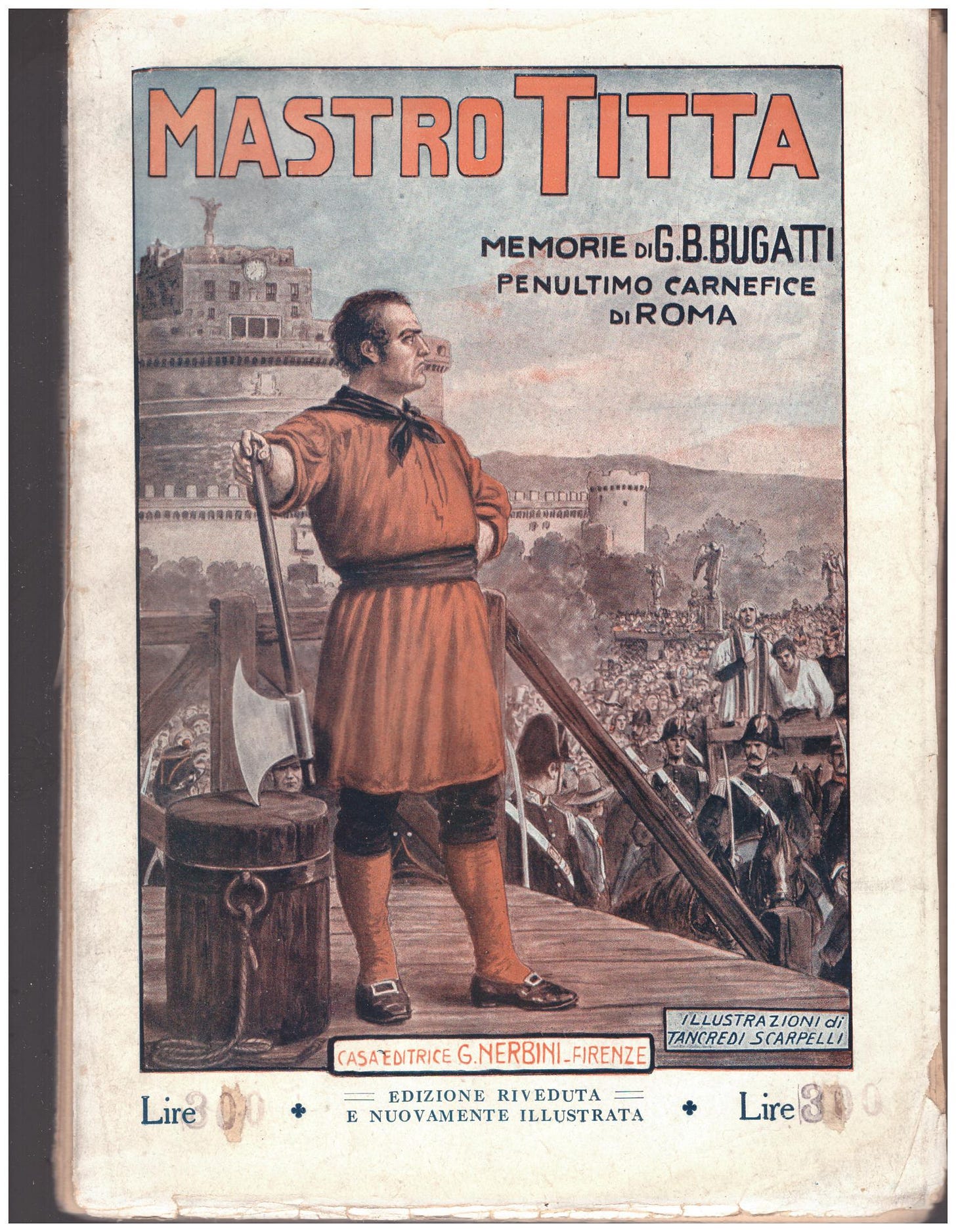

Giovanni Battista Bugatti was the official executioner for the Papal States from 1796 until his retirement in 1864, serving under six popes and executing 516 criminals. Bugatti (popularly known as “Mastro Titta,” derived from maestro di giustizia, “master of justice”) was a minor celebrity; crowds would gather whenever they saw Bugatti crossing the Castel Sant’Angelo bridge to the piazza at its southern end where executions were often held. The most common tool of Bugatti’s trade was the guillotine, ironically developed during the French Revolution as an instrument for the overthrow of both throne and altar, but which passed into Roman usage during the intermittent periods of French rule over the Papal States between 1798 and 1814.

