Doing Casuistry with Pope Francis and The Good Doctor

Accompaniment and Asking the Right Questions

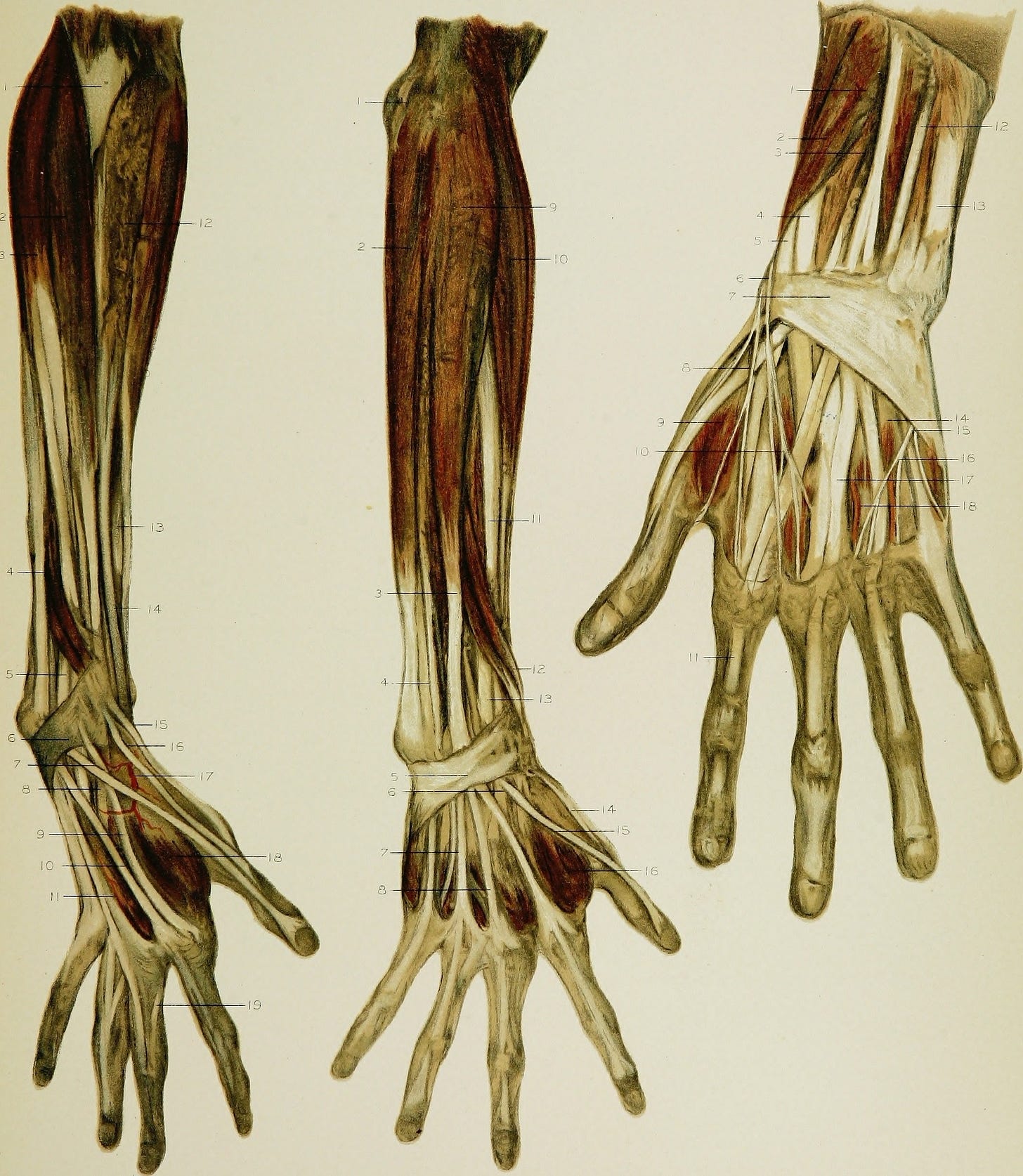

A few weeks ago, a bit of dialogue from the ABC show The Good Doctor stuck with me. Here is the background. Drs. Shaun Murphy and Alex Park come across a car accident and find an injured woman in the car. While Dr. Park is treating her, Dr. Murphy finds her husband, who had been thrown from the car, in some nearby woods. The man was bleeding heavily from his radial artery, the blood vessel that feeds the forearm and hand, and he had already lost circulation in his hand. Dr. Murphy feared that, because of the lack of circulation to the hand, toxins could leak from his hand to his heart and kill him if the hand was not amputated. So Dr. Murphy performed the amputation.

