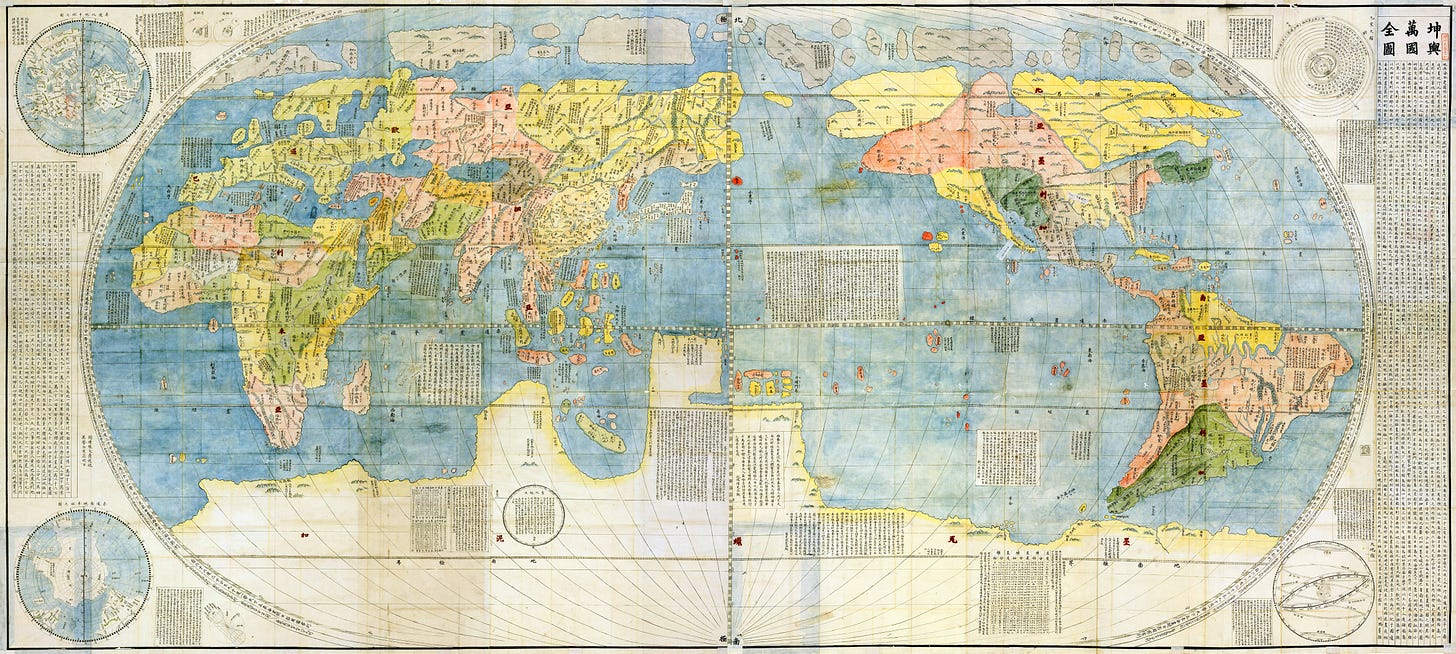

I have been writing about sixteenth and seventeenth-century Jesuits a lot lately. Two weeks ago, I wrote about the struggle to make sense of God’s universal salvific will after the “discovery” of the Americas and the colonization of the indigenous peoples there. Last week I wrote about Matteo Ricci, S.J. and the Chinese rites controversy, the dispute over the place of traditional Chinese religious language and rituals in the practice of Chinese converts to Christianity, pitting Jesuits against the other major missionary orders. Later this week, I will post an interview I had last week with Italian historian Eleonora Rai on the Jesuit theologian Leonard Lessius, who likewise played an important role in the debates over grace during the post-Tridentine period.

