We Have to Do the Works of the One Who Sent Me

Healing and Conversion in the Story of a Man Born Blind

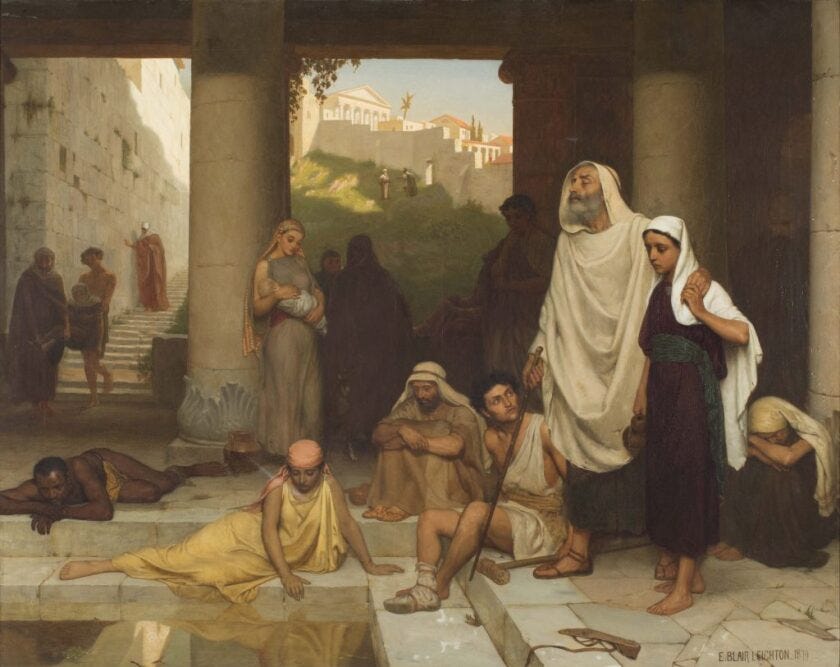

This Sunday’s Gospel reading, which includes the entirety of the ninth chapter of the Gospel of John, is the story of Jesus healing a blind man by placing a mixture of clay and saliva on the man’s eyes. The drama in the story comes from a group of Pharisees who confront the formerly blind man about the healing, questioning whether Jesus, who they considered a sinner, could perform such a sign. By the end, Jesus explains to the man his mission in these cryptic terms:

I came into this world for judgment, so that those who do not see might see, and those who do see might become blind. (v. 39)

Some of the Pharisees overhear Jesus and, catching on that he is referring to them as those those who have “become blind,” they object. Jesus responds:

If you were blind, you would have no sin; but now you are saying, “We see”’ so your sin remains. (v. 41)

Jesus’ message seems to be that those who recognize their need for healing (their “blindness”), either bodily or spiritual (the two are intertwined in this story), come to “see” Jesus as he is, the Son of God and Messiah. Those who do not recognize this need for healing, those who claim to “see,” in reality become blind.

This is one of my favorite stories in the Gospels because of the complexity of the symbolism, the multiple layers of meaning, and the tightness of the narrative structure, but also because it is so directly relatable to the everyday experience of Christians. In this essay I want to explore a couple of themes raised in this story in more detail.

Divine Agency and the Problem of Evil

In this story, the theme of divine agency arises again, this time not only regarding the relationship between God’s actions and human actions, but also the relationship between God’s will and evil. At the beginning of the story, Jesus and his disciples see the blind man, who is identified as blind since birth; later on we also learn that the man is begging.

Jesus’ disciples immediately ask him, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (v. 2) The question presumes that disability or illness is a punishment from sin. Since the man was blind from birth, it is hard to imagine how his blindness could be the result of his own sin. So the disciples must be thinking of passages from the Hebrew Bible such as: “I, the LORD, your God, am a jealous God, inflicting punishment for their ancestors’ wickedness on the children of those who hate me, down to the third and fourth generation” (Ex. 20:5; see also Ex. 34:7, Num. 14:18, and Deut. 5:9). The disciples believe that ultimately God is the cause of the man’s suffering and are simply curious whose human agency was the occasion of the divine wrath.

