dissolve into animosities, if that makes sense. And so, I think the time is ripe for that. It's really, I mean, one of the things I guess I would argue is that we're just now getting to the point where that whole disagreement could probably start to really bear amazing fruit for the church as a dialogue, as a conversation between these two schools or camps or whatever you want to call them.

SHADLE: And in addition to what you've said, it's also, you know, there's been evolution in the two camps. And so, just to give one example, people now talk about ressourcement Thomism, right.

O’NEILL: Mm hmm. Mmm hmm.

SHADLE: So, it's now been several years, but a book came out with that title.14 I actually reviewed it, but I think that, wasn’t that Matthew Levering and maybe Thomas Joseph White?

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, I think that's right. Maybe was it Michael Dauphinais involved?15 I can't remember. But yeah, I think you’re right.

SHADLE: But the idea here, you know, taking that historical approach of, you know, situating Aquinas’s work, but also just Thomism, like the Thomist tradition, situating them in their historical context, but using some of the tools that the ressourcement theologians had introduced.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: So not as much a rapprochement in the theologies but more like the historical aspect of that, it's kind of what they meant by ressourcement Thomism.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But also, I mean, I got to say, my impression is also . . . And you can counter me if you don't agree, but part of this coming together is . . . I wrote about this . . . but that, at least for the Communio theologians, they felt like the previous two popes were like, I don't want to say "Were their guys,” as if there was a sense of ownership.

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But in a sense that, you know, this sense of connection with them. But now there's this sense that Pope Francis, “He's not one of us,” you know, and maybe uncertainty about what exactly he is, you know.

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: I know some people said, “Oh, he's a Rahnerian.” I don't really think that's the case.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: And so maybe Thomists and Communio theologians have seen some similarities that they didn't really recognize before.

O'NEILL: Yeah, I think that's absolutely true.

SHADLE: In this new situation.

O'NEILL: Yep, I think that's absolutely true. And I think that there's something to be said, too, about . . . Even in just my personal experience studying in graduate school, studying alongside people who are dyed in the wool Thomists . . . And I would identify as a dyed in the wool Thomist. I think I'm . . . I'd like to say I'm an inclusive Thomist, so I think that Thomists can learn a lot of things from people who aren't Thomists, and I know there's sort of this caricature of Thomists as, you know, incredibly stuffy, closed-minded, sort of, whatever. And I don't like that sort of picture of Thomism, to whatever degree it's real. But I think there's something to be said about studying alongside people who are really interested in Benedict, people who are really interested in de Lubac, people who are really interested in Balthasar, and then people who are really interested in Saint Thomas, who are really interested in Bonaventure, or whatever, but all of us together sort of sharing the same love and zeal for the church and for the science of theology. That, in in a lot of ways, just that experience, that forming of friendships across the aisle, if you will, I mean, that's really big, that shows people, “Oh, we do have all these similarities, and there's a lot that we can learn from each other.”

SHADLE: Well, and I doubt you would want to frame it as some kind of anti-Francis alliance. I don't really think that’s the idea.

O'NEILL: Yes, I definitely . . .

SHADLE: Although sometimes it does kind of come across that way. But actually, as I was speaking earlier and listening to you, it's . . . I mean, I guess it's also, it's really something that was emerging long before Pope Francis, but in the fact that within the theological guild, I mean, obviously Thomists and Communio theologians are not the dominant school of thought.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: And so being in the common position of minority voices, like I said, maybe a realization, “Maybe we have some things in common we didn't realize before,” given this situation in the theological field.