I promise this is not becoming a niche newsletter (well, to the extent that Catholic theology is not already niche). I know “baroque” scholasticism is not everyone’s cup of tea. And as I noted a few weeks ago, most of us probably absorbed from our early theological studies the sense that the post-Tridentine period is not really worthy of our interest, representing a period of decline between the High Middle Ages and more recent times.

As I explained at the time, though, I think it is important, perhaps even necessary, to explore this nearly forgotten part of our past to better understand the challenges of the present, most centrally the ongoing dispute over the legacy of Vatican II. One reason I think these recent essays on the baroque Jesuits are worthwhile is because, as different as those theologians are from us, they have something meaningful to tell us about our contemporary confrontation with the reality of religious and cultural pluralism.

Recently, I have been re-reading some of the key works of the contemporary Belgian theologian Lieven Boeve, a professor at KU Leuven (coincidentally, the successor of the University of Leuven, which features prominently in my conversation with Dr. Rai coming later this week). Boeve is one of the most important theologians for my own theological development, and probably the most important I have encountered after my theological education. I drew extensively on his “theology of interruption” in my book Interrupting Capitalism: Catholic Social Thought and the Economy.

In his work, Boeve seeks to overcome the divide between the theologies of continuity and theologies of discontinuity (or rupture) that have emerged since Vatican II through what he calls a “theology of interruption.” Although Boeve’s terminology is similar to that used by Pope Benedict XVI in his famous remarks on the hermeneutics of Vatican II, the former’s meanings are quite different. Theologies of continuity are those theological perspectives that see a fundamental harmony between Christianity and the aspirations of the modern world. Christianity affirms and completes those aspirations. Examples from the Catholic world would include the theologies of Hans Küng, Edward Schillebeeckx, David Tracy, and Karl Rahner (although in my view, and pardon the lame theological humor, Rahner transcends this classification to a certain extent).

Theologies of discontinuity, on the other hand, perceive a radical distance between the distinctive truth claims of Christianity and modernity. This perspective includes various forms of fundamentalism or traditionalism, but also more sophisticated theologies like that of Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI and the Radical Orthodoxy movement. Boeve also links these opposing perspectives to the dispute between the “Chicago school” and the “Yale school”, or theologies of correlation and postliberal theology, that divided American theology in the 1980s and 1990s.

Boeve argues that these dichotomous positions are both premised on a polarity between Christianity and secularism. Theologies of continuity understand themselves as bridges between the Christian tradition and the secular world, affirming secular aspirations and correcting or “demythologizing” aspects of the Christian tradition that contradict them, while critiquing the secular world’s tendency to exclude religious faith, which, in these theologies, qualifies or fulfills secular reason. Theologies of discontinuity, on the other hand, perceive the secularism, absolutized autonomy, and instrumentalization of reason characteristic of modernity as hostile to authentic Christianity. In this view, “Theology ought, therefore, to take the discontinuity between Christian faith and the contemporary context as its point of departure” (Boeve, God Interrupts History, p. 36).

Boeve bluntly points out, however, that this focus on the polarity between Christianity and secularism renders both types of theology irrelevant in the contemporary context. Although secular worldviews are prevalent, secularism is not as pervasive as many twentieth-century sociologists predicted. The contemporary world, at least in Europe, is certainly post-Christian, but it is also post-secular. Boeve points to the growth in New Age movements, individualized bricolages of Christian and other traditions, and immigrant religiosity, especially Islam, as examples of contemporary pluralism:

Christianity has not been replaced by a secular culture, but by a plurality of life options and religions—among which the secularist (atheist) position, in all its variants, is only one—that have moved in to occupy the vacuum left behind as a result of its diminishing impact. (p. 27)

Boeve argues that the fundamental reality of contemporary Europe is not secularism per se, but rather detraditionalization, the disappearance of the Christian way of life as a given:

Traditions no longer automatically steer this construction process [i.e., of personal identity], but are only possibilities together with other choices from which an individual must choose. One single determined tradition is no longer unquestioned or taken to be of decisive importance. . . . Every choice has its alternatives in relation to which one must answer for one’s options. At the same time, those who opt for classical or traditional identities are also making a choice. (p. 22)

I think the situation in the United States could likewise be characterized as detraditionalized and post-secular, even if the landscape is somewhat different than in Europe. Christianity continues to have a powerful, although diminishing, hold on culture. A significant fraction of American Christians, reacting strongly against detraditionalization and pluralism, have adopted a conservative form of the faith, sometimes mixed with political nationalism. Although a growing number of Christians identify as atheist or agnostic, as in Europe, New Age beliefs and practices are prevalent, as are adults who identify as “spiritual but not religious.” Other religions such as Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism, likewise claim space in the public sphere.

One thing I value about Boeve’s work is its nuance. For example, although he argues that the contemporary world is post-secular, he recognizes that there are pervasive secularizing tendencies. For example, he notes that religious and cultural pluralism exists in tension with the pervasiveness of global capitalism, and that capitalism provides a ready-made way of making sense of religious pluralism: as a marketplace of religions and spiritualities. The market mentality tempts us to think of religion and spirituality through the lens of consumerism, as a consumer choice customized to our preferences, while encouraging a kind of practical atheism in our lifestyles.

A related challenge characteristic of contemporary pluralism is the tendency to functionalize religion. This is the temptation to treat religion as a means to some other end:

[T]he Christian tradition is in danger of becoming little more than a reserve supply of narratives and rituals, side by side with other narratives and rituals, which can be used as a resource in the construction of personal religious identity and in the individual search for spirituality. (p. 29)

Boeve seems to have something like spiritual “self-help” in mind here, but I think religion can also play a functional role in the construction of social identity, as well, for example in different types of Christian nationalism.

Finally, a third challenge arises from resistance to pluralism and detraditionalization:

Others feel extremely uncomfortable with this reflexivity, and turn more to traditionalist and fundamentalist positions, stringently reinforcing the bond between social and individual social identity and the tradition transmitted from the past. (p. 29)

Although rising out of opposition to pluralism and detraditionalization, religious traditionalism undoubtedly engages in its own form of bricolage in its approach to tradition, and can likewise at times instrumentalize religion, for example in the intertwining of fundamentalism and Christian nationalism noted earlier.

Although pluralism renders both theologies of continuity and discontinuity irrelevant, Boeve argues that the former correctly recognizes that the Christian faith must be sensitive to its historical context:

[I]t actually makes a difference for the Christian faith to be involved with the context, and indeed that there is an intrinsic link between the significance of revelation, faith, church, and tradition, and the context in which they are given form. Faith and church are not in opposition to the world, they participate in constituting the world and, furthermore, they are in part constituted by the world. Given the fact that God reveals Godself in history and that it is precisely in history that God can be known by us, history ultimately becomes co-constitutive of the truth of faith. (p. 7)

On the other hand, today there is no longer a one-to-one correlation between faith and context: “[T]here is no longer an easily identifiable secular culture to which Christian faith is related and in which Christians live their faith. Theology is no longer engaged in a dialogue between two partners but immersed in a dynamic, irreducible, and often conflicting plurality of religions, worldviews, and lifeviews” (p. 34).

Boeve also rejects the attempts made by some theologies of continuity to, in effect, circumvent pluralism:

Any attempt to denote religious plurality by way of a meta-discourse and to transcend the conflict of truth claims by way of a universal epistemological framework does not take the radicality of these truth claims seriously. Such an epistemological observer’s position is and remains totalizing; the confrontation with the other, with difference, is ultimately done away with. (p. 44)

This leads to the heart of Boeve’s theological project:

If one analyzes the many ways of living, thinking, and acting, the many religions and fundamental life options, in terms of radical plurality, then, the first and irreducible level of our reflection is our particularity itself. The starting point is thus the specific narrativity of a fundamental life option whether religious or not, [at] the level of the concrete particular narrative. (p. 39)

