Intersectionality and Theology: Risk of Reductionism?

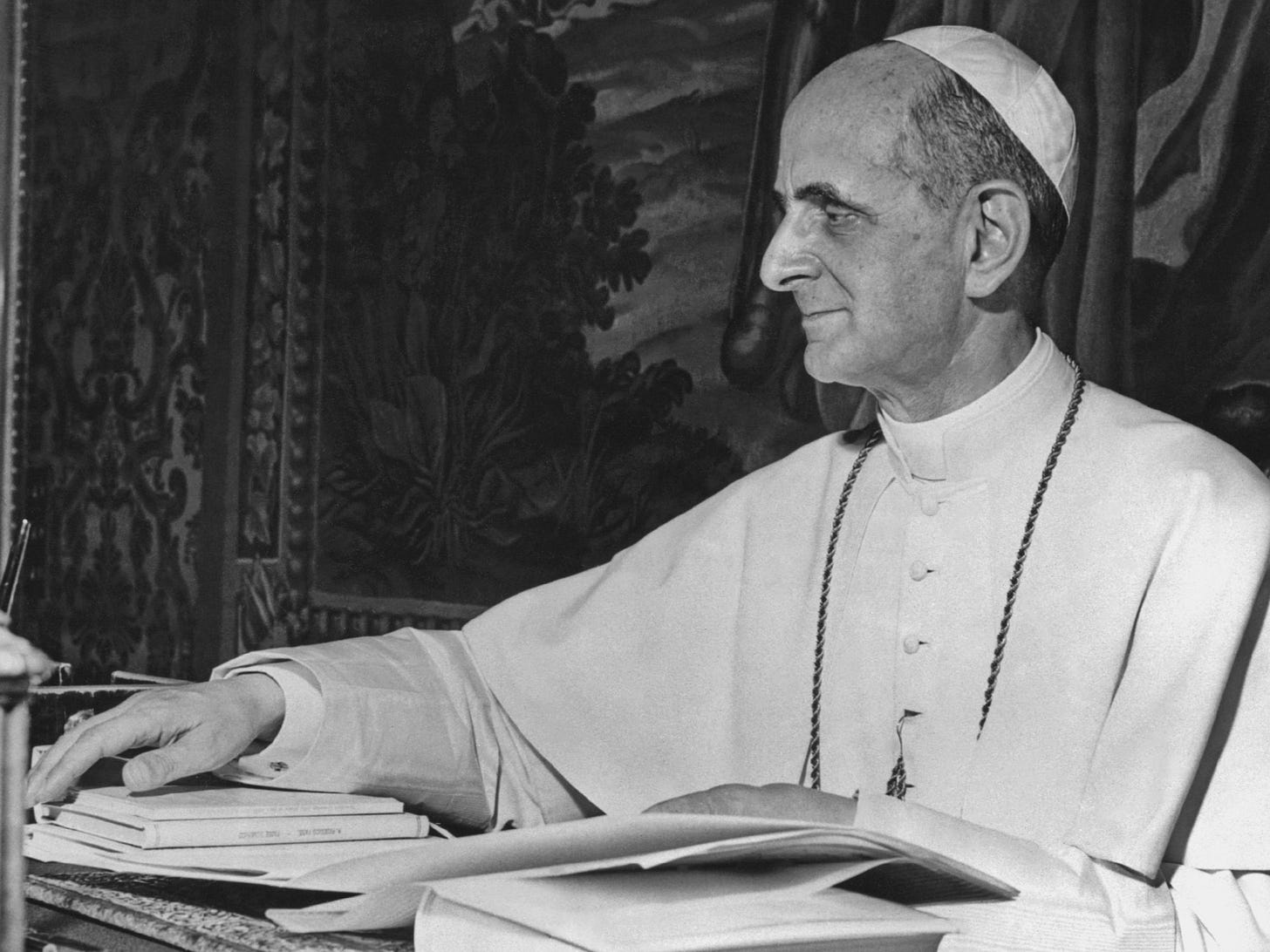

Insights from Paul VI; Plus Just War in Ukraine?

