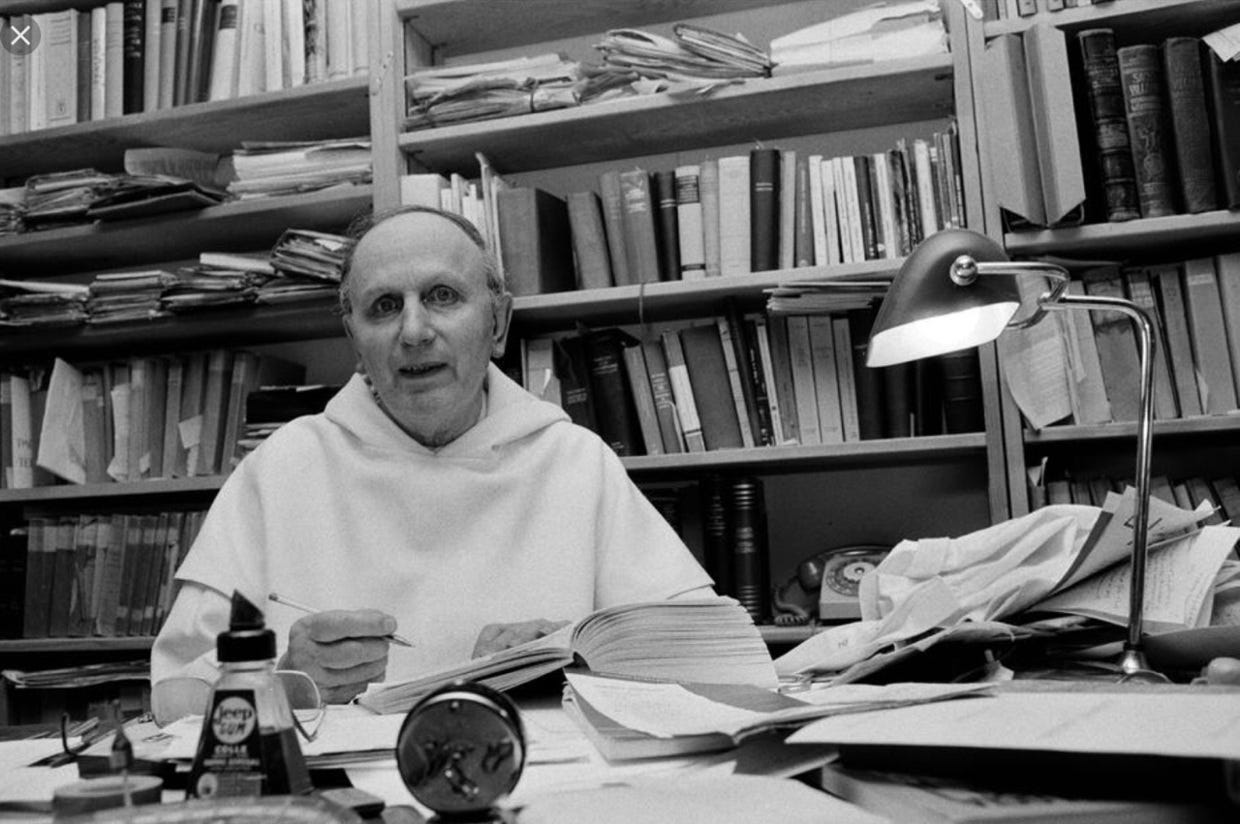

At America, James T. Keane has an insightful article on the theologian Yves Congar, O.P. and his role at the Second Vatican Council. Citing the theologian Avery Dulles, S.J. and the church historian John W. O’Malley, S.J., Keane proposes that Congar could be considered the most important theologian at the council and, taking into consideration his influence on the Church’s teaching, perhaps the most influential Catholic theologian of the 20th century. America has also republished a 1967 interview with Congar, conducted by the noted American ecclesiologist Patrick Granfield, O.S.B. The interview provides insights into Congar’s thinking and also includes some entertaining nuggets, a few of which I will include below.

Earlier this week, I wrote about how Pope Francis’s recent apostolic letter Ad Theologiam Promovendam, in which Francis embraces a “paradigm shift” in theology, could be read in light of the legacy of the early 20th century nouvelle théologie movement that had a decisive impact on Vatican II, and the movement’s eventual split into opposing camps after the council. I resisted, however, Larry Chapp’s effort to tag Pope Francis as siding with the more progressive Concilium group, particularly Karl Rahner, S.J., in opposition to the Communio school of Henri de Lubac, S.J., Hans Urs von Balthasar, and also Francis’s predecessors Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

Despite his central importance to 20th-century theology, Congar’s name didn’t come up in my essay, except for a brief mention in a quotation from the theologian Thomas Weinandy, O.F.M.Cap., another of Pope Francis’s critics. In part, that’s because Congar doesn’t fit neatly into post-conciliar theological dichotomies. Of course, Congar was a founding member of the board of the journal Concilium (as were de Lubac, Balthasar, and Ratzinger) and remained affiliated with Concilium after de Lubac, Balthasar, and Ratzinger broke away to found the rival journal Communio in 1972. Like his teacher Marie-Dominique Chenu, O.P., Congar put a relatively progressive, historical interpretation of St. Thomas Aquinas at the center of his theology:

For me, St. Thomas is a master of thought, and he can form the mind and the judgment. In all his writings he showed he had a great respect for the truth. He was a model of loyalty and intellectual honesty and looked for the truth wherever he could find it. He was not one merely to repeal conclusions that he formed once and for all. All his life he searched for new texts, and for new translations from the Greek or the Arabic. As a man of dialogue, he frequently entered into discussion with the “heretics” of his day. St. Thomas is the symbol of open-mindedness, the genius of reality. We should remain faithful to his spirit.

Indeed, many of the major figures associated with Concilium, including not just Chenu and Congar, but also Rahner and Edward Schillebeeckx, O.P., continued to work within an essentially Thomist framework (de Lubac, in fact, believed that the progressive theologians had unwittingly inherited some of the flaws of the earlier neo-scholastics).

On the other hand, like de Lubac and Balthasar, and unlike Chenu, for example, Congar was steeped in the work of the Church Fathers, even if he continued to view Aquinas as a culmination of earlier theology. Unlike Rahner and Schillebeeckx, there was no philosophical system undergirding his theology, as he himself notes in the interview with Granfield:

I was brought up with a kind of contempt for all moderns. Everyone who had written after St. Thomas was rejected. Men like Blondel, Laberthonnière and Maréchal were considered as contributing nothing to philosophy. I have read nothing of Maréchal. Blondel and Laberthonnière have always interested me because of the contribution they have made to theology. I am convinced that in time Blondel’s importance will grow even greater. When I realized that these men had great minds and had much to say, I began reading them earnestly. But by that time it was too late. I can say that I had no real philosophical formation.

And later:

Fr. Rahner has a philosophical basis that I do not possess. His approach to theological and pastoral problems shows this quite clearly. He generally proceeds from concepts that he examines thoroughly and then specifies. Or he might examine the conditions that, a priori, render a problem accessible and soluble. Thus he is able to take a new look at a problem and hit upon an essential aspect of it in a new way.

Congar’s post-conciliar work was focused primarily on completing his trilogy I Believe in the Holy Spirit, and largely avoided the polemical issues that divided the two schools. And Congar was made a cardinal by Pope John Paul II in 1994, the year of his death, suggesting a certain acceptability in more conservative circles.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Window Light to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.