With the election of Pope Leo XIV, much has been made of the fact that he is the first pope from the United States. There are important questions about how his American background has shaped his faith and his leadership style, and in turn about how his pontificate might affect the Catholic Church in the United States. I’ll regularly return to these questions in the months and years ahead, but it’s also important to point out that Robert Prevost spent much of his adult life in Peru, and in fact he was granted Peruvian citizenship in 2015, when he was serving as the bishop of Chiclayo, a city in the far north of Peru.

Prevost’s time in Peru certainly shaped his understanding of the Church and its role in society and therefore is just as important to understand as his American background. And Prevost definitely served the Church in Peru during pivotal historical moments in that nation’s history. For one, he worked for the Augustinian Order there at a time when the Marxist Shining Path movement waged a guerrilla insurgency against the Peruvian state, leading to a violent reprisal from the national police and military, leading to thousands of civilian deaths at the hands of both sides in the conflict. More recently, while he was the bishop of Chiclayo, Peru’s democratic government has undergone an unprecedented constitutional crisis and has been seemingly unable to respond to national crises like the COVID pandemic and a flagging economy. During that time, the Catholic Church has also experienced conflict within its ranks but has increasingly become a voice for human dignity, the environment, and government transparency.

Prevost joined the Augustinians in 1977, made his solemn vows in 1981, and was ordained a priest in 1982. While completing his graduate studies, he was sent as a missionary to Chulucanas, Peru in 1985. The territorial prelature (a local Church not yet rising to the level of a diocese and often considered a missionary area) of Chulucanas was created by Pope Paul VI in 1964 and was led by John (“Juan”) McNabb, an Augustinian friar from Wisconsin, until the year 2000 (Chulucanas became a diocese in 1988, with McNabb as its first bishop). Prevost was assigned to work with McNabb, working in Chulucanas until 1986 when he was reassigned to Chicago to serve as the vocation director for the Augustinian Midwest Province.

After being governed by two military dictatorships since 1968, a democratic constitution was implemented in Peru and elections were held in 1980. Although most groups on the left participated in the election, the Communist Party of Peru, or the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso in Spanish), instead launched an armed insurgency against the new government, starting in the south-central Andean region of Ayacucho, about 250 miles southeast of Lima. At first, Peru’s national police were responsible for responding to the insurgency, but as the violence spread, Peruvian President Fernando Belaúnde handed counterinsurgency efforts over to the military in 1982. Belaúnde declared states of emergency in provinces where the Shining Path was active, suspending civil liberties and giving the armed forces a free hand in responding to the insurgents. The military responded brutally, at times massacring entire communities suspected of sympathies for the Shining Path. The Shining Path were extremely violent, as well, murdering civilian authorities and massacring communities that stood up to them. They have sometimes been compared to the Khmer Rouge of Cambodia in terms of their fanaticism and violence.

In the years after the Second Vatican Council, the leading bishops in Peru were generally progressive. This included Cardinal Juan Landázuri Ricketts, OFM, the longtime archbishop of Lima and president of the Peruvian bishops’ conference, and Luis Bambarén, the bishop of Chimbote who also served as president of the national bishops’ conference. The leadership of these bishops created an ecclesial environment that was hospitable to the emergence of liberation theology, particularly the work of the Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez, who in the 1960s and 1970s served as a pastor in the Rimac district of Lima. In 1984, despite a request from Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, then the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the Peruvian bishops refused to condemn Gutiérrez’s theological work (as described in this 1985 Commonweal article by Christine Gudorf).

By the 1980s, the theology of Gutiérrez and other liberation theologians had begun to influence pastoral practice in the poor neighborhoods of Lima and in parts of the Andean highlands, in many cases in areas pastored by foreign missionaries like the Augustinians or the Jesuits. The Shining Path, however, opposed any efforts to organize the poor outside their leadership and over the years killed a number of priests and religious brothers and sisters, as well as trade unionists and community organizers. Perhaps the most well-known among the latter was María Elena Moyano, an Afro-Peruvian community organizer in the Lima neighborhood of Villa El Salvador, who was killed by the Shining Path in 1992.