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, I think that that's probably another huge aspect to this. Just what you were saying that, in a way, both the Thomists and the, broadly speaking, the ressourcement folks are now both in the minority and that there's been a way of bringing them together. But yeah, I certainly don't think the beginnings of this . . . I wouldn't even call it a coalition, I would just call it a real willingness for both of these sides, an interest and a willingness on both of these sides to reanimate the discussion in a positive way. That willingness, I think, has been bubbling up for some time. I don't think it has anything to do with Pope Francis. I don't think it's reactionary to anything going on in the church, not principally. I really do think, and if you disagree I'd love to hear it, but I really do think that a major part of it is just that this was a major moment in the church, and in a way, it's a kind of . . . It was as if we hit a moment in the church where the note sort of ended on dissonance and hasn't been resolved. And so, there's all of these myriad questions about what is the antecedent Thomistic tradition’s place in the church? What is the place of the ressourcement movement, and how do these two traditions, which are clearly important, how do they come together? How do they come together to form a holistic, singular contribution to the church and . . . and I think we're still waiting to reach the resolving note of that dissonance. But I do think that that moment is going to come, and I think that, again, because of the historical particularities, it's almost like now the stage is set, the fires have cooled down. The stage is set for people to take up that question again and to start working through it together.

SHADLE: So, earlier I said I wanted to circle back to the question of theological method. And we kind of already have talked about these different schools, but . . . So, one of the other characteristics that Pope Francis had identified as crucial, excuse me, crucial for theology today is that it should be contextual, and that's where Francis got some pushback. The one I had . . . Well, actually, I responded to several people, but one was Larry Chapp, who is, you know, associates himself with the Communio school.

O’NEILL: Mm hmm.

SHADLE: Now I forget the name off the top of my head, but another was a Thomist. But related to something, it was something we were talking about before, that I think, you know, many theologians today would say it's not so much that we're pursuing novelty for its own sake, but there's a recognition that the tradition is enriched when we have theology done from different contexts, whether it's, you know, Hispanic theology, or black theology, or feminist theology. But also historical context. So, a theology of, well, you know, a theology from the Global South, or a theology responding to the, you know, the technocratic realities of today. That yes, you know, that can kind of get sucked into those negative aspects we were talking about, but really here there's a motive of . . . really the tradition is theologians and others working from different contexts, continuously enriching the tradition in different ways. So, like, what do you think of that?

O'NEILL: Yeah, well, that's a great question and that's a huge question. I guess I'll just . . . I can offer a few thoughts.

SHADLE: One of those that's more of a comment than a question.

O'NEILL: Yeah. No, no. I think it's . . . I mean, you're touching on, in many ways, the state of contemporary academic theology, and it's so important. Yeah. So, I mean, I think you're absolutely right that the universality of the church means that there are many different contexts in which theological study and contemplation can bear, not novel, but bear unique fruit and provide unique insight that other beginning points and other contexts cannot. And that's essential. I think that's really . . . And the church has borne that out for the last 2,000 years. So that, I think, is wonderful. I am . . . Sometimes I do think that it can go so far as to preclude, however, the universal, that the, sort of, the return to the universal is the ending point, so that, I think, as long as theology is ending, no matter where it's beginning, as long as it's ending in an attempt to faithfully unpack what has been revealed to us by God and to present that in a way that is universally, that is sort of universally true, then that theology is doing, at least in some way, what it's supposed to be doing. But it's got to be in some way universal, and it has to be . . . I think it has to begin from, it can begin from a particular perspective regarding what's been universally revealed, but it has to begin and end with that universal of revelation, because revelation in toto has been given to all human beings, right, and has been given to the church as a whole. Does that make sense?

SHADLE: Yeah. And I mean, this might take us too far afield, but I think then that . . . that really gets to the heart of some of these differences. I think many would argue, then, revelation itself is something that we experience, and then that experience is always in some sense shaped by our context.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: So, but I don't think you and I disagree on that.

O'NEILL: No, I think that's true. I think that's true. But it's so tricky, because you also, you want to be able . . . I mean, theology as a science needs to be able to gain insights from, if you will, the subjective way in which I receive revelation, but it also needs to break through that, and it needs to end in some way, it needs to end with contemplation of what's sort of universally true, what's true of God qua God.

