Sunlight in the Window

The Development of a Theological Image

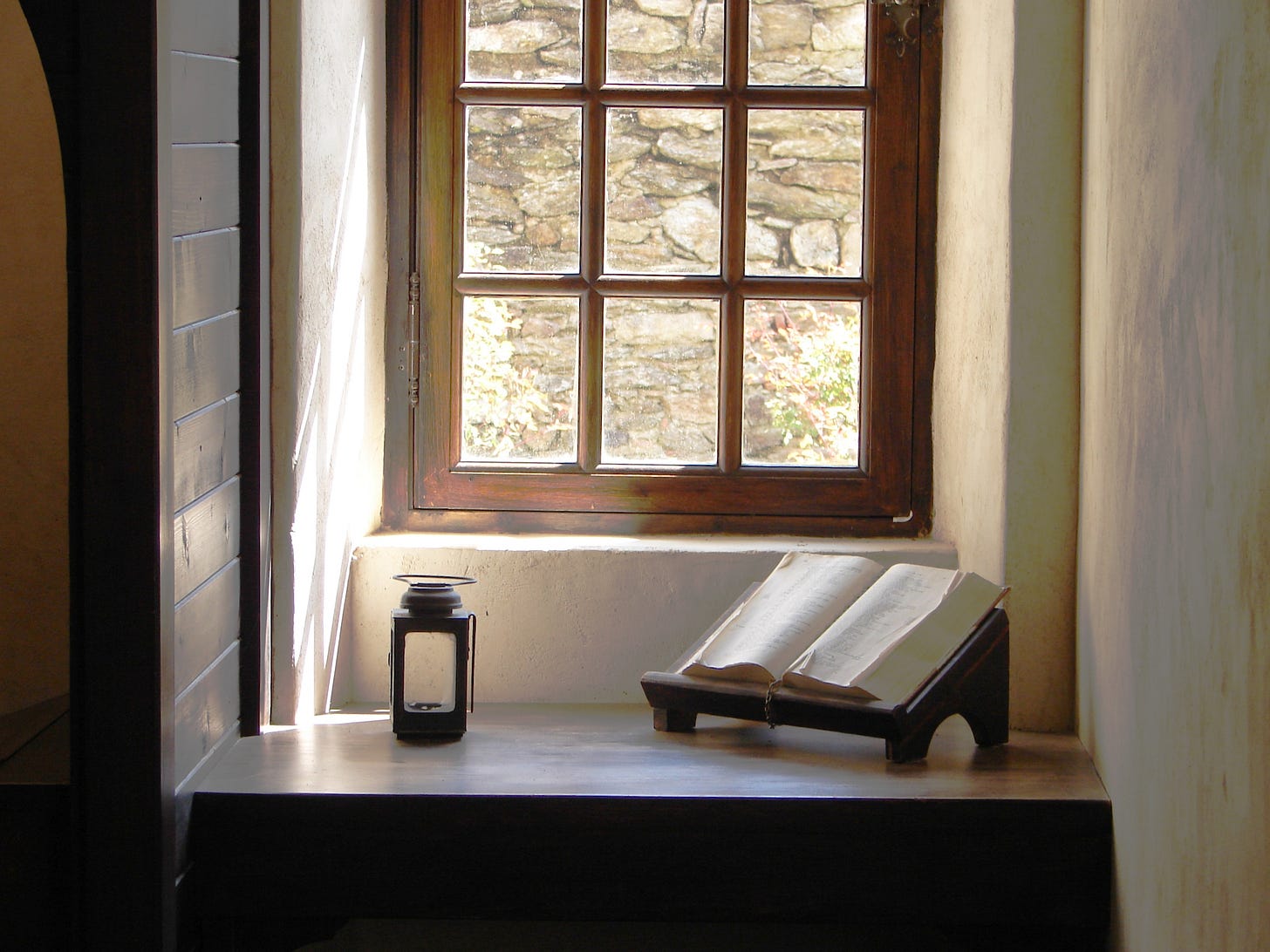

On the About page for this newsletter, I introduce the fourteenth-century Franciscan theologian Peter Auriol’s image of the sun shining through a window, signifying divine grace illuminating the human heart. Auriol’s image is meant to communicate that God’s love is universal. If we experience a lack of grace, it is not because God has abandoned us, but because we’ve created an obstacle to God’s grace, just as closing the window blocks out the sun’s light.

This image was popular in medieval scholastic theology, but its use evolved over time. We often speak about the development of doctrine, but here we have an example of the development of a theological image. In this post I want to trace some of the ways this image of the sun was used and how it evolved.