Earlier this week at the Catholic Moral Theology blog, I posted a response to Hoon Choi’s essay “The Case for Intersectional Theology: An Asian American Catholic Perspective,” and since then I have been trying to read through the other articles in the Journal of Moral Theology’s special issue on intersectionality and theology, where Choi’s article was published. So intersectionality and its role in theological method have been on my mind. As I noted in my post, the value of intersectional analysis (and similar methodologies), and how it should be used in theology, is “undoubtedly one of the central debates over theological method today.” In this post I want to examine the question of whether intersectional analysis introduces a kind of reductionism into theological method, and I turn to Pope Paul VI for some insights.

First, what do I mean by intersectionality? The co-editors of the JMT’s special issue—Meghan Clark, Anna Kasafi Perkins, and Emily Reimer-Barry—in their introduction, draw on a definition from Kimberlé Crenshaw, the legal scholar who first used the term: “a metaphor for understanding how multiple forms of inequality or disadvantage sometimes compound themselves” (cited on pp. 6-7). Those “forms of inequality or disadvantage” could include social class, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, and sexual identity, among others.

As Clark, Perkins, and Reimer-Barry explain, one way that intersectional analysis can be used in theology is to identify and challenge the ways these intersecting forms of oppression limit human flourishing, a goal broadly consistent with Catholic social teaching (p. 11). Second, as they correctly note, “Theologians who craft arguments about the human person, God, the Church, and the moral life are people who are themselves embodied, shaped by particular cultural and linguistic traditions, histories, and experiences” (p. 13), and therefore an intersectional approach to theology will aim at analyzing the claims of theologians, or even authoritative ecclesial statements, to critically assess how those statements may have been shaped by their context (pp. 13-14).

In his essay, Choi describes how his experience as an Asian-American scholar and teacher gradually led him to recognize the necessity of adopting an intersectional approach in his work. For example, he looks back on the publication of a volume collecting essays on Asian and Asian American perspectives on Christian ethics that nevertheless followed the structure of traditional Western thinking about ethics and that situated Asian Christian ethical thought into a historical narrative exclusively told in Western terms (p. 63). Likewise, he shares how he increasingly recognized in his experience as a colleague and teacher that, as an Asian American, he was expected to “to be nice, mild, accommodating, agreeable, and accepting of the status quo if [I] want[ed] to ‘pass’ and fit into whiteness” (p. 64). Intersectional analysis can be highly theoretical, but it grows out of concrete experience. For my own part, I, too, have gradually come to recognize the value of this sort of social analysis, through both attentive listening to the experience of people close to me, as well as of students and church members, and critical reflection on my own experience and privilege as a white male. On the other hand, like many, I am sure, I struggle to work out what that means for my own theological work. The following reflections arise from that perspective.

As Clark, Perkins, and Reimer-Barry admit, intersectional approaches to theology have been criticized both inside and outside the theological academy. One of the most common criticisms of intersectional approaches (and related approaches like liberation theology and contextual theology) is that they are reductionist, which can be taken in two senses. First, this form of social analysis seems to reduce human beings to group characteristics such as our race, ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, or social class, when in fact each of us is a complex, unique individual.

At first glance, this accusation seems obviously false. Far from taking a one-dimensional approach to the person, by definition, intersectional analysis is focused on the multi-dimensionality of human experience, particularly the experience of oppression. As Hoon Choi points out in his essay, this actually represents an advantage of an intersectional approach over traditional liberationist or contextual theologies, in which the social analysis tends to be one-dimensional, focusing on social class or culture, respectively (p. 78).

Perhaps a better way to think about this objection is to look at higher education. Critical approaches like intersectional analysis have, in many instances, become a sort of meta-discourse across multiple disciplines, particularly in the humanities. It is now commonplace to analyze works of literature, art, history, philosophy, and religion in terms of whether they reproduce or challenge constructions of race, gender, and sexual identity. Although this approach offers new insights, does it risk dissolving distinct, disciplinary ways of knowing into a homogeneous form of social analysis? From a theological perspective, it may seem unclear if, ultimately, the aim of intersectional theology is discourse about God, or discourse about discourse that is only incidentally about God. Similarly, granted that intersectional analysis can offer a critical assessment of theological discourse, can theological truth claims be used to assess the presuppositions and fruits of intersectional analysis?

