Salvation Outside the Church: The Development of a Doctrine

Or, Chasing a Troll Through the Centuries

Last week, you may remember, I wrote about the ecumenical milestone of Pope Francis including a group of Coptic Orthodox martyrs murdered by ISIS in Libya in 2015 in the Roman martyrology. For my troubles, an individual on social media accused me of “dabbling in heresy, schism, and apostasy” for suggesting in the article that the Coptic Orthodox could be among the saved, and claimed that Pope Francis’s gesture was “further prove [sic] that the Vatican II sect is the end-times Counter Church, the Whore of Babylon.”

In the spirit of Joseph the patriarch—”Even though you meant harm to me, God meant it for good, to achieve this present end” (Gen. 50:20)—rather than “feeding the trolls” by hashing things out on Twitter, I thought it would be a good opportunity to explore the development of the doctrine of extra ecclesiam nulla salus (“outside the Church there is no salvation”), which I only briefly touched on in the previous article, in more detail.

The reason I am excited about the opportunity provided by my online friend’s response is because the development of the Catholic Church’s teaching on the question of the salvation of non-Catholics (and non-Christians) is a perfect, clear-cut example of the phenomenon I pointed out in an earlier post on the hermeneutics of Vatican II: debates about whether Vatican II was in continuity with the Church’s tradition or a rupture from it often hinge on ignorance of that pre-conciliar tradition. I concluded:

[W]ith a better understanding of the complexity and diversity of Catholicism from roughly the Renaissance era onward, we can get a clearer sense of how Vatican II represented authentic developments in the Church’s teaching and practice even while seeming like a rupture to those who experienced it.

Vatican II truly did represent something new in its teaching on the salvation of non-Catholics and non-Christians in documents like Nostra Aetate, Unitatis Redintegratio, and Lumen Gentium. This teaching is commonly perceived as a rupture with the Church’s earlier teaching that “outside the Church there is no salvation,” many taking this rupture to mean that we can ignore earlier teaching and theologies of salvation as products of a benighted age, and a much smaller minority (like my friend) seeing this as evidence of the perversity of the “Vatican II sect.” A closer look at theological developments in the preceding centuries, starting particularly in the sixteenth century, show, however, that theologians, and even the Church’s Magisterium, gradually taking a position very close to that eventually adopted at Vatican II.

Francis Sullivan in his Salvation Outside the Church?: Tracing the History of the Catholic Response (Paulist, 1992) and Ilaria Morali’s chapters in Catholic Engagement with World Religions: A Comprehensive Study (Orbis, 2010) provide indispensable histories of these developments, and I rely on their work in this article. As helpful as they are however, these works only scratch the surface, and quite a bit more work is needed to fully understand these developments.

When my trollish friend accused me of dabbling in heresy, I pointed him to some citations from Popes Pius IX (1792-1878) and Pius XII (1876-1958), suggesting that the notion that salvation was a possibility for those who are not explicitly Catholic is a pre-conciliar teaching of the Magisterium. My friend, in turn, sent me a video purportedly explaining why the teachings of those two popes did not mean what to all appearances they seemed to say.

The key text from Pius IX comes from his 1863 encyclical Quanto Conficiamur Moerore (italics added by me for emphasis):

Here, too, our beloved sons and venerable brothers, it is again necessary to mention and censure a very grave error entrapping some Catholics who believe that it is possible to arrive at eternal salvation although living in error and alienated from the true faith and Catholic unity. Such belief is certainly opposed to Catholic teaching. There are, of course, those who are struggling with invincible ignorance about our most holy religion. Sincerely observing the natural law and its precepts inscribed by God on all hearts and ready to obey God, they live honest lives and are able to attain eternal life by the efficacious virtue of divine light and grace. Because God knows, searches and clearly understands the minds, hearts, thoughts, and nature of all, his supreme kindness and clemency do not permit anyone at all who is not guilty of deliberate sin to suffer eternal punishments.

Also well known is the Catholic teaching that no one can be saved outside the Catholic Church. Eternal salvation cannot be obtained by those who oppose the authority and statements of the same Church and are stubbornly separated from the unity of the Church and also from the successor of Peter, the Roman Pontiff, to whom “the custody of the vineyard has been committed by the Savior.” . . .

Here, in the second paragraph, Pius IX affirms the traditional teaching that there is no salvation outside the Catholic Church, headed by the pope. In the preceding paragraph, however, Pius seems to make an exception for individuals with three characteristics: 1) they are in a state of invincible ignorance regarding the Catholic religion; 2) they sincerely observe the natural law, i.e., the moral precepts known through human reason; and 3) they are “ready to obey God.” Pius seems to suggest that individuals who meet those three conditions are, through the mysterious grace of God, “able to attain eternal life.”