SHADLE: Uh huh.

O’NEILL: And that should be something that's able to be shared, right, across all of these different starting points. But if we don't break through from the particularity of the starting point, then, in a way, I worry that we're remaining siloed, that we're remaining siloed or what we're breaking through toward is not actually the universal object of God and the divine essence and how that's revealed in in divine revelation. So, just for example, I have nothing against activism. But I do worry, and this is not just about theology, but there is the tendency in academics today, I do think, to orient study toward the practical. And the practical is immensely important, don't get me wrong. You can't just get rid of the practical, but ultimately the science of theology, which I do think is a science, it's ordered most properly towards the speculative, so it's ordered most properly towards knowledge of things. Knowledge of God. Not so that I can perform X or Y practical action or change the world in X or Y practical way. I have to do that, too. Again, don't get me wrong, this is not . . . You can't just sit in your chair while the poor are starving and whatever. But ultimately, what theology is, it's a speculative science. And so, what theology is ordered toward is a knowledge, a knowledge of God that's good for its own sake. It’s not good just for this or that reason, because I can do this or that with it, but theology should remain in that mode, or it should at least always end in that mode, if that makes sense.

SHADLE: Yeah, and spoken like a true Thomist.

O'NEILL: Exactly. Yep, yep.

SHADLE: Okay, so let’s . . . I have completely lost track of how long we've been talking, but I know it's getting late. So, let's talk a little bit about your book, Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin. So, first of all, before we really get into the contents . . . So, obviously the topic of the book is the doctrine of predestination in the Thomist tradition, and that was actually something that was interesting to me, that you exclusively focus on the discussion within the Thomist tradition. So, you only briefly mention the Molinists and don't really mention any kind of contemporary perspectives or anything, or Calvinism or anything.16 So, my question is, before we get into the content, so what, first of all, interested you in the topic of predestination? But then what . . . Why do you think your work on predestination might be of interest to others, as well?

O'NEILL: Yeah. What initially got me into this was, I think when I was still a master’s student, Prima Pars question 22 was brought to my attention, and my initial reaction17 . . . this is the question on Providence . . . and my initial reaction to it was that St. Thomas is clearly wrong because St. Thomas says that everything is ordered infallibly by divine Providence, and so my immediate thought was, as most people's immediate thought is, that, “Well, this does away with everything, this does away with contingency, this does away with free will, whatever, and so how could, how is it possible that St. Thomas Aquinas could hold something so obviously stupid, right?” That was my basic, initial response. And so, I started reading some of the commentators about this, and I tried to start writing my master's thesis at CUA against the Thomists on this question.

SHADLE: That’s so funny.

O’NEILL: As I was going . . . Yeah, yeah. Isn’t that funny. As I was going through this exercise, I was slowly converted by the Thomistic commentators and completely came around to their position. That's what initially got me into this. And then when I was doing my doctoral studies, I realized that, there had been relatively a lot of things that have been written about the sort of famous De Auxiliis debate between the Dominican Thomists and Molina and his followers in the Jesuit order. And there's been a lot . . . I mean, relatively a lot, written about Thomas and Jansen and Calvinism, and things like that. But there had been very little written about an intra-Thomistic debate that took place in the 20th century. And that was sort of the old school, Bañezian traditional Thomistic interpretation of St. Thomas’s doctrine of predestination and Providence,18 and then what I called a kind of reforming movement within Thomism in the 20th century, most famously Jacques Maritain, but several others, a Dominican Francisco Marín-Sola, Bernard Lonergan, the Canadian Dominican. I put those sort of on the reforming camp.

SHADLE: He's a Jesuit.

O'NEILL: Oh, was he a Jesuit? That's . . . Well, okay, there we go. I get confused because he's such a, in many ways such a, like, great Thomistic commentator.

SHADLE: Well, right, right.

O'NEILL: I just assumed he's Dominican. But anyway, so very little had been written about that debate within the Thomistic tradition. And so, for the most part, that's what the book is about.