Throughout Latin America, liberation theologians in the 1970s wrestled with the question of whether Christians could participate in revolutionary violence against oppressive governments. The Peruvian Church’s encounter with the Shining Path in the 1980s, however, turned most leftist Catholics in Peru away from the revolutionary option, instead encouraging a focus on community organizing and fostering authentic democracy that remains relevant to the present day.

The Shining Path were less active in the north of Peru, where Prevost was stationed, but even here he experienced their violence. The door of the church where Prevost served was destroyed by a bomb set off by the group, according to a priest of the Chulucanas diocese who was a seminarian at the time, and the guerrillas threatened to kill Prevost and the other North American priests serving in the mission if they did not leave the community within 24 hours, a threat the priests ignored. The Augustinians, including Prevost, adopted a pastoral style of closeness to the people who were struggling with poverty and the threat of violence.

After a brief stint in Chicago, Prevost returned to Peru in 1988 where he served as the Augustinians’ formation director in the northern city of Trujillo until 1998, also serving as the prior of the community there from 1988 to 1992. During that time, the Shining Path insurgency continued to intensify, spreading to the outskirts of Lima. In 1990, the relatively unknown candidate Alberto Fujimori won the Peruvian presidential election, replacing Alan García, who had failed to halt the insurgency and whose policies had sent the economy into a crisis.

Breaking his campaign promises, Fujimori began implementing “shock therapy” economic policies of deregulation and privatization (known as the “Fujishock”) that, over the course of the 1990s, led to steady economic growth and a decrease in the poverty rate. Facing roadblocks to his economic policies and efforts to halt the Shining Path in the opposition-led legislature, however, in 1992 Fujimori, with the connivance of the armed forces, undertook a “self-coup,” suspending the constitution and dissolving the legislature and the courts. Fujimori essentially ruled as a dictator until 1995, when elections were held under a new constitution created in 1993. Despite international condemnation, Fujimori’s coup was popular in Peru (although the media was restricted at the time). Fujimori was elected to a second term in 1995, his popularity resting on the perceived success of his economic policies and the near defeat of the Shining Path. The group’s head, Abimael Guzmán, and several other leaders were captured in 1992, mere months after Fujimori’s coup, leading to the significant weakening of the Shining Path. The combination of democratic and authoritarian characteristics under Fujimori’s rule foreshadowed later governments like that of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and Recep Erdoğan in Türkiye.

Although the military still played a counterinsurgency role in combatting the Shining Path, Fujimori increasingly relied on the country’s intelligence services, which relied on intrusive surveillance techniques and the use of violent death squads, most notoriously the Grupo Colina. The latter carried out the murders of several students, journalists, and others allegedly sympathetic to the Shining Path throughout 1991 and 1992. In general, the intelligence services used extrajudicial detentions, torture, and murder against the Shining Path and regime opponents alike. Also, from 1996 to 2000, Fujimori’s government undertook a forced sterilization campaign among indigenous women in the Andes, eventually sterilizing over 200,000 women without their consent.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Pope John Paul II appointed a number of more conservative bishops in Peru, balancing the more progressive tendencies represented by Landázuri and Bambarén. Many of these bishops were affiliated with the group Opus Dei, founded in Spain in the 1930s; at one point, twelve of Peru’s bishops were members of Opus Dei. Certainly, the most well-known of these was Juan Luis Cipriani, who, coincidentally was appointed the auxiliary bishop of Ayacucho in 1988 and the archbishop of the city in 1995. Cipriani, therefore, led the Church in the region at the heart of the Shining Path insurgency. Cipriani went on to serve as the archbishop of Lima from 1999 to 2019 and was appointed a cardinal by John Paul in 2001.

The Sodalitium Christianae Vitae was another conservative Catholic movement founded in Lima in 1971 which grew through in the following years, ironically with the initial support of Cardinal Landázuri. The Sodalitium was approved as a Society of Apostolic Life of Pontifical Right by Pope John Paul II in 1997. More recently, Pope Francis dissolved the Sodalitium earlier this year, one of his last acts as pope, after years of investigation and the dismissal of the group’s founder, Luis Fernando Figari, and several of its leaders over cases of physical abuse, spiritual abuse, and other abuses of power.