The second, related sense in which intersectional analysis is accused of being reductionist is the claim that it reduces social relations to power conflicts. For example, the theologian Charles Camosy writes:

Intersectional critical theory focuses on the interrelated systems of power that cause vulnerable populations to suffer injustice. The bad guys (powerful people and the systems that privilege them) are racist, homophobic, transphobic, ableist, neocolonial, and patriarchal. Each of these sins implies all the others, because the bad guys preside over matrices of domination in which marginal identity categories intersect with and reinforce each other. Against the bad guys, those with marginalized identities—black, LGBT, disabled, immigrant, female—find common cause, though their substantive claims may differ or contradict. For in the matrices of intersectionality, everything boils down to a struggle for power.

Camosy finds this reduction of discourse to a struggle for power particularly damaging for the discipline of theology:

The centrality of power to intersectional discourse . . . makes it highly problematic for Christian academics. Commitment to rational inquiry and argumentation, free speech, and viewpoint diversity are, according to intersectional theory, mere attempts to safeguard privilege. But Roman Catholics, who believe in the salvific nature of Christ’s death and resurrection and the continued work of the Holy Spirit in the world, cannot be at home in a discourse that requires the destruction of the perceived enemies of our identity. We must be faithful to the command of Christ to encounter and engage those with fundamentally different views in a spirit of love—which means, for academic theologians, a spirit of intellectual solidarity.

There is some truth here, since some forms of social analysis (for example, those influenced by Michel Foucault) do reduce social relations to expressions of power. Social analysis along these lines should be problematic for Christian theologians, not just for the ethical reasons described by Camosy, but for ontological reasons, as well. At some level, social analysis must be an attempt to approach the truth of things.

But as Clark, Perkins, and Reimer-Barry point out, intersectional analysis does not depend on such a reductionist approach; rather, at its core, intersectional analysis “analyze[s] the use and abuse of power within complex systems” (p. 4), a task Camosy likewise recognizes as legitimate and helpful. I think rather than making blanket judgments about intersectional analysis one way or the other, it would be beneficial for theologians to take a discerning approach that critically assesses the deep assumptions behind any particular work of social analysis. For example, a group of Catholic ethicists, including myself, are engaged in an ongoing dialogue with the critical realist approach to social analysis, which examines the mutual influence of social structures, cultural patterns, and the agency of human persons. Likewise, Kristin Heyer adopts a critical understanding of social structures and agency that reflects a Catholic understanding of the human person in her essay in the JMT’s special issue (and further develops it in an upcoming book).

On the thorny question of reductionism and the relationship between theology and the social sciences, an important touch point for me has been Pope Paul VI’s 1971 apostolic letter Octogesima Adveniens. A somewhat neglected part of the Catholic social tradition, the letter nevertheless has important insights on democracy, ideologies, and social change.

In a section on “the questioning of the human sciences,” or what we would call the social sciences, Paul VI addresses the problem of reductionism. Although warning of the risk that a reductive approach to the social sciences could “mutilate” the human person, he recognizes that they make a valuable contribution to understanding the person and society (no. 38). In a pregnant phrase, he states, “These sciences are a condition at once indispensable and inadequate for a better discovery of what is human” (no. 40).

Although it is not totally clear what the context for Paul VI’s remarks is, it is likely that he has Marxist social analysis in mind as one type of reductive social science. He addresses Christian attitudes toward Marxism in more detail earlier in the letter (nos. 31-34). He also wrote the letter at a time when a positivist approach to the social sciences, treating them as analogous to the natural sciences, was ascendant, and behaviorism still held significant influence. He also remarks that some have reacted to these developments by calling into question the social sciences. Paul VI may just be referencing Christians who reject the validity of the social sciences, but his language suggests that he may also be referencing postmodern skeptics and critical theorists.

Regardless, his analysis of reductionism is valuable. He warns that just as humankind has gained scientific mastery over nature, “man now finds that he himself is as it were imprisoned within his own rationality; he in turn becomes the object of science.” He points out that the social sciences necessarily “isolate . . . certain aspects of man [sic]” for analysis and study, yet some are tempted to mistakenly draw from this analysis explanations or interpretations of social life that are meant to be “complete” or “all-embracing.” These forms of reductionism “make it impossible to understand man in his totality” (no. 38).

