Death No Longer Has Power Over Him

Commentary on the Readings for the Thirteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Many years ago, the parish I was attending was planning the renovation of the entire worship space and entry area of the church. During the design phase of the renovation process, different committees were established to help design different aspects of the worship space, and I was asked to be on the committee designing the baptistry, particularly the baptismal font.

To help us with the process, we looked through a catalog of different baptismal fonts, looking for one that would fit the ambiance and character of our church. Having never been involved in church design or renovation before, it struck me as funny that you would pick out the different elements from a catalog, a little bit of consumerism intruding into the life of the Church.

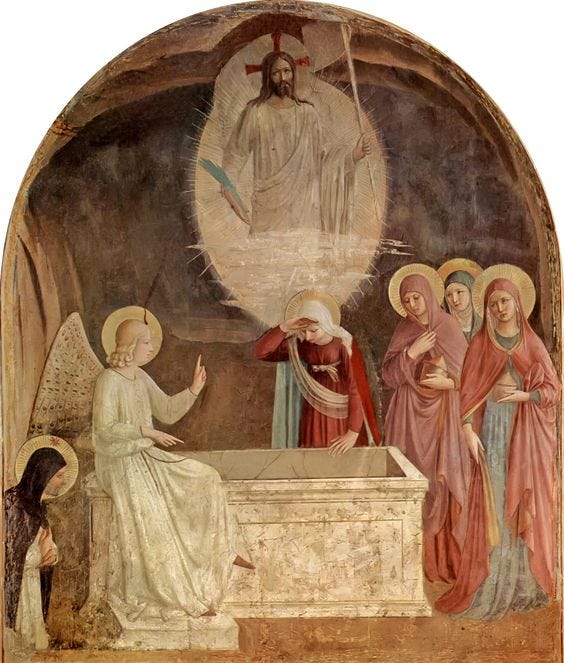

One of the options got our attention. The font was crafted in the shape of a life-sized sarcophagus and designed to be filled with water. During a baptism, the priest or deacon would dip the person being baptized down into the sarcophagus, and then raise them back up. This design was meant to accentuate a point made by the Apostle Paul in this Sunday’s second reading:

Are you unaware that we who were baptized into Christ Jesus

were baptized into his death?

We were indeed buried with him through baptism into death,

so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead

by the glory of the Father,

we too might live in newness of life. (Rom. 6:3-4)

We discussed the theological merits of this design, although in the end most of the committee members agreed that it would be too “creepy” for the congregation, especially since it was going to be positioned near the entry to the church (although younger generations might call it “metal,” as they say).

In the past, I have used this story in class as a funny way to explain an important point about the sacraments: each of them involves some form of participation in the life and ministry of Jesus. For example, the anointing of the sick is a participation in Jesus’ healing of the sick. Baptism, however, is particularly important because of the pivotal role it plays in the life of the Christian, as Paul makes clear in Romans 6.

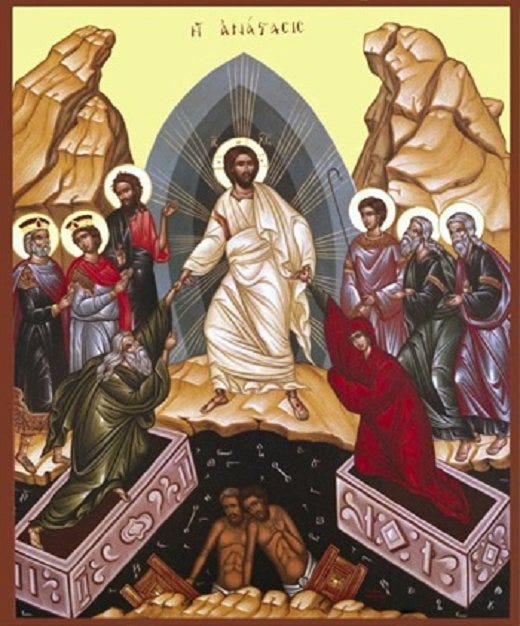

According to Paul, it is through being buried with Christ that we can experience the new life of the Resurrection. And it is through baptism that we experience that burial. Paul also claims that just as we participate in Christ’s death, eternal life is not something that we experience as an insolated individual; eternal life is life with Christ:

If, then, we have died with Christ,

we believe that we shall also live with him. (v. 8)

Paul adds, in a section not included in Sunday’s reading:

For if we have grown into union with him through a death like his, we shall also be united with him in the resurrection. (v. 5)

This reference to union with Christ, of course, calls to mind Paul’s discussion of our participation in the Body of Christ, particularly in the twelfth chapter of 1 Corinthians. It likewise calls to mind the sacrament of the Eucharist, the sacramental means of our ongoing participation in the life of Christ. Elsewhere in 1 Corinthians, Paul also speaks of the Eucharist as participation in Jesus’ mission:

The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ? The bread that we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? (1 Cor. 10:16)

And, as with baptism, he speaks of it in terms of union with Christ:

Because the loaf of bread is one, we, though many, are one body, for we all partake of the one loaf. (v. 17)

I think this idea that, through the sacraments, we participate in Christ’s life and mission is important because it suggests that the sacraments provide us a pattern of living such that our lives are a continuation of Christ’s ministry—of healing, reconciliation, liberation—in the world.