In terms of the Christian faith, this means that “Paying greater attention to the irreducible particularity of the Christian narrative is one of the lessons learned from the encounter with the plurality of religions and fundamental life options” (p. 52)

Echoing postliberal theologians like George Lindbeck or Stanley Hauerwas, Boeve continues:

The Christian narrative forms its own (albeit dynamic) symbolic space, its own hermeneutical horizon, i.e., its own hermeneutical circle. Becoming acquainted with Christianity is thus something like learning a language, a complex event that presupposes grammar, vocabulary, competence, and familiarity, as much as it does empathy. (p. 52)

Christians ought to engage the world in and through the particularity of the Christian tradition, not through trying to somehow slip outside of it to find something more universal.

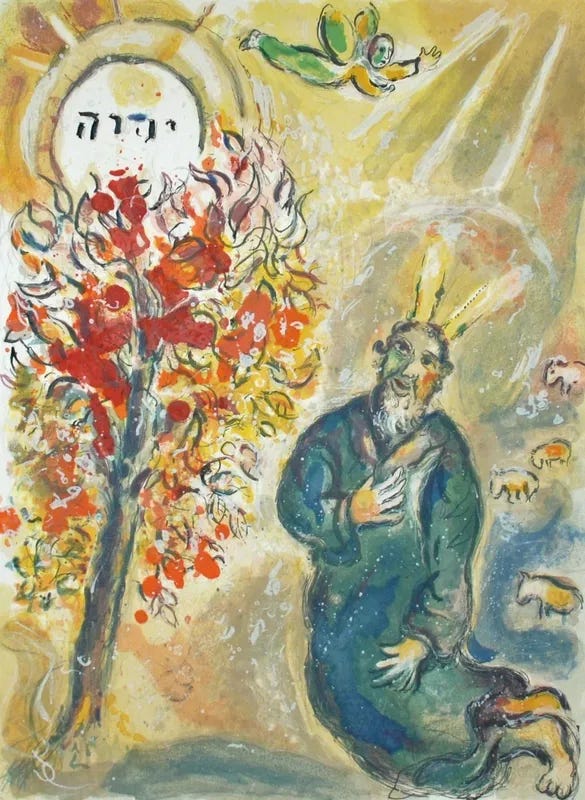

Where Boeve departs from earlier postliberal theologians is his introduction of the concept of “interruption.” Before defining the term, it is important to point out that Boeve sees “interruption” as a theological category or pattern. It “structures the way in which we reflect upon the relationship in which God is engaged with God’s creation” (p. 45), as expressed in both the Old and New Testaments.

Here is how he defines it:

[T]he category of interruption holds continuity and discontinuity together in an albeit tense relationship. Interruption is after all not to be identified with rupture, because what is interrupted does not cease to exist. On the other hand, it also implies that what is interrupted does not simply continue as though nothing had happened. Interruption signifies an intrusion that does not destroy the narrative but problematizes the advance thereof. It disturbs the anticipated sequence of sentences following one after the other, and disarms the security devices that protect against disruption. Interruption refers to that “moment,” that “instance,” which cannot occur without the narrative, and yet cannot be captured by the narrative. It involves the intrusion of and otherness that only momentarily but nonetheless intensely halts the narrative sequence. Interruptions cause the narrative to collide with its own borders. They do not annihilate the narrative; rather, they draw attention to its narrative character and force an opening toward the other within the narrative. (p. 42)

There is a lot to unpack here! What I take from this is that the Christian narrative itself tells us that, through our encounter with the Other, our understanding of, and experience of, that narrative is forever transformed, but in a way ultimately consistent with the narrative. I think it is also helpful here if we think of “narrative” both in terms of the collective Christian tradition and the individual Christian’s personal narrative or self-understanding.