Despite recognizing reductionism as a serious danger, Paul VI presents a positive approach to the social sciences: “Should the Church in its turn contest the proceedings of the human sciences, and condemn their pretensions? As in the case of the natural sciences, the Church has confidence in this research also and urges Christians to play an active part in it.” The key lies in recognizing that “each individual scientific discipline will be able, in its own particular sphere, to grasp only a partial-yet-true aspect of man; the complete picture and the full meaning will escape it” (no. 40).

His scattered remarks on the relationship between theology and doctrine, on the one hand, and the social sciences, on the other, are also provocative. Contrary to some biblical fundamentalists and more sophisticated theological approaches such as Radical Orthodoxy, he does not insist that Christian theology provides the “complete picture,” “man in his totality,” and therefore has no need of social analysis or social theory. Rather, he insists that the Church must engage in dialogue with the social sciences (no. 40). Elsewhere in the letter he suggests that Christianity plays a critical function, challenged reductionist, closed ideologies through its insistence on “concrete transcendence” (no. 29). He also suggests that the Gospel helps Christians make sense of what may otherwise appear to be disjointed aspirations and forms of knowledge: “The death of Christ and his resurrection and the outpouring of the Spirit of the Lord help man to place his freedom, in creativity and gratitude, within the context of the truth of all progress and the only hope which does not deceive” (no. 41).

Paul VI’s remarks on what the Church gains from the social sciences are particularly relevant for the contemporary discussion of intersectional analysis. One fruit of the dialogue between the two will be that the social sciences “widen the horizons of human liberty to a greater extent than the conditioning circumstances perceived enable one to foresee,” which seems to mean that they help us to better recognize structures of oppression, which may remained invisible without critical analysis, and provide us the tools for overcoming them. Perhaps even more intriguing, he says the social sciences can:

. . . assist Christian social morality, which no doubt will see its field restricted when it comes to suggesting certain models of society, while its function of making a critical judgment and taking an overall view will be strengthened by its showing the relative character of the behavior and values presented by such and such a society as definitive and inherent in the very nature of man. (no. 40)

Although this sentence (or at least the translation) is worded awkwardly, it seems to be saying, first, that Christian social morality alone is not sufficient for developing a model of how society ought to be organized, but rather must learn from the social sciences. Second, it suggests that the social sciences can help show that the behavior and values that a society considers given or “natural” are in fact relative, or as we might say, socially constructed, and that these insights will benefit Christian social morality. Although ultimately the Gospel helps us make sense of our world in the way the social sciences alone cannot, the Church also learns from the social sciences, particularly in the field of social morality.

Paul VI likewise takes a dialogical approach to culture and Christian tradition that I think is relevant for contemporary discussions of intersectionality and dialogue. Earlier in the letter, he points out that the Gospel “was proclaimed, written and lived in a different sociocultural context,” but that does not mean it is “out-of-date.” It is “ever new,” and yet also “enriched by the living experience of Christian tradition over the centuries” (no. 4). Although the Gospel is a “universal and eternal message” (no. 4), this does not mean that it somehow floats above culture and social context. Rather, the Gospel is passed on through a form of cross-cultural communication; we encounter the Word that was made flesh in that distant context, but the Word is passed on between cultures, and the Church’s tradition is enriched in the process.

At their best, then, intersectional analysis and related forms of social analysis are methods for analyzing and understanding the profound, multi-dimensional impact that categories like class, race, gender, sexual identity, and so on have on our lives without presuming to give a complete picture of what it means to be human. Precisely because our social experience is multi-dimensional, and because we are individually agents who experience “concrete transcendence” and who both are shaped by and shape the circumstances of our lives, no two people experience their belonging to these social categories in exactly the same way. But that does not diminish the fact that these social categories are in some sense objectively real and shape our shared experience in ways amenable to analysis.

In Paul VI’s terms, intersectional analysis provides us a glimpse of “a partial-yet-true aspect” of our life together that can be of benefit to Christian morality, and even Christian theology more broadly. Therefore, although there is certainly a risk of reductionism in intersectional analysis, as with any type of social analysis, I think with due discernment, intersectional analysis can be a useful tool for theologians. Of course, this is a complex issue and there are other aspects I am leaving unaddressed here.

The most difficult questions regarding intersectionality and theology, in my opinion, center around the notion that the formulations of the faith produced by theologians and church authorities in the past themselves, to some extent, reflect “the relative character of the behavior and values presented by such and such a society,” to quote Paul. How can we incorporate this insight into theological practice while maintaining the truly theological nature of our practice?

