This is the eighth in an occasional series exploring the contributions of different parts of the globe to the upcoming Synod on Synodality in October.

Last week, I provided an overview of the African continental document written in preparation for the Synod on Synodality this October, identifying the main themes in the document. It draws on the image of the Church as the “Family of God,” an image with deep roots in African spirituality and that had been used at the two African Synods in 1994 and 2009. Consistent with that theme, it calls on the Church to better integrate families in “irregular situations,” including those in polygamous marriages, but it remains silent on the topic of greater inclusion of LGBTQ persons. The document also calls for greater inculturation, the development of an authentic African Christianity, through listening to local cultures.

This week, in Part II of my focus on Africa, I will survey the delegates from Africa invited to the Synod. By my count there are 68 delegates from Africa. This is somewhat smaller than the delegation from Latin America and the Caribbean. The African delegation, however, includes a rather large number of bishops—over fifty—because each of the continent’s many episcopal conferences was allowed to send at least one bishop as a delegate. On the other hand, no Synod participants from the Roman Curia are from Africa, and only three African delegates were selected directly by Pope Francis. In addition, several religious and lay delegates and non-voting experts are from Africa. Luckily, I was able to identify all of the delegates from Africa.

As I noted last week, the boundaries of “Africa” in the eyes of the Vatican are ambiguous. The Assembly of the Catholic Hierarchy of Egypt (AHCE) is one of eight regional bodies making up the Symposium of Episcopal Conferences of Africa and Madagascar (SECAM), the regional episcopal conference that has organized the synodal process in Africa. Bishops and other delegates from Egypt, however, participated in the Continental Assembly for the Middle East, and so I am counting Synod participants from Egypt as belonging to the Middle East. For example, I included Patriarch Ibrahim Isaac Sidrak of Alexandria, the head of the Coptic Catholic Church, in my list of participants from the Middle East and not here.

Although none of the Roman Curia officials participating in the Synod are from Africa, that does not mean that Africa will be lacking prominent episcopal leaders. The well-known figures from the era of John Paul II and Benedict XVI—Cardinal Francis Arinze, Cardinal Robert Sarah, and Cardinal Peter Turkson, for example—have all more or less left the stage, and a new generation of African leaders have taken their place, although they are less well known in the United States.

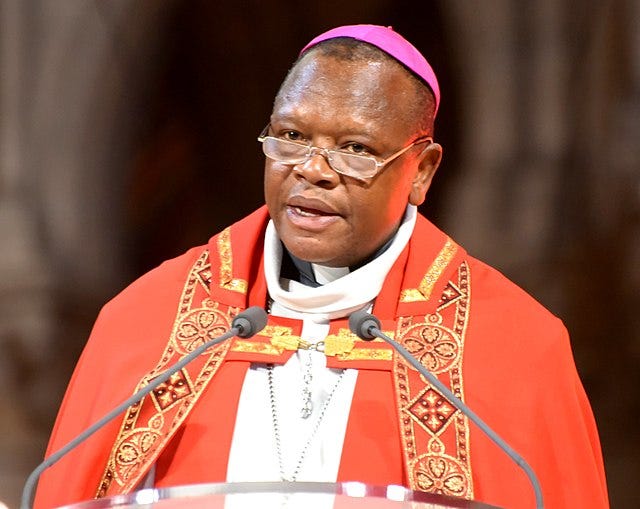

Among them is Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo Besungu, O.F.M.Cap., the Archbishop of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a huge country where Christians make up over 90 percent of the population, about one third of them Catholics. Cardinal Ambongo is the President of SECAM and will be attending the Synod in that capacity. Ambongo replaced Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya in Kinshasa, the latter of whom was a massively important figure in the DRC and was at one point considered a possible contender for the papacy. Pope Francis appointed Ambongo as archbishop in 2018 and named him a cardinal the following year. In 2020, Francis added him to the Council of Cardinal Advisers, a small group of cardinals from throughout the world who advise Francis on matters of governance. Cardinal Ambongo welcomed Pope Francis on his visit to the DRC earlier this year.

Two more recent appointments to the College of Cardinals will also be attending the Synod. The first is Cardinal Dieudonné Nzapalainga, C.S.Sp., the Archbishop of Bangui, in the Central African Republic (CAR). He was appointed as archbishop by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012 and then made a cardinal by Francis in 2016. Nzapalainga was the first cardinal born after the Second Vatican Council. Stephen Ameyu Martin Mulla, the Archbishop of Juba, in South Sudan, will be made a cardinal at a consistory later this month. Ameyu met with Pope Francis when the latter visited South Sudan this past February.