SHADLE: And so, my sense is, I mean, that there is this interest in predestination, but maybe broadly Providence, I mean, I mean obviously it's . . . I mean, I would say it's obviously . . . I'm not an expert in this, but it seems to be that's pretty big in evangelical circles.

O'NEILL: Yes. Yeah.

SHADLE: But even in Catholic circles, thinking about, I guess you would say God's role in history and where it's all going, you know, like we'll talk about this later, but for example, this new interest in universalism, for example, I would fit into that.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But also, a lot more people like you interested in the Thomistic perspective on predestination

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: And I think it's interesting because, you know, as we'll talk about, there was, you know, conversation about this early in the 20th century.

O’NEILL: Yep.

SHADLE: Kind of the tail end of that controversy, going back to the 16th century, but it seems like from the middle of the 20th century on, just . . . the focus was just on other things, right.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, there was so little written over a 50 or 60 year period of time. It's really funny how these things happen, they really do come sort of in waves in the church.

SHADLE: Yeah, and I guess . . . I'm sorry, go ahead.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Well, just in the church and in the academy, something gets brought up and it's a really hot topic for a while, and then for whatever reason, it falls by the wayside. And then all of a sudden it seems to crest up again. I think we're seeing, definitely, it's cresting back up again, as you said.

SHADLE: Yeah. And I guess somewhat the exception to that would be, you know, Balthasar’s Dare We Hope.19

O'NEILL: Yep, yep.

SHADLE: But that's more about, that's more just eschatology.

O’NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, I think that's right.

SHADLE: And less about Providence, you know.

O'NEILL: It's. And yeah. Yeah. I . . . Yeah, in some ways, I wish that he had written a more systematic treatment of just what he thought about predestination and Providence. But I think that's the closest you're going to get. But as you say, it's not really about that. But yeah, there's been this influx in interest in this, and I don't know exactly what brought it about, but it's . . . I mean, it's been wonderful, it’s been great fun, to be around and part of it has been really fun.

SHADLE: And actually, so I . . . You may have seen it, maybe not, but I wrote something that touched on, not predestination, but that question of Providence, back earlier in the summer where there was that first assassination attempt against Donald Trump.

O'NEILL: Oh yes, yeah.

SHADLE: You know, some were claiming, you know, God intervened to save his life.

O’NEILL: Mm hmm.

SHADLE: And others, I think you know, made some valid criticisms of that, but I . . . I don't want to call it a middle ground, but I was like, “Well, wait a second.” Like, the more traditional view of this question, “Did God save Donald Trump,” is, “Well, of course he did,” right?

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: Of course God did because . . . But not through some kind of intervention.

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: Because that suggests the world . . . that the normal state of the world is God's not active. Then God intervenes to do something, right.

O'NEILL: Exactly, yes, yeah.

SHADLE: And I really appreciated that something you emphasized in the book is that one of the starting points of these Thomistic reflections on all of this is that we have to understand that God is active in everything, right, that created things can't act without God acting.

O'NEILL: Yeah, exactly. Yeah, that in a way that this, the notion of divine intervention is itself sort of nonsensical.

SHADLE: It’s very modern.

O'NEILL: It is very modern. Very deist. I mean this, this presupposition that we have that the world, for the most part, is sort of running autonomously from God, and then every now and again he's like a great machinist, you know, every now and again he's kind of, “Oh, no, I didn't expect that to happen!” He's got to come in and pull a few levers and hit a button or, you know, put some grease on one of the levers or something, like, just to make sure that it starts running normally.

SHADLE: Uh huh. Yeah.

O'NEILL: Again, I mean, that's just . . . it's insane, right? I mean it's a kind of, I mean, I would argue it's sort of a form of, at least speculatively, it's a form of idolatry, right? To think of God this way as just this great actor within the same arena as us, who's just trying to keep everything running.

