"Worker Theologian" as a Distinctive Vocation?

Some Thoughts on Being a Theologian in a Non-Theological Job

This past Monday, the Catholic Theological Society of America (CTSA) hosted a virtual event, “The End of the Golden Era: Theology in the Age of Academic Precarity,” in which I participated as a panelist, along with Mary Beth Yount, Catherine Punsalan-Manlimos, and Kate Ward. Mary Kate Holman (whom I interviewed for the newsletter back in April on her work on the French theologian Marie-Dominique Chenu, O.P.) acted as the moderator. The focus on the event was the precarious state of theology at Catholic universities in the face of budgetary challenges and a society-wide decline of interest in the humanities, including theology.

For my part, I talked about my experience of trying to live out the vocation of a theologian without being a professor of theology, and the challenge of maintaining that vocation when doing some other kind of work, a topic readers know I have discussed before in the newsletter (here, here, and here). Citing the Czech theologian Tomáš Halík’s argument that the Church today must learn to recognize “the branches that are alive and those that are dry and dead,” I suggested that the field of theology is undergoing a similar process of dying as new forms of life are born, and that many theologians will likewise experience a kind of dying to self, a potentially painful letting go of the future in academia we expected, even as we discern new ways of living out our vocation.

After the panel, participants at the event joined the panelists in breakout rooms to further discuss the themes raised in the panelists’ remarks. In my room, we discussed what kinds of institutions might provide theological education or opportunities for theologians to engage in scholarly work outside of higher education, and also how someone might live out the vocation of a theologian while working as something other than a professor. A number of peopled shared their own stories of working outside of academia, highlighting some of the different shapes this might take, which I found encouraging. One participant proposed that we ought to think of this sort of vocation as something like the “worker priests” of the 1940s and 1950s—“worker theologians,” if you will. I found this suggestion intriguing, not least because the worker priest movement embodied a provocative way of envisioning the relationship between the Church and the world that I’ve written about (and also see my interview with Mary Kate Holman, mentioned above). I think re-thinking the vocation of the theologian will require creative new ways of living out our faith in the world. I wanted to share some initial thoughts on the idea of “worker theologians” here and potentially get feedback from readers.

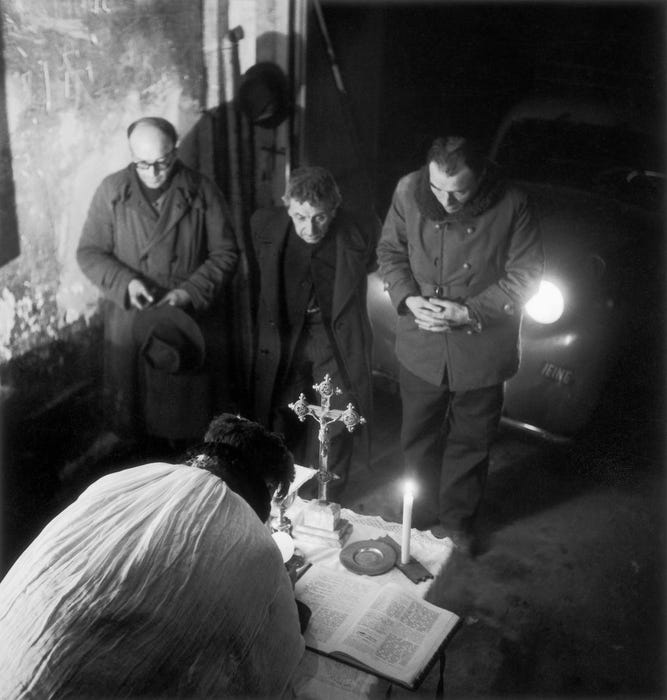

Before considering the idea of a “worker theologian,” however, I want to quickly summarize what the worker priest movement was all about. During the Second World War, the experiences of French priests sentenced to labor camps by the Nazis or working as part of the Resistance developed their sense of solidarity with the working class but also brought home how alienated the French working class had become from the Catholic Church. In 1944, to respond to this challenge, the first worker priest missions were established in Paris, and later in other cities. The worker priests were excused from their normal obligations as priests and eschewed clerical dress, instead working alongside workers in factories, adopting the latter’s way of life.