Some time later, the man sues Dr. Murphy for malpractice, arguing that the lack of circulation could have been caused by vasospasm, a sudden contraction of the arteries, which can be caused by trauma. The vasospasm could have been treated by an ambulance crew that had just arrived on scene at the time Dr. Murphy amputated the hand, which would have restored circulation and made the amputation unnecessary. (As a theologian, I make no claims regarding the accuracy of the medical claims here!)

In the scene that caught my attention, Joni DeGroot, the attorney Dr. Murphy has hired to defend him against the malpractice suit, walks in on Dr. Murphy testing the lactate levels in the man’s hand; elevated levels would show that the hand had already become toxic and that therefore the amputation was justified (Hopefully I am not violating copyright here!):

DeGroot: Stop! Stop! Stop!

Murphy: I’m about to test the lactate levels in Bob’s hand. This will prove definitively if I was right to amputate.

DeGroot: No, this will tell you nothing.

Murphy: Medically, it will.

DeGroot: Legally, morally, this’ll tell you nothing.

Murphy: This test will tell me the truth.

DeGroot: <Scoffs>

Murphy: Was that a laugh?

DeGroot: It was a scoff.

Murphy: Why would you scoff at the truth?

DeGroot: What truth?

Murphy: There’s only one. There’s a single, correct answer to any question.

DeGroot: But there are a lot of questions. You’re asking, “What was the right thing to do then, given what you know now?” Which is a stupid question.

Murphy: I don’t like to use the word “stupid.”

DeGroot: “Desperate” then. For an answer. But whatever that test says, we have to share it with the other side. If it goes the way you want, we will definitely win your case. If it goes the other way, we will definitely lose your case. But neither result will tell you if you did the right thing, given what you knew at the time.

This bit of dialogue is a fantastic explanation of what we mean by “casuistry,” the process of thinking through moral problems by examining specific cases and their concrete circumstances. In DeGroot’s words, it is focused on “if you did the right thing, given what you knew at the time.” Casuistry is fundamental to legal practice, but as DeGroot points out, it is also a way of gaining moral knowledge. The Catholic tradition of casuistry developed among moral theologians primarily to help priests guide penitents in the sacrament of confession, but has also come to be used in other settings, especially medical ethics.

The dialogue is fascinating because DeGroot’s apparent scoffing at “the truth” (her question “What truth?” even echoes Pontius Pilate’s pointed question at the Passion, “What is truth?”) and her argument suggesting “it depends on how you look at it” illustrate how casuistry came to have a bad reputation and to be dismissed as sophistry or moral laxity. Yet DeGroot is not scoffing at truth itself, but rather at a partial and incomplete notion of truth. Casuistry helps makes clear the truth about human actions, a kind of truth that can’t be discovered in a laboratory.

Although moral theologians do not work in laboratories, we often try to work under the conditions that a laboratory is meant to simulate, where we have direct, objective access to the phenomena to be explained, free from the interference of the complicating factors of the “real world.” You might say that we try to adopt a “God’s-eye point of view” on good and bad, right and wrong.

As Catholics, we believe that God created us with the capacity to know good and bad, right and wrong, and to use that knowledge to guide our decisions, and so it is not as if that “God’s-eye point of view” is completely alien to us. We are finite creatures, however, thrown into the world where we must act, not just with a finite knowledge of the situations in which we find ourselves and the consequences of our potential choices, but also marked by sin and its effects. Our struggle to do good and avoid evil is an existential struggle, not something we can conduct from a “God’s-eye point of view.” And casuistry is a form of moral reasoning that helps us think through right and wrong existentially—what was right or wrong at that time, in that place—without breaking down into subjectivism. Casuistry suggests we have to jump into the messiness of the world to understand the truth, rather than try to abstract ourselves out of it.

A few days ago, Pope Francis gave an address to a conference held at the Alphonsian Academy, or Alphonsianum, in Rome in which he offered some remarks on moral theology. Unfortunately for me and this essay, in those remarks, he denounced “casuistry.” It is clear, however, that he is using the term in the pejorative sense rather than in the more authentic sense of helping or accompanying someone as they address the moral problems they confront in an existential moment. After all, Francis uses the address to honor St. Alphonsus Liguori, the greatest of the early modern casuists!