There is a bit of tension between the second reading and the Gospel reading for Sunday. Paul writes:

We know that Christ, raised from the dead, dies no more;

death no longer has power over him. (Rom. 6:9)

This suggests that, when we are baptized and therefore share in Christ’s death, we shall likewise die no more.

In Sunday’s Gospel, however, Jesus informs his disciples of the difficult road that lies ahead for his followers:

[W]hoever does not take up his cross

and follow after me is not worthy of me.

Whoever finds his life will lose it,

and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. (Mt. 10:38-39)

For Jesus, then, baptism does not seem to be a once-for-all dying, after which we “die no more”; rather, the entire Christian vocation, that only begins with baptism, is an ongoing process of losing one’s life, of taking up the cross.

I think this is simply a difference of emphasis. After all, the second reading closes with Paul saying:

As to his death, he died to sin once and for all;

as to his life, he lives for God.

Consequently, you too must think of yourselves as dead to sin

and living for God in Christ Jesus. (Rom. 6:10-11)

Although baptism completely washes away our sin, at baptism we have not fully “died to sin once and for all.” We continue to struggle with sin throughout our lives, as Paul attests elsewhere in Romans. Likewise, we continue to experience the death-dealing heaviness of the “powers” of this world. Although “death no longer has power over” Christ (v. 9), it still has some power over this world. As Paul explains in 1 Corinthians, “[Christ] must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. And the last enemy to be destroyed is death . . .” (1 Cor. 15:25-26). Our liberation in Christ, from sin and death, is a process that continues until the eschaton.

In his book The Politics of Jesus, the Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder argues that Christians err when they associate experiences such as illness or approaching death as “taking up one’s cross.” He claims that taking up the cross should be understood as a political act, the voluntary act of living out the Christian life, which invites the persecution of the world.

Although Yoder is right that we cannot ignore the political dimension of the Christian vocation and of what Jesus means by the cross, the presence of illness and death as “powers” from which Christ liberates us is too pervasive in the New Testament for us to dissociate illness and death from the cross. After all, in the second reading, Paul describes Jesus’ salvific work as overcoming the power of death: “death no longer has power over him” (v. 9). For Paul, “death” is not merely the end of the life cycle of a biological organism, but also a kind of structure pervading social life which lies behind the other oppressive structures we experience, what today we might call social sins.

If, as Yoder insists, the cross we must take up is the suffering we willingly accept as a consequence of our struggle against the “powers” of the world, then a Christian response to death—we endure the suffering of illness and death while boasting with Paul, “Death is swallowed up in victory. Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?”—can rightly be interpreted as taking up the cross, and even as a kind of political act. As many theologians have argued, it is hope in the Resurrection that ultimately gives us the strength to struggle against the death-dealing powers of this world.

Of Interest

On Thursday, the Supreme Court ruled in the case Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. the President and Fellows of Harvard College that colleges and universities cannot used racial preferences in their admissions policies. The decision is far-reaching, affecting all colleges and universities that receive federal funding, including Catholic institutions. The presidents of a number of Catholic universities, such as Seattle University and Fordham University, released statements lamenting the decision and renewing their commitment to promoting diversity on campus and addressing the ongoing impact of racism. At America, Dwayne David Paul, in a response to the Supreme Court decision, explores the concept of “affirmative action” and shows how it is supported by Catholic social teaching.

Earlier this week I offered a commentary on the Instrumentum Laboris, or working document, for the first session of the Synod on Synodality this October, which grew out of the synodal process that began in 2021 and that most recently resulted in seven continental documents reflected discussions from across the Catholic world. I linked to a few other commentaries, and now Anna Rowlands, the St. Hilda Chair in Catholic Social Thought and Practice at Durham University in the United Kingdom, and more importantly a member of the group responsible for both the European continental document and the Instrumentum Laboris, offers her own reflections on the document at America, particularly focusing on the surprising unity she found in the different Catholic voices from around the world. AMDG, a podcast sponsored by the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, also interviewed Dr. Rowlands about her experiences. (Also, I want to take this opportunity to take back my comments on the writing style of the IL…)