The mission of the worker priests was not to directly evangelize the workers by preaching, catechizing, or performing the sacraments. Rather, the purpose was to learn about the lives of the working class, to make working-class culture less foreign to the Church, and to “accompany” the workers in their struggles, to use a more recent term. This was a more subtle form of evangelization, carried out by building trust and expressing solidarity. Over time, however, many of the worker priests became involved in union activity, including participation in the Communist labor union, and some were involved in labor unrest. These developments led to the suppression of the movement by Pope Pius XII in 1954.

With that background, I think it’s clear there are some important differences between the worker priests and a “worker theologian” in the contemporary context. For one, the worker priest mission was deliberately established to bring the Church to the workers, and to help the Church be more at home in working-class culture. In contrast, there is no organized effort to bring theology to the world of work or anything like that. People identify a vocation as a theologian working outside of academia either as a professional choice (for example, if they are simply not interested in working in academia) or, as with me, as a response to the precarious situation in higher education and personal circumstances. That doesn’t mean, however, that theologians working outside of academia couldn’t be intentional about articulating a shared sense of purpose or identity as a distinct theological vocation.

Second, the vocation of a “worker theologian” is not focused on a particular social class the way the worker priest mission was. Indeed, perhaps the term “worker theologian” is misleading if the word “worker” connotes the working class. I would imagine most people who identify as theologians but who are working outside of academia would nevertheless be engaged in “white collar” or professional work. For example, one of the participants in my breakout room mentioned that she worked as a psychologist. That doesn’t mean that there couldn’t be working-class theologians, though.

Despite these significant differences, however, I think drawing on the experience of the worker priests as a source for understanding the vocation of a theologian working outside of academia can still be valuable for the following reasons. First, just as one of the purposes of the worker priest mission was to learn about the world of the working-class and in a sense transform the Church with that knowledge and experience, the experience of working outside of an academic or Church setting can enrich the work of theologians and bring new insights to the field of theology. A changed context for doing theology will impact the form that theology takes. Historically, theology done in pastoral, monastic, and university settings has addressed different types of questions and been expressed in distinct genres, and so theology produced in the context of more secular work will likely be distinctive, as well.

This was a helpful insight for me because my initial way of thinking about my situation was to see my employment and my theological work as separate. My job would be a way for me to usefully use my gifts and talents and make money to pay the bills, and my theological vocation would be something I live out on my own time, with the two having little to do with each other. And I suppose there is some truth in that. But theologian or not, my vocation as a lay person is to live out my faith through my work and through family life, and if theology is critical reflection on faith (“faith seeking understanding”), then the experience of working outside a classroom will inform my theology, and as more people share that experience, it will inform the entire field of theology, and potentially the Church.

Another insight I gained from Monday’s conversation is that even when your professional work is not theologically oriented (i.e., a theology professor or pastoral minister), theology can nevertheless inform your work. For example, the psychologist I mentioned earlier explained that her theological studies have impacted her work counseling others. I think in other areas, this integration will necessarily be more subtle. For example, in my new position, I will be focusing on the assessment of student learning at a public university, and so I don’t anticipate that my theological research will inform that work in any direct way (although who knows?). But I can still imagine ways that my theological interests might be integrated with my professional work as part of my own personal development.

These are just some sketches of thoughts based on the great conversation at the CTSA event last Monday. Obviously, my thinking on this topic is a work in progress. If you have any reflections, counterpoints, or examples, please share them in the comments, or if you know of anyone who has written more substantially on this distinctive vocation, please share!

Thanks for your summary of the CTSA mtg and your thoughts about "worker theologians," Matt. I had a competing commitment, so I missed the session and appreciate your summary. I also find your idea of "worker theologians' quite provocative and exciting (a much better term than "independent contractors" or "independent scholars" (though I realize those terms might "count" with the IRS (whether that's good or bad, I don't know....). I hope this conversation will continue tire(also for those who step out of academic to "retire" but are not uninterested in continuing to have a theological voice/community.