Yesterday, Heidi Schlumpf of the National Catholic Reporter published an excellent article reporting on the recent annual conventions of the Catholic Theological Society of America (CTSA), College Theology Society (CTS), and Academy of Catholic Hispanic Theologians of the United States (ACHTUS). Schlumpf emphasizes that at all three meetings, concerns about the future of Catholic theology as an academic discipline were palpable, especially in light of recent university closings, the elimination of theology programs and faculty positions, and the financial woes of many Catholic colleges and universities.

Back in February, when I launched this newsletter, I wrote my own reflections on the future of Catholic theology in the context of the elimination of the theology program at Marymount University, where I had been employed, and my resignation from the university’s faculty (the article was later picked up by America Magazine). I would like to think that my article hit a nerve and has had some impact on the conversations reported by Schlumpf, but regardless, anxieties about the current state of affairs in the discipline and calls for creativity in developing new ways of doing Catholic theology and building a scholarly community are bubbling up among theologians nationwide.

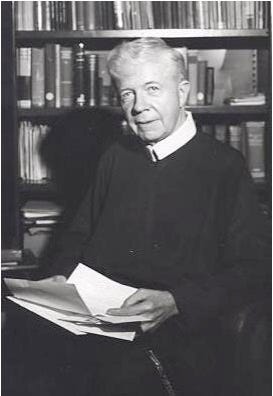

Although the headline emphasizes the anxieties experienced by Catholic theologians today, in the article, Schlumpf notes that the presidents of both the CTSA and the CTS, Francis Clooney, S.J. and Brian Flanagan, respectively, expressed hope for the future of theology. The CTSA, in particular, has already begun developing creative initiatives intended to respond to the changing realities on the ground. For example, at the annual convention earlier this month, the CTSA passed a resolution urging its board to institute measures that would facilitate the continued participation of scholars impacted by institutional closures or the elimination of programs, such as reduced membership dues and conference fees.

Such measures are necessary and invaluable for scholars who have lost the institutional support of a university, but they are also reactive rather than adaptive. The CTSA, however, has also been experimenting with other ways to build collegiality and share scholarship outside the annual convention that take advantage of changing technologies and that better need the changing needs of theologians, both university-based and not. For example, in April, the CTSA hosted a virtual event on artificial intelligence and the theology classroom, and later that month held another virtual event where members discussed a proposal outlining how the society could divest from fossil fuels (which I wrote about here; as Schlumpf notes, the CTSA passed this measure at the recent meeting).

The CTSA is not the only professional society holding smaller, virtual events. For example, many of the interest groups of the Society of Christian Ethics (SCE) hold virtual “midterm meetings” during the summer where scholars with interests in fields like health care ethics, conflict and peace, and university ethics can share their scholarship and discuss ongoing developments in their fields.

In my February article, I highlighted professional conferences as one area where theologians would need to adapt to the changing needs of theologians, focusing particularly on the inclusion of theologians outside of academia and evolving perspectives on academic conferences in light of digital technology, COVID-19, and climate change, so it is encouraging that real changes are already taking place.

While noting the need for the theological profession to adapt to changes in higher education, both Clooney and Flanagan also pointed out that the profession has been evolving throughout the life of both societies. I wrote about some of these changes myself last week in my reflections on teaching theology to today’s undergraduate students. I focused particularly on the growth of theology as part of the curriculum for undergraduate students at Catholic colleges and universities. The College Theology Society was formed as a professional society for the professors, mostly lay, who taught in these programs. The Catholic Theological Society of America, on the other hand, brought together professors from seminaries and graduate programs. These distinctions have blurred over time, however.

Clooney described this evolution in his presidential address at the annual convention (I am here citing Schlumpf’s article):

Clooney traced what he saw as three eras of the 77-year-old Catholic Theological Society of America: In the beginning, during the "seminary era," all its members were clerics, until the 1960s when lay men and women were admitted. What followed was a "golden era" of symbiosis between colleges and universities and the professional society.

"That era is, in a sense, over with," Clooney said, adding that the CTSA is entering a third era, which should proceed "without nostalgia for the first or the second." It is both "exciting and terrifying" to imagine what this third era will be like, he said.

Flanagan (my friend and former colleague at Marymount) likewise described a kind of fall from a golden age:

"Theology as many of us have known it is dying," Flanagan said in his presidential address. "We live in a very different world than that of the founders of the CTS in 1954, and even in a different world for those of us who have only been present for the past few decades."

CTS was created for scholars who "only" taught undergraduate religion, at a time when the CTSA was limited to theologians — all clerics — who taught in seminaries.