The aforementioned video, however, argues that this is a misreading of Pius. Quite reasonably, it suggests that when he refers to the “virtue of divine light,” this is a reference to the supernatural virtue of faith. But, so the video argues, the supernatural virtue of faith requires explicit fidelity to the teachings of the Catholic Church. Therefore, although the passage is worded awkwardly, Pius must be taken to mean (again, in the interpretation of the video) that those individuals who meet those three criteria will be infallibly led by God to the Catholic Church.

Although this interpretation is not outlandish, it goes against the plain meaning of the text, a problem the video sheepishly admits. Second, if Pius meant what the video claims, the following sentence, regarding God searching and knowing “the minds, hearts, thoughts, and nature of all,” would hardly be necessary. So this strict reading of Pius is unconvincing.

Even if we do read Pius as teaching that at least some people formally outside the Catholic Church can be saved, the passage still leaves some important questions unanswered. What does it mean for those who are not explicitly Christian to have “the divine light” of faith? And how can the first paragraph be reconciled with the second? Here is where knowledge of theological debates from the preceding centuries is crucial.

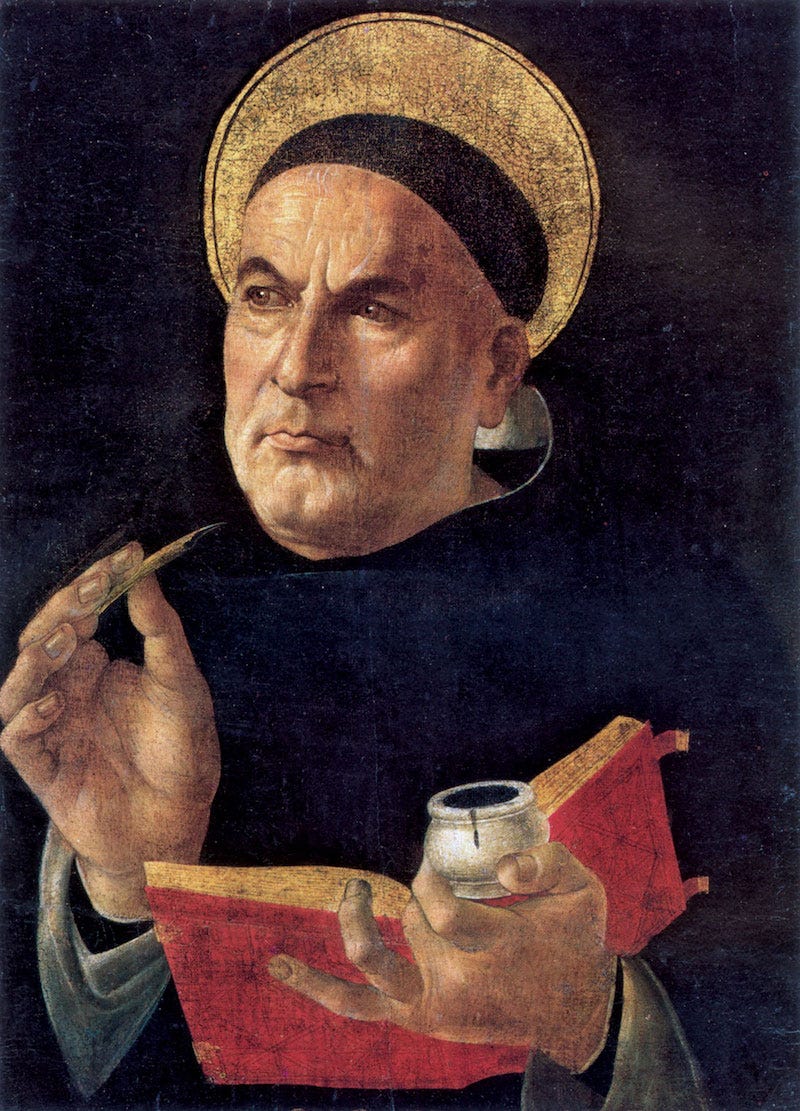

The aforementioned video turns to St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) as an authority for interpreting Catholic teaching on the issue. Of course, Aquinas interprets the teaching that there is no salvation outside the Church in a quite straightforward sense. For example, in the Summa Theologiae, Aquinas writes:

After grace had been revealed [i.e., after Christ’s mission was complete], both learned and simple folk are bound to explicit faith in the mysteries of Christ, chiefly as regards those which are observed throughout the Church, and publicly proclaimed, such as the articles which refer to the Incarnation . . . (ST, II-II, q. 2, a. 7)