Although not (yet?) cardinals, two other church leaders attending the Synod are major figures in the African Church. Ignatius Ayau Kaigama is the Archbishop of Abuja, the capital of Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa. The president of the Nigerian episcopal conference from 2012 to 2018, he was appointed archbishop by Pope Francis in 2019. Jude Thaddaeus Ruwa'ichi, O.F.M.Cap. is the Archbishop of Dar-es-Salaam, the capital of Tanzania. Like Kaigama, he is the past president of his nation’s episcopal conference, and likewise was appointed archbishop in 2019.

Also attending the Synod will be the heads of two Eastern Catholic Churches from Africa. Cardinal Berhaneyesus Demerew Souraphiel, C.M. is the Metropolitan Archbishop of Addis Ababa and the head of the Ethiopian Catholic Church. The Ethiopian Catholic Church split from the much larger Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (which, like the Coptic Church in Egypt, is considered Oriental Orthodox because it rejects the Christological teachings of the fifth-century Council of Chalcedon) early in the twentieth century. Souraphiel was appointed archbishop in 1999 and made a cardinal by Pope Francis in 2015. Menghesteab Tesfamariam, M.C.C.J. is the Metropolitan Archbishop of Asmara, in neighboring Eritrea. He is the head of the Eritrean Catholic Church, which was separated from the Ethiopian Catholic Church in 2015.

Both Souraphiel and Tesfamariam have played the role of peacemaker. After decades of armed struggle, Eritrea had won independence from Ethiopia in 1991. War broke out between the two countries in 1998, however, over disputed borders; the conflict ended in 2000, but negotiations over the border continued until 2018, when peace was finally declared between the two countries. Tesfamariam, who had been the ordinary in Asmara since 2001 (and was elevated to archbishop in 2015) had pushed for this final peace deal. For his part, Souraphiel chaired the Peace and Reconciliation Commission after the war.

Unfortunately, peace between the two countries did not mean an end to violence and conflict. In Eritrea, the government is closely tied to the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church and has imposed repressive measures against other religions. In 2020, Cardinal Souraphiel was prohibited from entering the country for an event. In 2022, a Catholic bishop was held in prison for 75 days. In Ethiopia, tensions between the federal government and the regional government in Tigray, on the border with Eritrea, broke into open conflict in 2020, with Eritrea intervening on the side of the Ethiopian government. The conflict, which ended in 2022, was a humanitarian catastrophe, with thousands of civilians killed, many more displaced, and others dying from famine. Throughout the war, Cardinal Souraphiel advocated for peace, and he later supported the 2022 peace agreement. Markos Ghebremedhin, C.M., the Apostolic Vicar of Jimma-Bonga, who will also be attending the Synod, has also been an advocate for peace in Tigray.

The bishops attending the Synod have played the role of peacemaker throughout Africa. For example, Cardinal Ambongo from the DRC has worked for peace in that country’s eastern regions and criticized the international community for its lack of action to help end the conflict. The conflict in the North Kivu and South Kivu provinces has stretched on since 2004 and involves several armed groups, including the armed forces of a number of the DRC’s neighbors. Ambongo’s episcopal colleague Marcel Utembi Tapa, the Archbishop of Kisangani, has also been an advocate for peace during this period.

Along with Cardinal Nzapalainga, Nestor-Désiré Nongo-Aziagbia, S.M.A., the Bishop of Bossangoa, has worked for peace during the civil war in the CAR. The war, which began in 2012, at first pitted the Muslim Séléka rebel movement against the government, and after the latter collapsed in 2013, the mostly Christian anti-Balaka militia emerged to combat Séléka. For his part, Nongo-Aziagbia claims he was nearly beheaded by Séléka militants in 2014. In neighboring Chad, Nicolas Nadji Bab, the Bishop of Laï, has mediated a local conflict between herders and farmers. Andrew Nkea Fuanya, the Archbishop of Bamenda in Cameroon, has called for peace in that country’s separatist conflict.

Since 2020, there have been eight military coups in six nations in West and Central Africa: Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Sudan, and most recently Gabon. Common factors include persistent Islamist insurgencies, weak states, and fragile democratic institutions. Several Synod attendees have spoken in response to this trend. Vincent Coulibaly, who replaced Cardinal Sarah as the Archbishop of Conakry in Guinea, has played a mediating role in the aftermath of that country’s coup in 2021. Earlier this year, Archbishop Gabriel Sayaogo of Koupéla led the faithful in a prayer for peace and social cohesion after last year’s coup in Burkina Faso. In Gabon, Archbishop Jean-Patrick Iba-Ba of Libreville had called for prayer and penance in preparation for elections this past August 26, but military officers annulled the election results only four days later.