The ultimate source for the image of the sun is Jesus’ teaching that “[your Heavenly Father] makes the sun rise on the bad and the good, and causes rain to fall on the just and the unjust” (Mt. 5:45, NAB). Jesus here uses the sun and the rain as examples of the universality of God’s love and to show why his followers must love their enemies (Mt. 5:44).

A number of the Church Fathers combined this Gospel image with Platonic symbolism. In his “Allegory of the Cave” from the Republic, Plato had used the sun as a symbol for the divine, the fullness of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. Just as the sun allows us to perceive the truth, goodness, and beauty of earthly things, the divine is the ultimate source of the truth, goodness, and beauty we perceive in the world. Drawing on both these traditions, the second-century Father Clement of Alexandria uses the image of the sun to express God’s omnipresence and omniscience (Clement is also the first theologian I am aware of to introduce a window into the image):

For, just as the sun not only illumines heaven and the whole world, shining over land and sea, but also through windows and small chinks sends his beams into the innermost recesses of houses, so the Word diffused everywhere casts His eye-glance on the minutest circumstances of the actions of life. (The Stromata, Book VII, Ch. 3)

Origen, also in the second century, likewise appeals to sunlight shining through a window to describe our knowledge of God in highly Platonic terms:

Our eyes frequently cannot look upon the nature of the light itself—that is, upon the substance of the sun; but when we behold his splendour or his rays pouring in, perhaps, through windows or some small openings to admit the light, we can reflect how great is the supply and source of the light of the body. So, in like manner the works of Divine Providence and the plan of this whole world are a sort of rays, as it were, of the nature of God, in comparison with His real substance and being. As, therefore, our understanding is unable of itself to behold God Himself as He is, it knows the Father of the world from the beauty of His works and the comeliness of His creatures. (De Principiis, Book I, Ch. 1, no. 6)

These early Church Fathers, then, primarily turn to the image of the sun shining through a window to illustrate the characteristics of God and God’s relationship to creation.

The fifth-century theologian and philosopher Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (so-called because he took the name of Dionysius the Areopagite, a follower of the Apostle Paul) probably provides the most elaborate Christian Platonic use of this image, but also subtly shifts its meaning. He writes:

Now let us consider the name of “Good” which the Sacred Writers apply to the Supra-Divine Godhead in a transcendent manner, calling the Supreme Divine Existence Itself “Goodness” (as it seems to me) in a sense that separates It from the whole creation, and meaning, by this term, to indicate that the Good, under the form of Good-Being, extends Its goodness by the very fact of Its existence unto all things. For as our sun, through no choice or deliberation, but by the very fact of its existence, gives light to all those things which have any inherent power of sharing its illumination, even so the Good (which is above the sun, as the transcendent archetype by the very mode of its existence is above its faded image) sends forth upon all things according to their receptive powers, the rays of Its undivided Goodness. (Divine Names, Ch. 4, no. 1)

Pseudo-Dionysius’s interest here is not just to illustrate the attributes of God, but also, like Origen, to explain how created things share, in a participated way, in those attributes. In a later passage, he describes things that fall short in their participation in divine goodness by suggesting darkness and shadow:

[T]his great, all-bright and ever-shining sun, which is the visible image of the Divine Goodness, faintly reechoing the activity of the Good, illumines all things that can receive its light while retaining the utter simplicity of light, and expands above and below throughout the visible world the beams of its own radiance. And if there is aught that does not share them, this is not due to any weakness or deficiency in its distribution of the light, but is due to the unreceptiveness of those creatures which do not attain sufficient singleness to participate therein. For verily the light passeth over many such substances and enlightens those which are beyond them, and there is no visible thing unto which the light reacheth not in the exceeding greatness of its proper radiance. (Divine Names, Ch. 4, no. 4)

Here Pseudo-Dionysius alludes to Jesus’ teaching that the sun shines on both good and evil, but likewise appeals to Platonic imagery to explain that the darkness of evil does not represent a lack on the part of the sun, that is God, but rather a lack in the creature.

In the Middle Ages, the imagery of the sun shining through a window is put to use to explain more practical theological concepts. The twelfth-century theologian Alan of Lille, who studied and taught at Paris and Chartres, used the image to explain the efficacy of the sacrament of penance. He is here addressing whether God or the confession of the penitent is the cause of forgiveness:

[S]in is forgiven only by the grace of God, and … repentance is not the efficient cause of the forgiveness of sin, only the free will of God is. [Repentance], however, is a sine qua non cause [i.e., a condition for the possibility of something], because unless a person repents, sin is not forgiven by God. Similarly, the sun illuminates the house because the window is opened, yet opening the window is not the efficient cause of the illumination, but only the occasion, but rather the sun is the efficient cause of the illumination. (De Fide Catholica Contra Haereticos, Book I, Ch. 51)

Alan cleverly draws on Pseudo-Dionysius’s use of the sun imagery to explain the absence of goodness in a creature to answer a disputed point in sacramental theology: God is the cause of forgiveness, but forgiveness cannot occur without the repentance of the sinner.