Similarly, regarding baptism:

Men are bound to that without which they cannot obtain salvation. Now it is manifest that no one can obtain salvation but through Christ . . . But for this end is Baptism conferred on a man, that being regenerated thereby, he may be incorporated in Christ, by becoming His member . . Consequently it is manifest that all are bound to be baptized: and that without Baptism there is no salvation for men. (ST, III, q. 68, a. 1)

Aquinas’s thought is more nuanced, however. For example, he explains that the Israelites of the Old Testament had an implicit faith in Christ and his salvific mission:

[A]ll the articles [of faith] are contained implicitly in certain primary matters of faith, such as God's existence, and His providence over the salvation of man, according to Hebrews 11: "He that cometh to God, must believe that He is, and is a rewarder to them that seek Him." For the existence of God includes all that we believe to exist in God eternally, and in these our happiness consists; while belief in His providence includes all those things which God dispenses in time, for man's salvation, and which are the way to that happiness: and in this way, again, some of those articles which follow from these are contained in others: thus faith in the Redemption of mankind includes belief in the Incarnation of Christ, His Passion and so forth.

Accordingly we must conclude that, as regards the substance of the articles of faith, they have not received any increase as time went on: since whatever those who lived later have believed, was contained, albeit implicitly, in the faith of those Fathers who preceded them. But there was an increase in the number of articles believed explicitly, since to those who lived in later times some were known explicitly which were not known explicitly by those who lived before them. . . . (ST, II-II, q. 1, a. 7)

Although this concept of implicit faith was primarily developed to explain the relationship between the Old and New Covenants, he also uses it to explain the salvation of righteous Gentiles before the coming of Christ:

If, however, some [Gentiles] were saved without receiving any revelation, they were not saved without faith in a Mediator, for, though they did not believe in Him explicitly, they did, nevertheless, have implicit faith through believing in Divine providence, since they believed that God would deliver mankind in whatever way was pleasing to Him, and according to the revelation of the Spirit to those who knew the truth. (ST, II-II, q. 2, a. 7, ad 3)

That being said, Aquinas does not appeal to this theory of implicit faith in regards to the salvation of non-Christians after the coming of Christ. He assumes that the Muslims, Jews, and heretical Christians of the medieval world he knew were adequately familiar with the Gospel that they could be considered to have rejected it (see Sullivan, pp. 51-55 and Morali, pp. 65-68 for a more detailed analysis of Aquinas’s evolution on this last issue). Aquinas’s teaching (for better or worse) became the starting point for later theological reflection on the question of salvation for non-Christians, to which we now turn.

In addition to Aquinas, the aforementioned video also turns to the sixteenth-century Spanish theologian Francisco de Vitoria, O.P. (1493-1546) as an authoritative voice on this question. A disciple of Aquinas teaching at the University of Salamanca, Vitoria largely mirrors the conclusions of Aquinas. Vitoria’s views are especially significant, however, because he was writing just as the Spanish conquest of the Americas was unfolding. In his writings, Vitoria not only responded to the injustices being conducted by the Spanish in the name of Christ, but also to the question of how the indigenous Americans, oblivious to the Gospel for centuries after the coming of Christ, could be saved, given their “invincible ignorance”?

Vitoria writes:

When we postulate invincible ignorance on the subject of baptism or of the Christian faith, it does not follow that a person can be saved without baptism or the Christian faith. For the aborigines [sic] to whom no preaching of the faith or Christian religion has come will be damned for mortal sins or for idolatry, but not for the sin of unbelief. (De Indis et de Iure Belli Relectiones, cited in Sullivan, p. 70)

Vitoria concludes that although the indigenous people cannot be faulted for their lack of faith, they will nevertheless be damned for the mortal sins they have inevitably committed without the assistance of faith or divine grace. As Sullivan notes, Vitoria does not adequately explain how this situation is compatible with God’s universal salvific will (p. 73).

Nevertheless, in his considerations of these questions, Vitoria does pay much more attention to the subjective reception of the Gospel than Aquinas and most other medieval thinkers had. For example, in the Spanish colonies, the friars may have “preached the Gospel” by proclaiming Christian doctrines in a perfunctory way, with little explanation. Could those indigenous peoples unswayed by this preaching be considered to have rejected the Gospel? Vitoria thought not. More importantly, he considered that the unjust behaviors of the conquistadores undermined the reception of the Gospel by the indigenous:

[I]t does not appear that the Christian religion has been preached to [the indigenous] with such sufficient propriety and piety that they are bound to acquiesce in it, even though many religious and other ecclesiastics seem both by their lives and example and their diligent preaching to have bestowed sufficient pains and industry in this business, had they been hindered therein by men who were intent on other things. (De Indis et de Iure Belli, cited in Sullivan, pp. 72-73)

These sorts of subjective considerations would be essential to all later Catholic thinking on the salvation of non-Christians.