SHADLE: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And that gets into, really, I think the key issue in the book. There are disagreements amongst the Thomists on what exactly that means, right. And the fear among some of these 20th-century Thomists that you highlight is that the, I'll just say Bañezian, but you argue is the classic Thomist tradition, they fear that it verges on kind of like predetermination, I guess you would call it determinism, and also that it implicates God in evil.

O'NEILL: Yep, yep. Yeah.

SHADLE: And you know the book, I got to say, the book is highly technical, although I found it readable, as well.

O'NEILL: Good. Thank you. Yeah.

SHADLE: But so, without, you know, like I said, without rehashing the book.

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: You know, how would you describe this dispute? And maybe you could leave Lonergan to the side, because . . .

O’NEILL: Yeah, he’s sort of doing his own thing.

SHADLE: I think the issues there are different than the others and very, kind of very technical.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, no. I think really what it comes down to is how you understand grace and what it means to say that grace is always and of itself efficacious. So, I mean really, in a way, kind of all of this comes home around Jacques Maritain's statement that grace can be shatterable, as he puts it, so that God can give you a grace, and that you can shatter that grace. You can refuse that grace, and that said refusal is not itself something that God antecedently permits, or that the not shattering of a grace and cooperating with God is not something that itself comes from God. That's kind of Maritain's position in a nutshell. I mean, it's oversimplifying it. And the reason why . . . Go ahead . . .

SHADLE: Another word that’s sometimes used is that grace is frustrable. Am I pronouncing that right?

O'NEILL: Yeah, that's right . . . I think that’s right.

SHADLE: That’s kind of a weird word in English.

O’NEILL: It is, yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: But, like, that God, that God's will can be frustrated.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yeah, a lot of these are words that were coming over from French, and then people are just trying to translate them into English and there’s no good word.

SHADLE: Yeah, that’s right.

O'NEILL: Yeah, I think that's really what it comes down to. So yeah, the more traditional position . . . So yeah, what I would argue is that the Bañezian position, the more . . . what I would argue is the more traditional position, both sides agree that grace is not irresistible. And this is what I would argue is fundamentally at least one of the things that makes the Thomistic position really distinct from, say, Calvin and Jansen.

SHADLE: Uh huh.

O'NEILL: So, grace is not irresistible. The question is, is it possible for . . . Essentially, is grace, although it's resistible, is it infallible or not? Does the effect that God intends to come about through the grace, does that effect definitely come about or is it possible that the effect doesn't come about even though God is attempting to bring that effect about? And that's really what I think this intra-Thomistic debate was all about. The Bañezian position is to say what God wills simply and actually will definitely take place, so that the idea that God can be, if you will, attempting to definitely make Bob go and take out the trash, for example, and yet Bob is able to frustrate the divine will and shatter that grace, such that the grace becomes inefficacious, that Bob is able to do that, and able to do that in such a way that God is in no way permitting that, but God is like, actually like, “No, no, no, please, please do it,” and Bob is still somehow able to not take out the trash, that that position is ultimately untenable. That’s kind of the Bañezian retort to Maritain's position.

SHADLE: Yeah. So, I think we should start wrapping things up.

O'NEILL: Yeah, sure. Yep.

SHADLE: But earlier I mentioned that there's been a renewed interest in universalism, and interestingly, some terminology, some kind of informal terminology, has been developed, so that some people call it “hard universalism,” like that all will be saved, not the “soft universalism” of Balthasar, like Bishop Robert Barron, that we can hope that all will be saved, but ultimately we don't know. So, the person most associated with this is, of course, David Bentley Hart. And actually right before we logged in, I saw that you had actually reviewed That All Should Be Saved,20 or that it's forthcoming anyway, so maybe you may have more to say on this than I anticipated.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But my question, in true scholastic fashion, I want to ask why . . . Well, what do you think is the strongest point in favor of universalism? But then why do you find the Thomistic perspective on predestination more convincing?