The thirteenth-century Franciscan theologian John of La Rochelle builds on Alan’s imagery, explaining that just as someone must open the windows for the sun’s light to enter a room, we must remove the obstacles to grace in our life to allow God’s grace to transform us. John goes further than Alan by making a more general point about human participation in the work of God. Just as it is the sun that dispels the darkness, even if it in a sense depends on us to open the window, likewise God offers us grace, but we must dispose ourselves to receive it. (John of La Rochelle, Quaestiones de gratia, q. 6).1

The notion of “obstacles to grace” would become central to medieval Franciscan theology. For example, it is an important part of John Duns Scotus’s sacramental theology. As far as I know, however, Scotus does not use the imagery of sunlight shining through a window.

Interestingly, Thomas Aquinas is aware of the image of the sun and the window but rejects it because the sun does not act freely when it leaves a room in darkness because of some obstacle, whereas God, according to Aquinas, chooses to withhold grace when a person creates an obstacle to grace. This may seem like a small disagreement, but in a future post I hope to explain the significance of this difference between Thomist and Franciscan theology.

The fourteenth-century Franciscan Peter Auriol uses the imagery of the sun in a very different context, to describe the predestination of the elect, while using some of the same language as his predecessors. First, Auriol introduces the image of the sun in a familiar way, evoking Matthew 5:45, Pseudo-Dionysius, and Alan of Lille:

A universal agent acts upon everything when there is not an impediment, but if it does not act upon something, that thing has an impediment. Therefore, the sun, for its own part, diffuses the brightness of its rays throughout the air. If, however, a chamber is facing the sun, and yet it is not found radiant on the inside, there must be a positive cause, namely an impediment like a wall or the closing of the windows. If the interior is radiant, there is no cause other than the absence of any impediment, as there is no wall or window interposing between the home and the sun. But it is certain that God is a universal agent from His goodness, willing grace and salvation to every rational creature. For His part, He who makes His sun rise on the good and the evil offers grace to all. (Scriptum super primum Sententiarum)

Auriol goes on, however, to use this image to explain divine predestination:

Therefore, all those who lack grace and salvation do so because of their own impediment and obstacle that God perceives in them. He who has grace and salvation lacks such an impediment. The former is reprobate and the latter is predestined. Therefore, the cause of reprobation is the placing of an impediment foreseen from eternity. The cause of predestination is the foreknowledge and foresight of the absence of any impediment with respect to him who is called predestined. (Scriptum super primum Sententiarum)

In this non-Augustinian account of predestination, God offers grace to all. The “predestined” or “elect” are those God foresees will not create an obstacle to that grace in their lives, while the reprobate are those God foresees will create such an obstacle by sinning and remaining unrepentant.

Through Auriol’s influence, the image of the sun spread outside the Franciscan Order. Later in the fourteenth century, the English Dominican theologian Robert Holcot uses the image in a way similar to Auriol, as does the Augustinian Thomas of Strasbourg. Even in the sixteenth century, the Italian humanist Marcantonio Flaminio wrote regarding predestination:

The Lord’s grace is is like the sun, which by itself illuminates everyone equally, and in this way either not placing or placing an obstacle in front of this supercelestial light is simply the operation of our free will.2

These are the examples of the use of the imagery of sunlight in a window of which I am aware. Share in the comments if you are aware of others, which are certainly out there! Also I want to hear from you if you have any favorite theological images, so share those in the comments.

I became interested in this image of sunlight shining through a window because of the late medieval, non-Augustinian account of predestination associated with it. As I tried to explain on the About page for this newsletter, however, I have come to see it as a powerful image for God’s unfailing love for us and our need to get out of the way of God’s grace (a good modern translation of removing impediments!). My hope is to come back to this image in later posts and explore how it can help us think through some of the spiritual problems we face in contemporary life.

I am relying on Alister McGrath, Iustitia Dei: A History of the Christian Doctrine of Justification, 4th ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020) for my account of John of La Rochelle.

From Marcantonio Flaminio, Lettere, ed. Alessandro Pastore (Rome: Edizioni dell’Ateneo, 1978), cited in Giorgio Caravale, Beyond the Inquisition: Ambrogio Catarino Politi and the Origins of the Counter-Reformation (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2017).