What Pope Francis seems to be denouncing is form of casuistry that gets bogged down in fine distinctions and complex formulas but that loses touch with the existential realities of people’s lives. He refers to it as “a cold morality, theoretical morality [una morale da scrivania, literally “a morality of the desk”].” Pope Francis goes on to praise the characteristics of what I am calling authentic casuistry:

Every moral-theological proposal has, in the final analysis, this foundation: the love of God is our guide, the guide of our personal choices and our existential journey. As a consequence, moral theologians, missionaries and confessors are required to enter into a living relationship with the People of God, engaging in particular with the cry of the least, to understand their real difficulties, to look at existence from their perspective, and to offer them answers that reflect the light of the eternal love of the Father.

This is also the approach that Pope Francis takes in Amoris Laetitia, where he speaks of the Church accompanying people as they work through the challenges of family life.

The scene from The Good Doctor ends with a bit of sentimentality:

DeGroot: So the real question here is: Do you believe in that test more than you believe in me? Why?

Murphy: Why am I doing what you just asked me to do?

DeGroot: Why do you have so much confidence in me? I’m a lawyer with OCD. I work out of a closet. I was late to the only meeting you had with me. Why do you trust me more than the test?

Murphy: Because the test doesn’t care.

DeGroot: That’s a good answer.

At first I groaned, or maybe scoffed, as their conversation shifted from the deeply philosophical consideration of truth and the practical considerations of how to win Dr. Murphy’s case to a conversation about their relationship with each other. But on second thought, I now realize it is essential to DeGroot’s role as a casuist that she is an advocate for Dr. Murphy as he faces this legal challenge, just as Pope Francis points out that the role of the moral theologian is to guide people on their existential journey in the light of God’s love. Later in the address Francis makes this point even more clearly:

Problems are solved by walking ecclesially, as the people of God. And to walk with people in the moral state in which they find themselves. Walking with them and looking for a way to solve their problems, but walking, not seated like doctors with a finger raised to condemn without concern.

As DeGroot pointed out to Dr. Murphy, the results of his lab test may have absolved him, but they also may have condemned him. What they couldn’t do was address the situation in which he found himself the night he and Dr. Park came across the car accident, or the situation in which he finds himself now, faced with a malpractice suit. What he needed was someone to walk with him and help him look for a way to solve his problem, just as the role of a moral theologian is primarily neither to absolve nor to condemn, but rather to accompany and guide people on their journey toward divine love.

Announcements…

Last week, the Window Light newsletter surpassed one hundred subscribers, and it has continued to grow! Thank you to all of you for subscribing, and for your support. When I started the newsletter, I didn’t know what to expect, but I am grateful to all of you, subscribers and readers. Please continue to share the newsletter with friends and colleagues you think might enjoy it.

Of Interest…

Paul Fahey also offers some brief comments on Pope Francis’s address on moral theology at the former’s Substack newsletter Pope Francis Generation.

Massimo Faggioli, writing at La Croix International, reflects on the current state of academic theology in the United States, in part in response to my essay published here at Window Light and picked up by America. Near the end of the essay, Faggioli makes the excellent point that, not only must we ask if it is possible to be a theologian outside of academia, but also if it is possible inside academia, given the increasing professionalization and technocratic mindset in higher ed. He also notes that the apparent decline of theology at Catholic universities opens the door to “self-trained and self-appointed fortune-tellers masquerading as theologians all over the internet.” The theologian Elissa Cutter, however, pointed out to me in a comment on Facebook, drawing on her research into 17th-century French nuns, that new forms of theology may require forms of theological education that are not recognized by more credentialed authorities.

On March 20, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee on Doctrine issued a doctrinal note regarding medical interventions for gender dysphoria, rejecting gender-affirming medical treatments for transgender persons. Katie Collins Scott at the National Catholic Reporter has an excellent article on the document, including comments from theologians and others both supportive and critical of the USCCB document.

Coming Up…

Some time next week, Window Light will publish an interview with Jason King and M. Therese Lysaught, the Editor Emeritus and Editor, respectively, of the Journal of Moral Theology on their work as editors and the future of theological publishing. This is the first of what I envision to be an ongoing series of interviews published in the newsletter. Be sure to subscribe and tune in next week!