O'NEILL: Yeah. So yeah, this is the kind of thing that gets me in trouble with all sides. I am sort of a Bañezian-Augustinian-Thomist, but I am immensely sympathetic to the so-called hard universalist position. And one of the things that I think is really fascinating is that the hard universalists like David Bentley Hart and the Bañezian Thomists like myself, although in some ways we are the most . . . the furthest apart from each other on the question of hell and things like that . . .

SHADLE: Yeah, I think I know where this is going . . .

ONEILL: We actually share all sorts of views about grace and human freedom and things like that . . . I mean, David Bentley Hart says things that only a Bañezian Thomist would say, and the only other type of, you know, theologian who would say them would be a Bañezian Thomist. And so, there's a lot of really interesting overlap there. I think most other theological traditions or starting points think that the question of whether God could save every soul is a really difficult question and whatever. But for David Bentley Hart, as for myself, for other Bañezian Thomists, it's a really easy answer. The answer is yes, absolutely. It's the easiest thing in the world for God to save every soul. So that's . . . But that already puts you at odds with a lot of people, right? So, I find that as a starting point, and the view of the compatibility between divine causality and human freedom that that idea flows from is right on the money. I mean, I agree with it 100%. And so, then, it really just comes down to the question of, well, whether is it indeed true that God does save all. Because it's clear that he can. And in many ways, I think the hard universalist position is the one you would expect to be true. I mean, once you essentially do away with the free will defense and this idea that, well, God is trying to save as many souls as possible, but he just can't quite muster it, you know. That view, once you do away with that view, which is, I mean, I think it's, in a way, it's by far and away the most prevalent view in in the church. But once you do away with that view, there is a real way in which it seems absurd to think that, well, if God could save everyone, of course he would, then. And so, I find all of that incredibly intelligible from the side of David Bentley Hart. And the reason then, that I disagree with him is really simple. And I . . . and I'm sure it's very . . . feels like punting or anti-climactic for a lot of people, but I just can't wrap my head around Scripture and the tradition in light of the claim that all souls are saved. In other words, it just seems to me true that it is part of the ordinary Magisterium of the church, and pretty clear from Scripture, that indeed not all souls are saved. And, in a way, that puts me in a really difficult position because I see all of the logic of the other position, and yet have to attempt to answer the question. What I think is at least the most difficult question that I've ever been faced with from my students or whatever is if God can save everyone, why in the world doesn't he? And that's an arresting question, and I think that anyone who believes in hell, and especially who holds the view that I do about God and human freedom not being competitive, if they're not arrested by that question, then something's gravely wrong. So, I'm arrested by that question. I will probably spend, God willing, whatever time I have to think and write about these things on that question, because I find it endlessly interesting, and also sort of impossible to answer. I don't think that it's the case that there isn't an answer. I just think that the answer to that question is deeply mysterious. And so I . . . Ultimately maybe that's my biggest difference with someone like David Bentley Hart, that I think his answer to the question of evil, and especially the question of damnation, is just, it's sort of too neat. It packs everything up and puts a bow on it, and the question of evil is sort of entirely solved. The wayfarer is able to answer it completely, and I guess I'm, in a certain way, comfortable with resting in not resting, you know, not having a solution to that question, because I think we're meant not to have a full answer to that question. And we should worry if we think we have a full answer, if that makes sense.

SHADLE: Yeah, yeah. And actually, so, just kind of to recap. But yeah, I kind of . . . I thought that would be your answer to that first part is like this . . . I don't know if David Bentley Hart uses the language of sovereignty.

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But like the idea of God's sovereignty. That God infallibly fulfills God's will. That that's something that Thomists and Hart and universalists would both emphasize.

O’NEILL: Absolutely.

SHADLE: Like you said, the idea that God wants everyone to be saved but somehow fails to do so is, to use a phrase you used earlier, insane, right?