Other countries have been more successful in preserving their fragile democracies over the past several years, and ecclesial leaders who will be present at the Synod have been outspoken in support of the democratic process. For example, in Côte d'Ivoire in West Africa, Marcellin Yao Kouadio, the Bishop of Daloa and the president of the nation’s episcopal conference, has been an outspoken critic of political corruption and “tribalism.” Ignace Bessi Dogbo, the Archbishop of Korhogo chosen by Pope Francis to attend the Synod, has also promoted reconciliation and respect for the democratic process in Côte d'Ivoire.

Edward Tamba Charles, the Archbishop of Freetown in Sierra Leone, pled for peace in the runup to that country’s elections this past June. He is the president of the Inter-Religious Council of Sierra Leone, an interfaith organization that promotes civic education. Similarly, Emmanuel Kofi Fianu, S.V.D., the Bishop of Ho, Ghana, serves on the board of the National Peace Council, a group established by the legislature in 2011 to promote cooperation and peace.

In Liberia, Anthony Fallah Borwah, the Bishop of Gbarnga, has called for civility ahead of this October’s elections. In Kenya, where political tensions and even sporadic violence have broken out after elections held last month, following protests in the months before the election, Archbishop Martin Kivuva Musonde of Mombasa and Archbishop Anthony Muheria of Nyeri have both called for peace and dialogue.

Tensions between Christians and Muslims in Africa can be a source of conflict, as in the CAR, but they often intersect with ethnic and socioeconomic tensions. The dynamics can also be significantly different in countries that are predominantly Muslim and those where the population is more evenly divided.

For example, Cardinal Cristóbal López Romero, S.D.B. is the Archbishop of Rabat, in Morocco, where Muslims make up 99 percent of the population. Here, according to López Romero, the Church is called to be a “a sign and sacrament of the Kingdom of God” through its mission of “encounter and dialogue.” López Romero, a member of the Salesians, is originally from Spain; he worked in Paraguay and eventually became the provincial there, then worked in Morocco from 2003 to 2011, when he was appointed the Salesian provincial in Bolivia. In 2018, Pope Francis appointed him as the archbishop of Rabat, and the pope made him a cardinal in 2019. That year he welcomed Francis on his visit to Morocco.

In Mali, where religion has been a source of conflict, Hassa Florent Koné, the Bishop of San, has tried to engage in interreligious dialogue in the spirit of Pope Francis’s 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti. In the CAR, Cardinal Nzapalainga, along with Muslim and Protestant leaders, formed the Interfaith Religious Platform of the Central African Republic to promote peace.

Kenya is a majority Christian nation, but in the eastern part of the country, along the Indian Ocean, Muslims are more numerous. In Mombasa, the major city along the coast, Archbishop Kivuva has promoted interreligious dialogue and has sought to teach Christians that their Muslim neighbors should not be identified with radical terrorist groups like al-Shabaab.

The African representatives to the Synod have also been outspoken on ecological issues, drawing on Pope Francis’s teachings in his 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’. The African continent has suffered dramatic effects as a result of climate change, such as the desertification of the Sahel region (a process that contributes to some of the conflicts already mentioned), but also suffers from deforestation and pollution. For example, Cardinal Ambongo from the DRC has condemned the reckless extraction of natural resources in his country, often used to fund armed groups, and has praised Pope Francis’s ecological vision.

Liborius Ndumbukuti Nashenda, O.M.I., the Archbishop of Windhoek, Namibia, in Southern Africa, issued a message to his archdiocese calling for care for creation and the responsible use of natural resources. In Ghana, the bishops, including Synod delegate Archbishop Charles G. Palmer-Buckle of Cape Coast, launched a five-year Laudato Si’ Action Program in 2021, including a massive tree-planting drive. Archbishop Kaigama of Abuja, Nigeria also launched a tree-planting program in his archdiocese in August of this year.