Although he was certainly the most famous, Bugatti was not the last papal executioner—his successor continued his grisly work until the fall of the Papal States in 1870. Even though capital punishment was banned in Italy beginning in 1889 (although it was temporarily revived during the fascist era and the years immediately after World War II, 1926-1947), the Vatican permitted capital punishment, although only for the crime of attempting to assassinate the pope, from the time of the passage of the Lateran Treaty creating the Vatican City State in 1929 until the law’s abrogation in 1969 by Pope Paul VI, a quite different Giovanni Battista (obviously this law was never put into practice).

In 2018, Pope Francis updated the Church’s Catechism to read that the death penalty is “inadmissible,” in part because “there is an increasing awareness that the dignity of the person is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes” (2267). Finally, earlier this year, the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) released the declaration Dignitas Infinita (DI), a defense of human dignity. It states that it “also violates the inalienable dignity of every person, regardless of the circumstances” (34).

In addition to the death penalty, the final section of DI lists several other conditions or practices that official Catholic teaching considers violations of human dignity, including: extreme poverty; war; the mistreatment of migrants and refugees; human trafficking and slavery; sexual abuse; violence against women, and the inequality of women more generally; abortion; surrogacy; euthanasia and assisted suicide; the spread of “gender theory,” or “attempts to obscure reference to the ineliminable sexual difference between man and woman” (59); sex-change procedures; and cyberbullying and other forms of “digital violence.” As I noted in an earlier commentary on DI, the declaration suggests that the notion of “dignity” can unify Catholics who may identify more closely with some of these issues rather than others and who may stand on opposite sides of the political divide.

In a more recent article, I also explained how DI traces how the Catholic Church’s understanding of human dignity has developed over the centuries, noting important antecedents of the modern teaching such as the biblical testimony that we are created in the image and likeness of God and the emergence of the understanding of a person as a “subsistent individual of a rational nature.” By acknowledging the roots of the Church’s modern teaching on dignity in the Tradition, the declaration is a powerful polemic against traditionalists who have challenged the Church’s applications of the notion of dignity to issues like religious freedom.

The story of Giovanni Battista Bugatti, however, is missing from DI’s historical narrative. Of course, I wouldn’t expect a doctrinal declaration to talk about a somewhat obscure historical figure like Bugatti, but a document attempting to trace how the Catholic Church’s understanding of human dignity has developed over time should acknowledge the ways that the Church has historically been complicit in some of the very practices DI identifies as violations of human dignity, a complicitly vividly highlighted by Bugatti’s career. Other examples would include the Church’s centuries-long toleration for slavery and institutional involvement in slave ownership, the promotion of misogyny in doctrine, theology, and cultural practice, and the contemporary sexual abuse crisis in the Church, among others.

Likewise, an adequate account of doctrinal development regarding human dignity should acknowledge how theologians, including those like St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas who are cited in DI as contributing to the development of the Church’s understanding of dignity, offered defenses of these violations in the name of Catholic truth. These historical facts should be included for intellectual reasons—for example, to answer the question how the Church and its theologians got these issues wrong—but more importantly for moral reasons, as a form of repentance for the Church’s failures to fully recognize the human dignity it now proclaims to the world.