O'NEILL: Yes, I did say that. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: It doesn't work. And actually, I wonder, you know, I opened this section of our conversation . . . You know, what do you think is driving this renewed interest in both predestination and universalism? Maybe that's it, it’s maybe a sense that, maybe, despite appearances, God is in control, right?

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: I don't mean that in like a psychological coping sort of way . . .

O’NEILL: Mm hmm, mm hmm, mm hmm, yeah.

SHADLE: But, you know, a renewed sense that as Christians we need a sense of God's Providence, that things are in God's hands. So maybe that's part of it. That's kind of an interesting thought. But yeah. So, going back to, then, the disagreement. Just, you know, in your book, one of the things that comes up, it's not of course a major focus, but is that for Thomas . . . I guess if we could somehow put Thomas Aquinas and David Bentley Hart in dialogue, it seems like Aquinas would say we can't say that the salvation of humankind is the one thing that God wills, right?

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: That God's will is . . . I'm not using technical language . . . but complex, right. And that that's what Aquinas himself says, that the reprobation of part of humankind is also something that God willingly permits.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yep.

SHADLE: For God's own purposes.

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: Right, and I know Hart has some arguments against positions like that, that, you know, turns God into a monster, like a moral monster, you know?

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: But I think, you know, something like that is a crucial area of disagreement.

O’NEILL: Yes.

SHADLE: And I also . . . I agree with you also about . . . that universalism maybe has some difficulties with the problem of evil, because if, you know, if God wouldn't willingly permit some people to experience eternal damnation, why does God permit evil at all? Why? Why permit evil to enter into creation at all?

O'NEILL: Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: And I think that's a difficult question. But this this is just a conversation. These are issues that require much more detailed argument.

O’NEILL: Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: But something that also comes to my mind, and this is really difficult to do, but you know earlier you said revelation is the starting point for theology, and one thing, you know, if I was writing a book on this . . . It just seems clear from Jesus's preaching on the Kingdom of God that time is important, that there is an appointed time. And, you know, like the parable of the maidens with the lamps, for example, right? You need to be ready when the time comes.

O’NEILL: Mm hmm.

SHADLE: Right. And that's just emphasized over and over, and you can even go back to the Old Testament, that it's kind of prefigured in this concept of the Day of the Lord, right, that there is a time when judgment comes, and really that's part of the message of revelation. And that's just not really captured in, you know, universalism. And it's sort of like time is dissolved in universalism.

O’NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: You know, however long it takes.

O'NEILL: Yes, exactly. Yeah, yeah.

SHADLE: Yeah. Okay. So, last question. So, if you don't mind sharing. what is a writing project you're working on now?

O'NEILL: Yeah. So, I'm . . . I've been, for a number of years now, slowly, slowly working through a book that’s more or less on what we're talking about right now. It's about sort of laying out, okay, what are the positions that Christians can hold regarding the problem of evil, and especially the problem of damnation, because temporal evils are ended, right, they're ended, but the really difficult question in the problem of evil is the question of hell, because it's unending evil. So, it's a book about laying out what I think are three sort of main positions on that, one of them being the free will defense position, one of them being universalism, particularly hard universalism, and then one of them being the, what I call the broadly Augustinian-Thomistic position.

SHADLE: Okay.

O'NEILL: And just comparing the differences between the three and then ultimately arguing in favor of the Augustinian-Thomistic one and trying to explain, trying to give at least a cursory or as much of an answer as could be given regarding why it is the case, if God could save all, that he doesn’t. So that's a big thing that I've been working on.

SHADLE: Okay. Well, that's going to make a splash, I think.

O'NEILL: I hope so. If I can ever finish it, you know.

SHADLE: Yeah, yeah, that's the key.

O'NEILL: Yeah.

SHADLE: Okay. Well, and also it's . . . What about this Sacra Doctrina and the Sapiential Unity of Theology that you're working on with Joshua Madden. Is that finished yet?

