One of the ideal characteristics of theology, according to Pope Francis in his apostolic letter Ad Theologiam Promovendam and his more recent remarks at an international theological congress, is interdisciplinarity (or “transdisciplinarity”). I’ve certainly tried to embody this trait in my own theological work over the years, especially by bringing theology into dialogue with the social sciences.

One of the challenges of doing interdisciplinary work, however, is that it can be difficult to keep up with the literature in your own field as well as you would like. Keeping up knowledge in other disciplines sufficient to engage in meaningful dialogue takes time and effort. In addition, there’s certainly little time to revisit texts read long ago, except for readings used for a class or texts central to your own work.

Even so, I recently decided to reread the 20th-century theologian Henri de Lubac, S.J.’s classic work The Mystery of the Supernatural. When I was in graduate school, The Mystery of the Supernatural, along with de Lubac’s Surnaturel and Augustinianism and Modern Theology, were formative in shaping me as a theologian. But I’ve grown and developed as a theologian in the nearly twenty years since then, and so I wanted to revisit de Lubac’s work and look at it through different eyes.

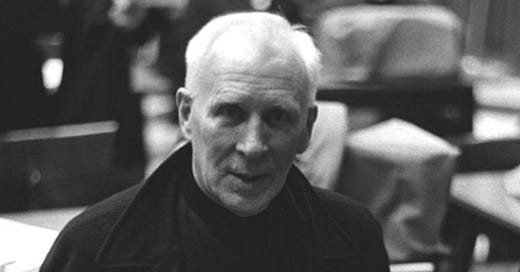

Before getting to The Mystery of the Supernatural, I want to briefly summarize de Lubac’s life for readers who may be unfamiliar. De Lubac joined the Jesuits in 1913 and studied philosophy in England and on the island of Jersey from 1913 to 1923, with a pause from 1914 to 1919, when he served in the French army during the First World War. From 1924 until his ordination in 1927, he studied in theology in England and later at the Jesuit house Fourvière in Lyons. His first book, Catholicism: Christ and Common Destiny of Man, was published in 1938 to great acclaim. In it, he argued for the centrality of the social or communal dimension of the Catholic faith in response to the individualistic, privatizing tendencies that had crept into modern Catholicism.

The publication of de Lubac’s fourth book, Surnaturel: Études, placed him at the center of controversy and eventually changed the course of Catholic theology. In this work, de Lubac argued that the Church Fathers and the great medieval scholastic theologians, including St. Thomas Aquinas, had held that human beings have a natural desire for God as their ultimate fulfillment (or “final end”), but also that humankind cannot achieve this ultimate fulfillment through their own efforts, but only through the unmerited grace offered freely by God.

This was a controversial thesis because later Thomists insisted—appealing to the authority of Aquinas—that if humankind had a natural desire for this supernatural end, that would mean that God owed this fulfillment to human beings (because God would not make a creature with a nature lacking the necessary capacities for achieving its natural end). Instead, they argued that God could have created humankind with a “pure nature,” that is, with a nature fulfilled by the kind of knowledge of God attainable through our natural powers. In the cosmos as it actually exists, however, God graciously and supernaturally elevated human nature so that it is now only ultimately fulfilled by a supernatural end, union with God. These later Thomists believed that this hypothesis ensured the gratuity of our supernatural destiny.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Window Light to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.