I don’t think a one-sided approach to this question—either one that presumes that doctrine somehow floats outside of culture, or one that affords too little of a normative role for theological/doctrinal tradition—will work. Theologizing ought to involve “problematizing Revelation/Tradition in an appropriate way” (Clark, Perkins, and Reimer-Barry, p. 14), but Revelation can’t remain simply a problem, since it is through Revelation that God speaks to us as friends and lives among us (Dei Verbum, no. 2); at the end of the day, theology’s aim ought to be to help us know God, even if our knowing is always limited.

One reason I thought Choi’s contribution to the JMT issue was promising is because he proposes that Revelation itself, for example the doctrines of the sensus fidelium and the Incarnation, provide theological warrants for adopting an intersectional approach. To me, this represents an example of the multi-dimensional approach suggested by Paul VI. I think dialogical approaches such as Choi’s, in which theology and social analysis are mutually enriched and critiqued, is the only solution, but this will necessitate a certain pluralism and experimentation in methods for the foreseeable future, and here I think Camosy is right that this is going to require of us theologians a spirit of charity and intellectual solidarity amidst our differences.

Of Interest…

Continuing a theme from the past few issues of the newsletter, Jenn Morson at America reflects on the killing of Jordan Neely, noting how dehumanizing language, particularly regarding vulnerable people, used on social media and in other contexts can contribute to violence.

A while back I wrote about digital privacy in the context of using data from apps to track priests and their sexual relationships, but Gina Christian has a helpful article about the more everyday problem of cybersecurity at local parishes. Although churches are not very likely to be the victims of ransomware attacks and probably don’t have large databases of private data on file that would tempt hackers, they are still vulnerable to smaller-scale scams and hackers with a personal agenda. The article has some helpful tips on how parishes can improve their cybersecurity and think more carefully about how they use computers and other digital technology.

Although I have not yet written on the issue here at Window Light, many readers may know that over the years I have written quite a bit on the ethics of war and peace in the Christian tradition, and so that is an issue of great concern to me. In the May print issue of Commonweal, Tobias Winright and William Cavanaugh provide opposing views on how to think about the war in Ukraine in terms of Catholic teaching on the ethics of war and peace, an exchange of special interest to me since both Winright and Cavanaugh have had a deep influence on my own theological career, in distinct ways. To put it simply, Winright argues that the war in Ukraine demonstrates the ongoing validity of the just-war tradition as part of how Catholics think about the question of peace, contrary to those who have argued it is obsolete (including, seemingly, Pope Francis). Cavanaugh, on the other hand, insists that from a Christian perspective, there is no “good war”; rather, war is something to be lamented and nonviolently resisted. He also takes a wider lens, critiquing Americans’ selective concern for aggression in Ukraine while failing to intervene in other conflicts, such as that in Syria, and the potential risk of surging Ukrainian nationalism in promoting future conflict and contributing to social strife in a multiethnic Ukraine. I am sympathetic to Cavanaugh’s concerns, having focused for a long time on the factors that contribute to cycles of violence and recognizing that war “is a massive failure by Christians on all sides to imagine the world as Christ would,” but I have to agree with Winright that the just-war tradition remains indispensable for guiding Christians on how to faithfully respond to such failure.

Coming Soon…

During the second half of next week, I will be traveling back to Washington, D.C. for a meeting of the National Council of Churches’ Faith and Order Convening Table. I am a volunteer representative of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops for these ecumenical gatherings. We are close to wrapping up a multi-year project of reflecting together on racism and the Christian churches in the United States, and hopefully I can write up some thoughts when I get back. For next week, however, I should be able to put out a newsletter early in the week, but later in the week I may not be able to do so.

It only now occurred to me that the featured photo on a post on intersectionality is literally an "intersection." I swear that wasn't deliberate, but I kind of like it more that way.

Camosy from his position in 2018 raises valid concerns. I think Archer/Bhaskar is the way to go as in the book you reference, which I decided to order. I think it is a more rigorous approach that just talking about "oppression" or "power". Our agency is mediated in complex ways by the structures in which we function, like it or not. Someone gets to sign our pay checks or not. A good dose of Marx is needed as a cure for too much emphasis on "identities" in my view.