Jesus, however, re-frames the problem. First, he denies that God inflicted blindness on the man as a punishment: “Neither he nor his parents sinned” (v. 3). Perhaps more interestingly, Jesus teaches his disciples to think of God’s work not in terms of inflicting suffering, but rather as the work of salvation or liberation from suffering: God permitted the man’s blindness “so that the works of God might be made visible through him” (v. 3). He then turns to heal the man.

It also strikes me how different this healing is from a typical “faith healing,” where God heals someone of their affliction as a reward, or perhaps a recognition, of their faith. When my late father was a small boy, he contracted polio (this was a few years before the vaccine became widely available), and he was paralyzed in his legs. His mother took him to a number of faith healers who promised that if he only had faith, God would heal him of his paralysis. Of course, he was never healed, and at least some of the ministers told him this was because of his lack of faith, a terrible thing to tell a six year old. This traumatic experience was an obstacle to my father’s faith for most of his life.

In this Gospel story, however, Jesus acts first. He mixes the clay and saliva and places it on the man’s eyes even before the man has acknowledged Jesus; you might even say it was without his consent! It is only after he is healed that the blind man gradually comes to have faith in Jesus. God does not withhold his healing work until the recipient proves worthy; God offers it generously, and the recipient then cooperates, responding with faith and joy.

The blind man’s growing faith in Jesus is the other aspect of the story I want to emphasize in this essay. In Mark 8, Jesus cures another blind man, again with saliva (8:23). In this case, however, the man only gradually recovers his sight. When Jesus asks the man if he can see, he replies, somewhat humorously: “I see people looking like trees and walking” (v. 24). Jesus repeats his healing gesture, and only then “his sight was restored and he could see everything distinctly” (v. 25). If blindness is a symbol for our need for God’s saving work, the man’s need for multiple tries for the healing to “take” is definitely relatable.

In John 9, however, the man appears to gain his sight all at once. This story emphasizes not the man’s gradual gaining of sight, but his growing faith in Jesus. When the crowd asks the man how he was healed, he responds:

The man called Jesus made clay and anointed my eyes and told me, “Go to Siloam and wash.” So I went there and washed and was able to see. (v. 11)

He gives a factual account of what Jesus had done. When they ask him where Jesus is now, however, he admits that he doesn’t know. He doesn’t know where Jesus is going, or in other words, doesn’t yet understand Jesus’ mission.

The Pharisees then ask the man a similar question, and he gives a similar response. They begin disputing amongst themselves whether Jesus is “from God,” and they ask the man his opinion. This time he responds: “He is a prophet” (v. 17). Now the man acknowledges not just what Jesus had done, but that he is “from God.”

After asking his parents about the blind man’s condition, the Pharisees return to the man and again ask him about Jesus. At this point, the man begins disputing with the Pharisees: “I told you already and you did not listen. Why do you want to hear it again? Do you want to become his disciples, too?” (v. 27). The formerly blind man here indirectly acknowledges that he is now Jesus’ disciple. He has not just objectively identified Jesus as a prophet from God, but has appropriated that belief at a subjective, existential level. He is willing to defend Jesus, and even to suffer for his sake by being thrown out of the synagogue.

Jesus finds the man afterwards and then reveals to him that He is the Son of Man. The man replies:

"I do believe, Lord," and he worshiped him. (v. 38)

In this final stage, after re-encountering Jesus, the man acknowledges Jesus as the Son of Man, and again this is a deeply existential response, leading the man to worship him.

There is a deep symbolism in the formerly blind man’s growing faith in Jesus that has been recognized since the time of the Church Fathers. The man’s journey of faith begins when he washes himself in the Pool of Siloam, which is a symbol for baptism. Earlier I noted that, in this case, Jesus acts first by “anointing” the man’s eyes with clay and saliva, and then asks the man to cooperate in this divine work by bathing in the Pool of Siloam. This closely parallels the Council of Trent’s account of divine and human agency in its Decree on Justification, written many centuries later, which teaches that God offers “prevenient grace” to people “without any merits existing on their part,” but those so called must assent and cooperate with this grace to be justified, leading up to baptism.