Although Vitoria did not hold out much hope for this indigenous who had not heard the Gospel, the same was not true for his slightly younger colleagues at Salamanca: Melchior Cano, O.P. (1509-1560), Domingo Soto, O.P. (1494-1560), and Andreas de Vega, O.F.M. (1498-1549). All three, drawing on medieval scholastic conclusions, argued that even those indigenous peoples who had not heard the Gospel could live their life in accord with the natural law, with the assistance of God’s grace. Cano concluded that someone who lived such a life could experience justification, that is, the gracious remission of original sin, and develop implicit faith (this conclusion was based on Cano’s interpretation of an somewhat obscure passage from Aquinas’s Summa; see ST, I-II, q. 89, a. 6). Without explicit faith in Christ, however, this person could not experience salvation. (On Cano, see Sullivan, pp. 74-75 and Moralis, p. 78)

Soto and Vega, who played important roles as theological advisors at the Council of Trent, went a step further than Cano. Soto, in the first edition of his work De Natura et Gratia (1547), argued that for those in a state of invincible ignorance regarding the Gospel of Christ, belief in that which is naturally knowable about God through reason was sufficient for salvation, in place of supernatural faith. Vega, the Franciscan, took a similar position (although Morali’s account of Vega’s thought is unclear; see pp. 77-78). Morali argues that Vitoria had likewise taken this position by the end of his life, developing it in an unfinished section of his De Indis et de Iure Belli (pp. 75-76). By 1549, Soto had concluded that supernatural faith was necessary for salvation; unlike Cano, however, he argued that implicit faith (or fides confusa) was sufficient not only for the justification, but also for the salvation, of those in a state of invincible ignorance regarding the Gospel. Therefore, Soto extended Aquinas’s thinking on the implicit faith of the righteous Gentiles of the past to those in a state of invincible ignorance after the coming of Christ (On Soto, see Sullivan, pp. 75-76 and Morali, pp. 76-77).

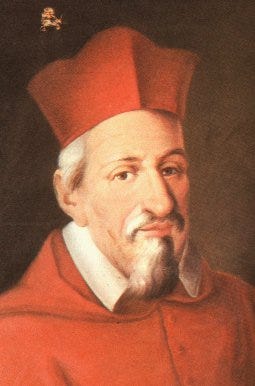

Among the Jesuits, Francisco Suarez (1548-1617) and Juan de Lugo (1583-1660) took positions similar to that of the later Soto, arguing that those in a state of invincible ignorance could be saved through supernatural, though implicit, faith (On Suarez, see Sullivan, pp. 91-94 and Morali, pp. 81-83). De Lugo is also noteworthy for arguing that the Jews, Muslims, and Protestants of the European world could conceivably be in a state of invincible ignorance regarding Catholic teaching, extending Vitoria’s teaching on the subjective reception of Church teaching (Sullivan, pp. 94-98).

Suarez and de Lugo also play an important role by returning the discussion to the question of the role of the Church in salvation. For example, Suarez writes:

. . . [N]o one can be saved who does not enter this church of Christ either in reality [in re] or at least in wish and desire [in voto]. . . . Now it is obvious that no one is actually in this church without being baptized, and yet he can be saved, because just as the desire of baptism can suffice, so also the desire of entering the church. Now we are saying the same thing with regard to anyone who has faith in God, and sincere repentance for sin, but who is not baptized, whether he has arrived at explicit or only implicit faith in Christ. For, with implicit faith in Christ he can have an implicit desire for baptism, which St. Thomas teaches can suffice. (De Fide Theologica, disp. 12, sect. 4, n. 22, cited in Sullivan, p. 93)

In other words, with implicit faith in Christ comes an implicit desire for baptism, and therefore implicit membership in the Church. Similarly, de Lugo:

The possibility of salvation for such a person [i.e., a non-Christian with supernatural, yet implicit, faith] is not ruled out by the nature of the case; moreover, such a person should not be called a non-Christian, because, even though he has not been visibly joined to the church, still, interiorly he has the virtue of habitual and actual faith in common with the church, and in the sight of God he will be reckoned with the Christians. (De virtute fidei divinae, disp. 12, no. 104, cited in Sullivan, p. 97)

With de Lugo, we are not very far at all from Karl Rahner’s theory of the “anonymous Christian” or the teaching of Nostra Aetate.