Gone are the days when "students routinely took three, four or more courses in religion just to graduate and when theologians were not just needed but valued," said Flanagan of Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia, which recently cut nine majors, including theology.

What is striking about both addresses, aside from the shared recognition that Catholic theology is entering a new age, is the sense that the relationship between the Catholic university as an institution and the discipline of theology has shifted. Gone are the days of “symbiosis,” when theologians were “not just needed but valued.” Both suggest obliquely that at many, although by no means all, institutions today, there is an ambiguous, if not hostile, relationship between ostensibly Catholic universities and theology programs. Administrators and sometimes, tragically, fellow faculty have adopted a “neoliberal” educational model that values career preparation and revenue generation above humanistic education. Flanagan, for example, noted the “dramatic weakening of Catholic and other religious identities in our institutions as administrations and boards of trustees pursue an increasingly corporatized and increasingly desperate competition for customers — sorry, students."

The battle for the soul of Catholic universities is still one that is worth fighting, as exhausting as it is. At the same time, the increasing tension between theology and the academy creates an opportunity for exploring ways of doing theology outside the academy. At a session on the future of the society at the CTSA’s recent meeting, participants expressed a desire for greater engagement with the Church and with the world (a reference to David Tracy’s well-known account of the three audiences of theology: academy, Church, and world). I think the future will see not just greater engagement with the Church and the world on the part of theologians, but a growing number of theologians living out their vocations while employed in the Church and in the world outside of higher education. These theologians will necessarily live out their vocations without the same institutional support many theologians today receive from universities, and so it is imperative that the theological guild nurture other forms of support and collegiality.

Schlumpf’s reporting on ACHTUS’s annual meeting highlights a different issue, one that is in many ways positive: the growth in the number of U.S. Hispanic theologians, reflected in the membership of the group. Although this is good for ACHTUS, as incoming president (and longtime friend) Ramón Luzárraga points out, these younger scholars are entering an academic world where the number of opportunities for full-time, tenure-track employment are dwindling. Likewise, Luzárraga adds, U.S. Hispanic theology (and one might add Black theology and Asian-American theology) remains somewhat on the margins of the theological academy (a theme I also discussed in a response to an article by Hoon Choi here).

So, we are faced with a situation where, on the one hand, the field of Catholic theology is being enriched by a growing number of young Hispanic, African-American, and Asian-American scholars, but these theologians face an increasingly precarious job market and a university environment increasingly ambivalent or hostile toward our discipline. As Flanagan noted in his address, more privileged members of the theological guild, whether because of their social identity or their institutional status, have a responsibility to empower these scholars and ensure they have a place in institutions of higher education and in professional societies. At the same time, it also seems likely to me that some of the most creative new forms of living out the theological vocation and developing collegial networks will emerge out of the struggle for these voices to be heard, in response to this growing institutional crisis.

Of Interest…

The Vatican office organizing the worldwide Synod on Synodality process on Tuesday released the instrumentum laboris, or working document, that is a synthesis of the seven continental documents produced over the past several months as a result of synodal gatherings around the world. The instrumentum laboris will be the starting point for discussions when bishops from throughout the world gather in Rome for the first session of the Synod in October. The document can be found here. I hope to write some reflections on the instrumentum laboris in the near future.

Religion News Service has an interesting article focusing on how organizations of sexual abuse survivors and advocates are pushing for the upcoming Synod as an opportunity to promote awareness and accountability in the Church. They see the Synod as an opportunity to promote structural changes in the Church that can promote greater transparency and accountability.

Likewise at RNS, Mark Silk has an article analyzing how religious identity in the United States is increasingly a matter of personal choice rather than tradition or family upbringing, a shift that lies behind the growth in “nones,” or people without any religious affiliation. Theologians ought to recognize this not just as a sociological reality but as the context in which we do theology today.

Coming Soon…

In the near future, I hope to do a different kind of post, one featuring advice from editors on how to improve the chances of your manuscript getting accepted to an academic journal. If you have experience as an editor or another staff role with a theological journal and would like to participate, please contact me at: matthew_shadle@outlook.com. Thanks to M. Therese Lysaught for the suggestion!

Thanks for this! Heidi does great work and I hadn’t seen that she took this on after these conferences. Very helpful summary and reflections.

I just noticed that in the original version of this, at one point I referred to Clooney and Flanagan's presidential addresses as "essays." That is now fixed in the online version. Unfortunately, I can't go back and fix it in the emails that already went out this morning!