In an absolute sense, the Other, the Interrupter, is God. The Christian narrative, which ultimately has God as its source, tells us that God, in a sense, transcends the narrative; therefore our ongoing experience of God, although it comes in and through the Christian narrative, also provides a dynamism that transforms our understanding of that narrative and bringing us closer to God. And just to reiterate, even though God transcends the Christian narrative, we Christians do not (well, maybe, but not in the same way), and therefore the experience of interruption is not something that comes from stepping outside that tradition, but rather through our immersion in it.

Boeve goes further, however, suggesting that the Christian narrative, rooted in the Scriptures, likewise tells us that we often encounter God through those who do not share our narrative. This can include the religious Other. It is this aspect that Boeve finds particularly relevant in the contemporary context:

It is through the encounter with concrete others and otherness that the Christian narrative is challenged and interrupted. It is such interruption that has the potential to become the locus in which God is revealed to Christians today. (p. 48)

We also encounter God through those who are excluded, oppressed, or marginalized, whom Boeve describes as the victims of “closed” or “totalizing” narratives (p. 48). This encounter, which we experience as an interruption, then calls Christians to deepen their own understanding of their faith and interrupt those narratives that victimize the oppressed. Boeve is clearly drawing on the German theologian Johann Baptist Metz’s notion of the dangerous memory of history’s victims, and there are also some interesting overlaps here with, for example, Ignacio Ellacuría’s description of the poor as the Crucified People, a locus of Christ’s presence in the world but also agents of salvation in the world, that are worth exploring.

I think Boeve’s notion of a closed or totalizing narrative, which he borrows from the postmodern philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, is an especially fruitful one. For example, he argues that social systems, such as the global capitalist economy, can become totalizing narratives that victimize the oppressed (I think there’s a connection here with my discussion of reductionism in relation to intersectional theology here). But he also notes that the reduction of Christianity to the therapeutic or to the consumeristic is likewise a type of closed narrative that Christians ought to “interrupt” (p. 44). And, perhaps most interesting of all, he explains that the Christian narrative itself faces the risk of closing in on itself, of excluding the plural, the contingent, the ambiguous, in a premature quest for certitude and security.

There is certain a strong case in support of Boeve’s claim that the concept “interruption” describes an important structural element of God’s relationship with creation in the Christian narrative. Most importantly, as Boeve recognizes, the central Christian doctrine of the Incarnation can be understood as the interruption of God in history, a fundamental re-orientation of our understanding of what it means to be human. But a number of other theological dynamics, many of which have been central to contemporary Catholic disputes, can be understood in terms of the structure of interruption: nature and grace, faith and reason, Church and world, human and divine agency, etc.

To bring things home, I think there are at least two reasons why exploring the theological disputes that engaged the Jesuit theologians in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are relevant for the contemporary context described by Boeve. For one, these theologians were wrestling with the question of pluralism and the encounter with the religious Other in a way analogous to our own experience. Even though these theologians and missionaries were formed in a Christian cultural matrix, the encounter with the indigenous peoples of the Americas and the deepening relationship with the nations of Asia made pluralism an important part of their theological and social context.

In fact, their theological wrestling loosely follows the pattern of an interruption outlined by Boeve. For one, the encounter with the Other led these theologians to question certain aspects of their inherited tradition regarding the salvation of non-Christians and the salvific value of non-Christian religious and cultural practices. Second, it was the Christian narrative itself that led them to both the encounter with the Other and their wrestling with the tradition, namely the missionary impulse (Mt. 28:19) and the affirmation of God’s universal salvific will (1 Tim. 2:4). Third, their encounter with the Other led to a re-formulation of the Christian narrative and the role of non-Christians in that narrative, for example, Francisco Suarez and Juan de Lugo’s theory of “implicit faith,” Matteo Ricci’s account of Confucianism as a “natural religion” compatible with Christianity and the Jesuit figurists’ narrative of a cross-cultural, primitive revelation.