O'NEILL: So that was a . . . it's sort of a . . . Yeah, this was a volume that was supposed to be coming out, and then it was, you know how things go in in academia, something’s going to come out and then it gets sidetracked and whatever. So, yeah. So that's sort of in a no man's land right now. So yeah, so I also have an article on St. Thomas and chance, whether chance is something that can occur given St. Thomas’s view of Providence, and that's in a companion to Providence, the question of Providence in Christian theology that T&T Clark Bloomsbury will be publishing in the future, so I don't know. The nerdier among your fans might, you know, find that as good bedtime material.

SHADLE: No, that's really interesting for the dialogue between faith and science, right.

O'NEILL: Yeah. Yes. Yeah. And that's such a big . . . I mean, it's interesting when you talk about the crest in this interest within the church in Providence and free will and stuff, but that really coincides with outside of the church, this huge influx in interest in like the question of free will and determinism, is so hot in philosophy, even outside of the church. Something's going on. I don't know what it is, something’s in the air that's causing just humans in general to be interested in the question of fate and things like that.

SHADLE: Well, then I'm glad you're going in that direction, too, because then, you know, bringing this more theological conversation into that dialogue between theology and science, I think, is going to be really interesting.

O'NEILL: Yeah, I hope so, yeah.

SHADLE: All right. Well, thank you, Taylor. This has been really, really fun and interesting, and I hope the listeners think so too, but thank you so much for joining me.

O'NEILL: Thank you so much for having me on. This was great. I really had fun.

SHADLE: That was Taylor Patrick O'Neill, and you've been listening to the Window Light podcast. Check out the Window Light newsletter for expert analysis on the fields of Catholic theology and ministry, explorations of historical theology, commentary on current events, and theological and spiritual reflections. You can find it at windowlight.substack.com.

Taylor Patrick O’Neill, Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: A Thomistic Analysis (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2019).

The Catholic University of America, in Washington, DC.

Paul J. Griffiths, “Theological Disagreement: What It Is & How to Do it,” 2014 Catholic Theological Society of America Presidential Address. https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/ctsa/article/download/5502/4984/0

Pope Francis, Apostolic Letter Ad Theologiam Promovendam (2023). https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/it/motu_proprio/documents/20231101-motu-proprio-ad-theologiam-promovendam.html

Actually, the Pontifical Academy of Theology.

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-1988), Swiss Catholic theologian.

Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, O.P. (1877-1964), French Dominican theologian.

Walter M. Miller, Jr., A Canticle for Leibowitz (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1959).

Henri de Lubac, S.J. (1886-1991), French Jesuit theologian.

Marie-Dominique Chenu, O.P. (1885-1990), French Dominican theologian.

Karl Rahner, S.J. (1904-1984), German Jesuit theologian.

Jean Daniélou, S.J. (1905-1974), French Jesuit theologian.

Louis Bouyer, C.O. (1913-2004), French Oratorian theologian, a convert from Lutheranism.

Reinhard Hütter and Matthew Levering, eds., Ressourcement Thomism: Sacred Doctrine, the Sacraments, and the Moral Life (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America, 2010).

Michael Dauphinais was not involved with this particular volume, but has authored and edited several other volumes on Aquinas that could be considered examples of “ressourcement Thomism.”

The Molinists were followers of Luis de Molina, S.J. (1535-1600), who argued that God has knowledge of future contingent events through “middle knowledge,” the knowledge that arises from God having chosen this world from among the infinite possible worlds God could have created. According to Molina, God provides grace knowing through this middle knowledge whether we will freely accept or reject it.

The Prima Pars is the first part of St. Thomas Aquinas’s magnum opus the Summa Theologiae.

Bañezians were followers of Domingo Bañez, O.P. (1528-1604), who argued that God moves the human will to act through what he called “physical premotion.”

Hans Urs von Balthasar, Dare We Hope “That All Men Be Saved”? (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1986).

David Bentley Hart, That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019).