The stages in the formerly blind man’s recognition of Jesus represent the process of catechesis as a Christian grows in their faith. In her well-known book Forming Intentional Disciples, Sherry A. Weddell offers a contemporary example of what this catechesis could look like, outlining what she calls five thresholds of conversion that line up very well with the experience of the man born blind (she herself notes this, without developing the point).1

Initial Trust. In this stage, Weddell explains, “A person is able to trust or has a positive association with Jesus Christ, the Church, a Christian believer, or something identifiably Christian.” We might identify this with the blind man’s initial experience of being acknowledged and touched by Jesus, which must have engendered trust, since the man went to wash in the pool as Jesus had asked.

Spiritual Curiosity. At this stage, a person learns about Jesus and desires to know more. After being healed, the man acknowledges to the crowd what Jesus has done, but admits what he doesn’t know, where Jesus has gone. Perhaps this expresses a longing on his part to know where Jesus is going, what his mission is.

Spiritual Openness. At this stage, the person becomes open to the possibility of change as a result of their encounter with Jesus. For the man born blind, this clearly occurs when he acknowledges that Jesus is a prophet. Admitting that Jesus is “from God,” the man recognizes that he has experienced the saving work of God and may be called on to respond in some way.

Spiritual Seeking. This is the stage where a person makes what Weddell calls “a commitment to change,” what I earlier referred to as existential appropriation. The person identifies as a disciple of Christ even as they struggle to discern what that means. In his second confrontation with the Pharisees, the man considers himself a disciple and acts out his commitment by suffering for Jesus’ sake.

Intentional Discipleship. At this point, the disciple builds their life around following Jesus. This is reflected in the man’s recognition of Jesus as the Son of Man and worshiping him.

Just as the man’s washing in the Pool of Siloam symbolically represents baptism, his second encounter with Jesus, where he recognizes him as the Son of Man and worships him, could be said to symbolize the Eucharist, in which we recognize Christ in the sacrament and worship him. Once we have matured in our faith, we join with him in the Eucharist and participate with him in the work of salvation. Intriguingly, at the beginning of story, when Jesus first speaks of God’s works of salvation, he says to his disciples, these are works “we have to do” (v. 4).

One last thought on this story that I can’t fully develop here: The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church defines a “structure of sin” in this way: “the obstacles and conditioning that go well beyond the actions and brief life span of the individual and interfere also in the process of the development of peoples” (no. 119). The story of the man born blind shows that the works of God in history are meant to free us from all of the obstacles that keep us from full human development, whether those obstacles are spiritual, bodily, or structural. In that regard, the theme of blindness in the story is noteworthy, since a kind of blindness towards the way we participate in these structures of sin (such as racism or consumerism) helps perpetuate them (a theme that has been explored, for example, by Kenneth Himes (subscription required)). To be healed, we must come to see how these structures work, including our own role in them, and join ourselves to the saving work of God of overcoming them.

Of Interest…

Thank you to America Magazine for running my essay “Can you be a theologian outside of academia? I’m going to find out,” originally published here on Window Light, on their web site! You can find the original version here, as well.

The Biden Administration was slow to repeal Title 42, a measure restricting most asylum claims at the southern border as a result of COVID-19, and now is on the verge of introducing new policies that mimic those the Trump Administration had put in place before the outbreak of COVID, likewise significantly limiting asylum claims. America has an essay by Bishop Mark Seitz of El Paso calling on the Biden Administration to do better when it comes to welcoming those seeking asylum.

At the National Catholic Reporter, Michael Sean Winters provides his own response to the news that the group Catholic Laity and Clergy for Renewal had spent millions of dollars on location data to track app use by priests, calling it “creepy.” My own analysis is here.

Religious News Service has a fascinating story on the increasing use of robots in Hindu and Buddhist rituals in South and East Asia, including robots that make offerings to the gods and animatronic statues! What would be the Catholic equivalent?

Coming Up…

I am still working on the second half of my reflections on the hermeneutics of Vatican II, or rather, what happened before Vatican II (see here for the first half).

This weekend, I will be attending the Francis at 10 Conference at St. Ambrose University in Davenport, Iowa. I will write about the conference next week.

Sherry A. Weddell, Forming Intentional Disciples: The Path to Knowing and Following Jesus (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 2012), 128-30.