We can also see some of the tensions identified by Boeve in these disputes, particularly the Chinese rites controversy. For example, as I noted last week, the Franciscan and Dominican critics of the Jesuits criticized the latter essentially for creating what Boeve calls a “meta-discourse” regarding Chinese religion, glossing over its concrete particularities and complex history. For their part, the Franciscans and Dominicans arguably failed to experience the encounter with the Chinese as an interruption, instead interpreting the experience in the closed terms of the existing Christian narrative.

It is also important to point out that all of these European theologians and missionaries, both the Spanish Dominican and Jesuit theologians who debated the salvation of the indigenous peoples of America and the missionaries to China, were to one degree or another shaped by the totalizing narratives that constituted European colonialism, although one could argue that many of them challenged those narratives, as well.

The second reason I think the baroque Jesuits and Boeve’s theology can be fruitfully juxtaposed is that, as I noted, fundamental to Boeve’s theology is the insight that pluralism has replaced secularism as the dominant characteristic of the contemporary context. The Jesuits, on the other hand, were wrestling with the theological question of pluralism at the very beginnings of the emergence of secularism. For example, the Chinese rites controversy, particularly once the debate moved to Europe, played an important role in the emergence of the modern notion of “religion” as a cross-cultural phenomenon, distinct from other spheres of social life, an important development in the process of secularization. This suggests that we shouldn’t just think of pluralism as a stage succeeding secularism, but rather think of pluralism and secularization as intertwined in a deep history worthy of theological exploration.

Of Interest…

As the Catholic News Agency reports, the state of Oklahoma has approved the first religious charter school, a Catholic school named St. Isidore of Seville Virtual School. This means that public funds will help students pay the tuition for attending the school. I think this is an important and interesting issue, and one on which Catholics are likely to be of different minds. The US Catholic bishops have long argued for what could be called a “pluralistic” school system, in which religious schools receive public funding. There are good reasons, both theological and social, for supporting a more pluralistic school system. The theologian John Courtney Murray, S.J. argued for such a system in his 1962 essay “Federal Aid to Church-Related Schools.” Religious schools contribute to the common good in the same way that public schools do. Likewise, education is not just a question of subject matter, but of addressing the whole person. If (see above) we believe that our society is pluralistic, with competing notions of what it means to be a flourishing person, then perhaps we should allow diverse groups to contribute to the common good through educational programs consistent with their values, while avoiding some of the “culture war” battles regarding public schools? Of course, the public schools remain one of the most important venues where we encounter the religious or cultural Other, and so perhaps one could argue that the value of public schools is not so much that they are secular but that they are pluralistic. But in the supposedly “neutral” setting of public schools, will pluralism be reduced to the “cultural eclecticism” that Pope Benedict XVI warned about in his encyclical Caritas in Veritate, in which differences are recognized, even celebrated, but stripped of any deeper significance, a danger very much similar to the functionalization criticized by Boeve? Another problem is that of equity. Private schools are often out of reach for poor children, and even in states with charter schools or vouchers for private schools, poorer families still often only have access to lower-quality public schools. If an authentically Catholic response to the schools question embraces some form of pluralism, it ought to likewise promote greater equity and access to quality education.

Coming Soon…

As I noted above and in earlier posts, on Friday I will publish my interview with Dr. Eleonora Rai, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Turin, in which we discuss her work Leonard Lessius, S.J., a pivotal theologian in the post-Tridentine era. We had a great conversation, and Dr. Rai is very engaging, so be sure not to miss it.

We are in the midst of conference season for Catholic theologians in the United States. The College Theology Society just met in Fairfield, Connecticut, the Academy of Catholic Hispanic Theologians of the United States (ACHTUS) is currently meeting in New Orleans, and the Catholic Theological Society of America meets this weekend in Milwaukee. And I am not able to attend any of them! Considering this is supposed to be a newsletter reporting on the field of theology, I will try to find a way to include some commentary on these conferences, so stay tuned.