It is worth noting that the earlier Jesuit Francisco Toledo (1552-1596) proposed a quite different, more legalistic, theology of salvation. According to Toledo, the sacraments are the “ordinary means” of salvation (de lege ordinaria). God, however, can save in ways other than the sacraments. Toledo also emphasized the importance of the promulgation of the requirement of baptism for salvation—baptism is a requirement only to those to whom this law has been promulgated. (See Morali, pp. 80-81)

This approach would be taken up by later theologians. For example, in the nineteenth century, Giovanni Perrone, S.J. argued that the requirements of explicit faith and baptism for salvation were only required for those to whom the Gospel had been sufficiently promulgated. Furthermore, there was not a single moment at which the Gospel was promulgated to the world; rather, the moment of promulgation is relative to time and place, and even to subjective experience (a nod to Vitoria’s insights). Invincibly ignorant non-Christians were simply not bound by these requirements for salvation, and God could save them in other ways. (See Sullivan, pp. 108-12)

Sullivan correctly notes that there is a significant difference between Perrone’s theory, in which the connection between the Church and baptism on the one hand, and salvation on the other, is purely extrinsic, and that of Suarez and de Lugo, for whom there is a more intrinsic relation between them (pp. 109-10). Like Suarez and de Lugo, however, Perrone does insist that non-Christians must have a supernatural, implicit faith to be saved.

We have come full circle, then. Sullivan argues, based on textual evidence, that Perrone helped Pius IX write Quanto Conficiamur Moerore (see p. 116). Whether or not that is so, it is clear that Pius’s statement from that encyclical, cited above, includes elements of both the Suarez/de Lugo and Perrone theories. When he, at first glance paradoxically, refers to the “virtue of divine light” possessed by some in “invincible ignorance about our most holy religion,” he is clearly referring to what the theologians called supernatural, implicit faith, an idea that by that point had a centuries long tradition and roots in Thomistic thought.

Pope Pius XII further develops this teaching, both in Mystici Corporis Christi (1943), where he teaches that at least some non-Catholics “by an unconscious desire and longing . . . have a certain relationship with the Mystical Body of the Redeemer” (no. 103) and in his condemnations of the Feeneyite heresy (1949), where he states:

[F[or a person to obtain his salvation, it is not always required that he be de facto incorporated into the Church as a member, but he must at least be united to the Church through desire or hope.

However, it is not always necessary that this hope be explicit as in the case of catechumens. When one is in a state of invincible ignorance, God accepts an implicit desire, thus called because it is implicit in the soul's good disposition, whereby it desires to conform its will to the will of God.

Through Pius XII’s teaching, then, the Magisterium has affirmed the insights of theologians like Suarez and de Lugo who balanced God’s universal salvific will and the intrinsic connection between the Church, baptism, and salvation, without denying the insights of the more extrinsicist, legalistic approach.

The theologians who had a significant impact on Vatican II’s teaching on grace and salvation—most especially Karl Rahner, S.J., but also Henri de Lubac, S.J., Jean Danielou, S.J., and others—did not, therefore, break with tradition. Rather, they took up a longstanding tradition and offered their own insights as a way to resolve questions left unanswered by that tradition, thus moving the tradition forward. As I noted at the outset, I think this is a good example of how a careful examination of the theological tradition can complexify the dichotomy between continuity and rupture in our understanding of Vatican II. And I am grateful to the anonomous internet troll for the inspiration to make this case!

Coming Soon…

If you are hungry for more on post-Reformation debates about grace and salvation, next week I am interviewing Eleonora Rai, an assistant professor of history at the University of Turin (Italy) and a research associate at KU Leuven, on her work on the sixteenth-century Flemish theologian Leonard Lessius (1554-1623) and his theology of grace and salvation. Lessius was a contemporary of his fellow Jesuits like Francisco Suarez, Francisco Toledo, and Robert Bellarmine, and was involved in some of the same debates over grace and salvation discussed here. I am excited about this interview, which should be published some time in the week after next.

Speaking of exciting interviews, late this week I am interviewing Becket Gremmels, System Vice President for Theology and Ethics at CommonSpirit Health, a network of Catholic healthcare providers. This interview should be published some time next week, and will focus on the role of ethics in a Catholic healthcare system and some of the challenges faced by Catholic ethics professionals in healthcare today.

I'm always happy to see Catholic.theologians writing about this important subject!

Learned quite a bit about the history of grace and salvation, particularly by lesser-known writers who wrote at the same time as "the usual suspects."