Although the African episcopal delegates have followed Pope Francis’s lead on ecological issues, they have not done so regarding the inclusion of LGBTQ persons in the Church. As I noted last week, earlier this year, Francis criticized the criminalization of homosexuality, a reality in many African nations. In contrast, for example, Cardinal Souraphiel from Ethiopia has supported that country’s law criminalizing homosexuality. Bishop Kouadio from Côte d'Ivoire has called for its criminalization in a country where it is legal. As Archbishop Palmer-Buckle has noted, many Africans perceive LGBTQ rights as part of a Western agenda that has been imposed on the continent in exchange for development aid. It will be worth watching how the conversation unfolds at the Synod, where the issue will not be the morality of same-sex relations, but rather how the Church can include LGBTQ persons in the life of the Church.

Although there may be contentious issues at the upcoming Synod, several of the attending African bishops have been vocal in their support for synodality and the need for structural changes in the Church. Indeed, at the second African Synod in 2009, Archbishop Palmer-Buckle from Ghana suggested that the laity, and especially women, should have a greater role in the synodal process, a change that Pope Francis has made a reality at this year’s Synod:

I'd like to believe that if Rome would evaluate the contribution of the auditors, the lay men and women and the rest, we might probably move from a synod of bishops into something more like a pastoral congress of the universal church.

In Mozambique, Inácio Saure, I.M.C., the Archbishop of Nampula and president of that nation’s episcopal conference, has experience with a such a gathering at the national level, having launched Mozambique’s fourth National Pastoral Assembly in May of this year. Ignatius Chama, the Archbishop of Kasama in Zambia, has tried to promote greater lay participation in the ministries of the Church, and Archbishop Ameyu from South Sudan has also called for greater participation from the laity and young people.

In terms of changing leadership styles, Bishop Fanu from Ghana has said that the priesthood should be a “service in humility.” Archbishop Kaigama has called for a synodal style of leadership like that practiced in the early Church. In more theological terms, Ildo Augusto Dos Santos Lopez Fortes, the Bishop of Mindelo in the island nation of Cape Verde, has noted that synodality means we must recognize the Church as a communion whose members have been given a diversity of charisms. Similarly, Gabriel Mbilingi, C.S.Sp., the Archbishop of Lubango in Angola, has also spoken of the Church in terms of the Body of Christ, where each member has a part to play.

Lúcio Andrice Muandula, the Bishop of Xai-Xai in Mozambique, has argued that the synodal process will be transformative for Africa. Bishop Muandula is a member of the Preparatory Commission appointed by the Vatican in advance of the Synod, and also was appointed one of the Synod’s president-delegates by Pope Francis. Muandula greeted Francis on the latter’s visit to Mozambique in 2019. Similarly, Cardinal Ambongo has called the synodal process “a Kairos for renewal of the Church in Africa.” That being said, Archbishop Nkea from Cameroon has also suggested that Africa has something to offer the world through the synodal process, which has given the African Church a voice. At a practical level, Archbishop Nkea has also spoken about the difficulties of implementing the synodal process at the local level.

Reflecting the diversity of roles in the Church, the African delegation includes a number of noteworthy priests, religious, and lay people. They include Fr. Rafael Simbine Junior, a priest from Mozambique and the Secretary General of SECAM, who has been instrumental in organizing the synodal process for the African continent. The secretaries general of three of Africa’s regional episcopal conferences will also be present. They include: Fr. Vitalis Chinedu Anaehobi, a priest from Nigeria and the secretary general of the Reunion of Episcopal Conferences of West Africa (RECOWA); Fr. Michel Guillaud, a priest originally from France but working in Algeria, the secretary general of the Regional Episcopal Conference of North Africa (CERNA); and Fr. Anthony Makunde, a priest from Tanzania, the secretary general of the Association of Member Episcopal Conferences in Eastern Africa (AMECEA). Fr. Makunde will be a non-voting expert at the Synod, but the others will be voting delegates.

In terms of religious, two superiors from Africa will be present at the Synod. Sr. Elysée Izerimana, Op. S.D.N. from Burundi is the General Councilor of the Working Sisters of the Holy House of Nazareth. Fr. Gebresilasie Tadesse Tesfaye, M.C.C.J. from Ethiopia is serving his second term as the superior general of the Comboni Missionaries of the Heart of Jesus. Fr. Tesfaye previously served as the provincial for Ethiopia and as the general councilor for the order.

In addition to these superiors, a number of other religious from Africa will be present. For example, Sr. Paola Nelemta Ngarndiguimal, S.P.C., from Chad, is the Provincial Superior of the Sisters of Charity of Saint Jeanne-Antide Thouret for Central Africa and works with impoverished women and children in her home country. She will be a non-voting expert at the Synod. Sr. Solange Sahon Sia, N.D.C., a member of the Congregation of Our Lady of Cavalry, is the Director of the Centre for the Protection of Minors and Vulnerable Persons, located at the Catholic Missionary Institute of Abidjan, the capital of Côte d'Ivoire. Sr. Sia was the first woman in Côte d'Ivoire to receive her doctorate in theology. Sr. Marie Solange Randrianirina, F.S.P. is a member of the Daughters of St. Paul from Madagascar.