The exclusion of this darker side of the development of the Church’s teaching on dignity from DI is somewhat unexpected, particularly in light of the Church’s increasing recognition of the need to repent of past sins committed in its name, beginning especially with the pontificate of Pope John Paul II. Maddeningly, recent statements by the Vatican on some of the issues listed in DI do in fact include references to the Church’s past complicity in these violations of human dignity. For example, in the address in which he announced his intention to amend the Catechism’s teaching on the death penalty, Pope Francis was highly critical of the Church’s past teaching and practice:

In past centuries, when means of defense were scarce and society had yet to develop and mature as it has, recourse to the death penalty appeared to be the logical consequence of the correct application of justice. Sadly, even in the Papal States recourse was had to this extreme and inhumane remedy that ignored the primacy of mercy over justice. Let us take responsibility for the past and recognize that the imposition of the death penalty was dictated by a mentality more legalistic than Christian. Concern for preserving power and material wealth led to an over-estimation of the value of the law and prevented a deeper understanding of the Gospel. Nowadays, however, were we to remain neutral before the new demands of upholding personal dignity, we would be even more guilty.

Similarly, at the press conference announcing the release of DI, Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández, the Prefect of the DDF, made reference to the Church’s prior support for slavery. As Cindy Wooden reported:

“Human dignity is a central question in Christian thought,” Cardinal Fernández told reporters. “It has had a magnificent development over the past two centuries along with the (development) of the social doctrine of the church.”

The cardinal used the example of slavery, which was accepted in the Bible and by popes for centuries. In 1452, Pope Nicholas V allowed King Alfonso V of Portugal the right to enslave certain people, he noted. Then, in 1537 Pope Paul III “condemned with excommunication those who subjected others to slavery. Why? Because they are human. That was the only reason. Because they are human.”

Of course, the history of the Catholic Church’s involvement with the institution of slavery is more complex than Cardinal Fernández let on, as found in Christopher J. Kellerman, S.J.’s recent book All Oppression Shall Cease: A History of Slavery, Abolitionism, and the Catholic Church, for example, but at least here Fernández admits the Church’s past complicity and that there has been significant development in the Church’s doctrine. The fact, then, that DI itself does not even acknowledge these reversals in the Church’s teaching or the Church’s historical complicity in these and other practices is all the more remarkable.

Respect for human dignity should entail telling the truth about historical violations of dignity and the victims of those practices. The Catholic Church’s credibility when it witnesses to the dignity of women, or the inadmissibility of the death penalty, or the horror of sexual abuse, for example, is undermined when it fails to acknowledge its own role in these practices that violate human dignity. As I already noted, Church leaders have admitted to, and asked repentance of, such violations on numerous occasions, but it is jarring, then, when these historical realities are left unmentioned when the Church speaks about human dignity at the doctrinal level. The fear may be that mentioning that the Church has taught differently, or that it has failed to live up to its teaching, may undermine the Church’s teaching authority. But telling the truth about the victims of injustice, even when carried out with the complicity of the Church, would itself be a testimony to what the Church teaches about dignity.

Second, by leaving these inconsistencies in Church teaching and practice unaddressed in DI, the Vatican weakens its polemic against those traditionalists who resist recent magisterial teaching on dignity and its applications to issues like the death penalty or religious freedom. It would be better if the DDF had given an account of how earlier teaching on these and similar issues was meant to affirm certain timeless truths, but in light of the Church’s developing understanding on human dignity, the Church’s teaching must take on a different light. I offered examples of how this could be done regarding the issues of religious freedom, democracy, and the death penalty here.

Today, Giovanni Battista Bugotti is a colorful, although somewhat macabre, historical curiosity, a man who made his living in an “inhumane” practice, in the words of Pope Francis, that today should be absolutely inadmissible. His ghost, however, continues to haunt the Catholic Church, and will do so until the Church can give a better account of how it was complicit in, and how its teaching gave license for, practices it now recognizes as violations of human dignity.

I think you're touching on a really important point here. I thought DI dabbled in some revisionist history in its defense of the Church's historical championing of human dignity. Now, I agree with David Hart's argument that the very the modern understanding of human dignity came out of Christianity. But pretending that the Church (from the hierarchy to lay people) has not repeatedly and utterly failed at times to live up to our understanding of human dignity only discredits our witness.