In Peru, both Opus Dei and the Sodalitium Christianae Vitae have been associated with the more traditionalist wing of the Catholic Church and with right-wing politics. For example, during his time in Ayacucho, Cipriani refused to cooperate with groups investigating human rights abuses committed by the military, and in 1995 he supported an amnesty for military officials who committed crimes during the insurgency. This right-wing politics was generally tied to fierce anti-communism (and opposition to liberation theology within the Church).

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, other Catholic groups partnered with human rights organizations to investigate human rights abuses by both the Shining Path and the government and to make these abuses known. The Episcopal Commission for Social Action (CEAS in Spanish), an office of the Peruvian bishops’ conference, became particularly important, coordinating these efforts and promoting the Church’s social doctrine in the midst of the conflict. The work of these and other groups laid the groundwork for that of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (which included several representatives of the Catholic Church among its members) established in 2001, after Fujimori’s downfall, which produced a definitive report on the human rights abuses that occurred during the conflict. During this time, the Church took on the role of a witness to truth and the dignity of the person in the midst of propaganda, misinformation, and obfuscation.

In Trujillo, Prevost was relatively isolated from the violence of the Fujimori era, we do know from later events what he thought about those times. When then President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski pardoned Fujimori in 2017, Prevost, by then serving as the bishop of Chiclayo, condemned the decision and even stated that Fujimori should apologize to the Peruvian people for the crimes committed under his rule. Prevost, however, was almost certainly aware of the work of CEAS and other groups during the 1980s and 1990s and was impacted by the Church’s role as a witness to truth.

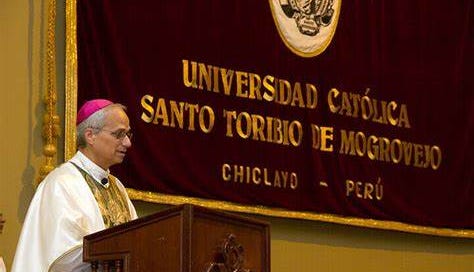

In 1999, Prevost returned to the United States, and two years later he moved to Rome to serve as the prior general of the Augustinians. When Pope Francis appointed Prevost as the bishop of Chiclayo in 2014, the diocese had been led by Opus Dei-affiliated bishops since 1968 (Ignacio Orbegozo from 1968 to 1998, and Jesús Moliné from 1998 to 2014). Prevost’s arrival represented a significant change in pastoral approach, but, according to Kevin Flaherty, SJ, who knew Prevost while he was in Peru, “I think he won over the hearts of so many people in the Diocese of Chiclayo because he’s a man who, like Francis, would be out there, going to visit the rural communities, walking with the people, at the same time, trying to unify the diocese.”

According to Ximena Valdivia Muro, the current head of youth pastoral ministry in Chiclayo, Prevost was open to Catholics of whatever persuasion, be they traditionalists, advocates for liberation theology, or those affiliated with the Charismatic Catholic Renewal, a movement that has spread throughout Latin America since the 1980s. He therefore demonstrated a synodal style of listening and the capacity for unifying Catholics of divergent perspectives that helped get him elected pope.

During his time in Chiclayo, however, Prevost not only had to manage the differences within the Church but also respond to Peru’s ongoing political crisis. This crisis is multilayered. For one, the country still wrestles with Fujimori’s legacy. His daughter Keiko has run for the presidency in 2011, 2016, and 2021, appealing to those who remembered her father fondly or who feared the policy of more left-wing candidates, often falsely accused of having sympathy for the Shining Path. Fujimori himself was pardoned in 2017, although the pardon was repeatedly revoked and reinstated until he was eventually freed from prison in 2023, only to die the following year.

Second, Peru faces the serious problem of corruption. Each of Peru’s elected presidents since Fujimori’s downfall in 2001 has been charged with corruption of various kinds. Alan García, who was reelected in 2006, killed himself in 2019 to avoid being arrested as part of a massive corruption investigation. But corruption is also pervasive in Peru’s Congress, where legislators are protected by immunity. The Congress, whose majority in recent years has been composed of members of the Fujimorist Popular Force party and other right-wing parties, has resisted attempts at reform or even a constitutional overhaul, a major source of the ongoing political crisis.