The only lay person from the African delegation (besides one theologian mentioned below) is Dr. Sheila Leocádia Pires. Dr. Pires is from Mozambique but works in South Africa for the Southern African Bishops' Conference, where she serves as a communications officer. She is a producer and presenter for Radio Veritas, a Catholic radio station. At the Synod, she will be part of the Commission for Information, which is responsible for communicating with the press during the Synod.

Saving the best for last, the African delegation includes a number of noteworthy theologians. Certainly the best known in the United States is Fr. Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator, S.J. from Nigeria. Until last month, Fr. Orobator was the President of the Jesuit Conference of Africa and Madagascar, but this fall he begins his appointment as the Dean of the Jesuit School of Theology at Santa Clara University in California. He had previously taught at Hekima University College in Kenya, St. Augustine College of South Africa, and Marquette University in Milwaukee. Fr. Orobator’s work has focused primarily on the inculturation of African theology and ecclesiology. He has been active in the Association of African Theologians (AAT) and theological societies in the United States. Fr. Orobator has been involved throughout the synodal process in Africa and has spoken on the need for a “listening Church.”

Also noteworthy is Sr. Josée Ngalula, R.S.A. from the DRC, the first African woman to be appointed to the Vatican’s International Theological Commission. She is a member of the Faculty of Theology at the Catholic University of Congo and Director of the Observatory on Religious Violence and Fundamentalism at that university. A founding member of the AAT, she has also been involved with the Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church project. Her work focuses on religious violence and violence against women. Speaking about synodality, she has said that it has links to both African culture and the practices of religious congregations of women.

Fr. Paul Béré, S.J. is a member of the faculty at the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome and the winner of the Ratzinger Prize in 2019, awarded by Pope Francis to a leading Catholic theologian. Although a biblical scholar, Fr. Béré has also called for the greater inculturation of African theology and Christianity.

Sr. Anne Béatrice Faye, C.I.C. is a member of the Congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of Castres from Senegal but currently working in Burkina Faso, at a high school in the town of Pouytenga. Sr. Faye is a member of the AAT and also a member of the editorial board of the international journal Concilium. She is serving as a non-voting expert at the Synod. Nora Kofognotera Nonterah from Ghana is a Lecturer in Religious Studies at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology. Her work has focused on interreligious dialogue and faith formation, among other topics. Sr. Ester Maria Lucas, F.C. is a member of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul and a theologian who helped write the African continental document.

Among the bishops, Archbishop Dabula Anthony Mpako of Pretoria, South Africa is a serious intellectual. He studied pastoral counseling at Loyola University in Chicago, writing his thesis in 1994 on “Decolonizing the African Psyche” and drawing on the work of Frantz Fenon and Steve Biko. He went on to be a co-founder of the African Catholic Priests' Solidarity Movement, a group of priests that claimed the Church in South Africa was too Eurocentric and needed to be grounded in the realities of the Black community. Archbishop Mpako was involved in the synodal process for the Southern Africa region. Likewise, Bishop Kouadio has written a theological work on the need for inculturation in an African context.

In contrast, Lucius Iwejuru Ugorji, the Archbishop of Owerri in Nigeria, has been convincingly accused of plagiarizing parts of his 1984 doctoral dissertation at the University of Münster, in Germany. The dissertation, written on the ethical principle of double effect and directed by Bruno Schüller, includes passages without citations by numerous authors, including some known to many readers, such as the theologians Lisa Sowle Cahill and Richard McCormick, and the philosopher Alan Donagan. Ugorji had served as Bishop of Umuahia since 1990 until he was appointed to Owerri in 2022. It was in that year that he was accused of plagiarism, and the University of Münster has yet to resolve the case.

Plagiarists aside, the African delegation to October’s Synod includes experienced leaders, peacemakers, advocates for synodality, and skilled theologians. They are bound to make a significant impact at the Synod. In some cases, such as the role of LGBTQ persons in the Church, they may play a more controversial role. In others, such as developing synodal forms of leadership among the clergy and laity alike and linking synodality with the pursuit of peace, they will find common cause with other delegates from around the world.