In 2019, then President Martín Vizcarra, who had assumed the presidency after Pedro Pablo Kuczynski had resigned in the midst of a corruption scandal, dissolved the Congress (a move permitted by the constitution although in this case undertaken under ambiguous circumstances) after it had resisted his efforts combat corruption. And in 2022, the left-wing president Pedro Castillo was impeached after he attempted a self-coup in response to the conservative-dominated Congress’s ongoing obstruction of his agenda and repeated attempts to remove him from office through politicized impeachment proceedings. The current president, Dina Boluarte, took the reins after Castillo’s impeachment, but completely alienated the public after the massacre of at least 28 people in response to protests against Castillo’s removal from office. Boluarte is perhaps the least popular democratic leader in the world, with her approval rating regularly below five percent.

This ongoing institutional crisis has kept the Peruvian government from responding to the challenges of the past few years. The government’s response to the COVID pandemic, for example, was ineffective, leading to months of lockdown and a slow rollout of access to vaccines. Peru’s economy was also dramatically impacted by COVID, leading to a 30 percent drop in gross domestic product, and the nation’s political leaders have struggled to revive the economy. The squabbles of Peru’s political leaders seem disconnected from the struggles of everyday Peruvians.

In Chiclayo, Prevost responded to the community’s needs even when the government was slow to act. That was certainly the case during the worst period of the COVID pandemic, when Bishop Prevost helped organize the distribution of oxygen to households where it was needed to assist those who were sick. Prevost also advocated for migrants from Venezuela who had started coming to Peru in large numbers in 2017 after the former country’s economic collapse, creating a political and humanitarian crisis for Peruvian leaders. As a bishop, Prevost represented a new style of pastoral leadership also represented by other Francis appointees like Carlos Castillo Mattasoglio, the archbishop of Lima who succeeded Cipriani (appointed a cardinal in 2024) and Pedro Barreto, the archbishop of Huancayo (appointed a bishop by John Paul II, but named a cardinal by Francis in 2018). These bishops seek to accompany the poor, stand up for human dignity and the environment (an important issue in Peru, which faces challenges protecting the Amazonian rain forest and sustainably managing its mineral resources), and advocate against corruption in politics, while promoting a missionary spirit in the Church.

These bishops represent a vision of the Church that offers a prophetic witness in Peru against corruption, narrow populism, and a lack of solidarity. Such a vision would resonate in the United States and other parts of the world, as well. Hopefully Pope Leo XIV can draw on his pastoral experience in Peru, gained in a complex political and ecclesial context, in order to share this vision with the world.

Of Interest…

Few know Chicago Catholicism as well as Margaret O’Brien Steinfels, the former editor of Commonweal. Writing for that magazine, she offers some reflections on how Chicago Catholicism might have shaped Pope Leo XIV: “If Pope Leo seems to many like a man comfortable in his own skin, it may be partly because he grew up in a Church comfortable in its city.”

Kilmar Abrego Garcia is a Salvadoran immigrant who was deported to El Salvador based on what the Trump administration admitted was “an administrative error” and held, with an indefinite term of incarceration, in that country’s Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT), an imposing maximum-security prison that has been repeatedly criticized by human rights organization for the mistreatment of inmates. Although the Trump administration had claimed for weeks it could not facilitate Abrego’s return to the US, this past week he was returned, although immediately indicted on questionable charges of human smuggling. Although Abrego’s case has generated the most public interest, it is important not to forget that there are also over 200 Venezuelan migrants still confined at CECOT, deported without due process. At the end of May, the bishops of El Salvador issued a pastoral letter condemning the confinement of migrants from the US in CECOT, describing it as a violation of human rights. The letter takes a wider view, as well, criticizing the abuses in the prison and the recent arrest of a human rights advocate investigating these abuses. The bishops of El Salvador are very much carrying on the tradition of CEAS in Peru and Archbishop Óscar Romero in their own country. Hopefully this message from their fellow bishops in El Salvador can inspire the US Catholic bishops to speak out more clearly on matters in the United States.

This is the most insightful piece I have read about Pope Leo's time in Peru. Thank you for all your work. My only recommendation, if you are interested, is that it was hard to follow the timeline of things in the piece. I don't know if the best framing is pre-Prevost, during Prevost, post-Prevost--but I feel like the narrative was hard to follow. Nonetheless, this is such an excellent piece!